By Dan Hale, ATC Natural Resource and Land Stewardship Manager – Northeast

Species Movement on the A.T. Landscape

December 16, 2021

The Appalachian Trail (A.T.) is more than a hiking path for humans. The landscape surrounding the Trail is a superhighway for an amazing variety of species moving both locally and globally across the continent. The A.T. connects mountains and forests with rugged topography and ever-changing elevation, allowing wildlife to move into habitats that suits their needs. The complex and connected landscape of the A.T. enables the natural community to survive and move as temperatures rise and the weather becomes more extreme due to climate change.

In short, the A.T. and its surrounding landscape offer opportunities for all forms of life to adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

The A.T. Landscape contains and connects what scientists call “climate-change refugia,” defined as habitat that is likely to remain relatively resilient to future climate threats. Landscapes with diverse physical characteristics — such as steep mountains, deep valleys, and diverse geology — create a variety of microclimates that can provide suitable habitat for plants and animals despite a changing climate. An example of refugia is a north-facing valley shaded by mountains with a full canopy of trees and a cold-water stream. A place like this stays cool and provides water, helping animals to survive rising temperatures and potential drought caused by climate change.

Continuing the metaphor of a biodiversity superhighway, the A.T. Landscape will help enable species habitat ranges to shift as temperatures rise. Plants and animals are moving an average of 11 miles northward and 36 feet higher in elevation each decade in response to the changing climate. Climate change refugia can be considered a “slow lane” for species to survive and gradually shift their ranges while the broader landscape is more harshly impacted by climate change. Refugia may not serve a species’ needs forever, but by buffering the most extreme weather, they provide havens that allow species to survive during their climate-driven relocation.

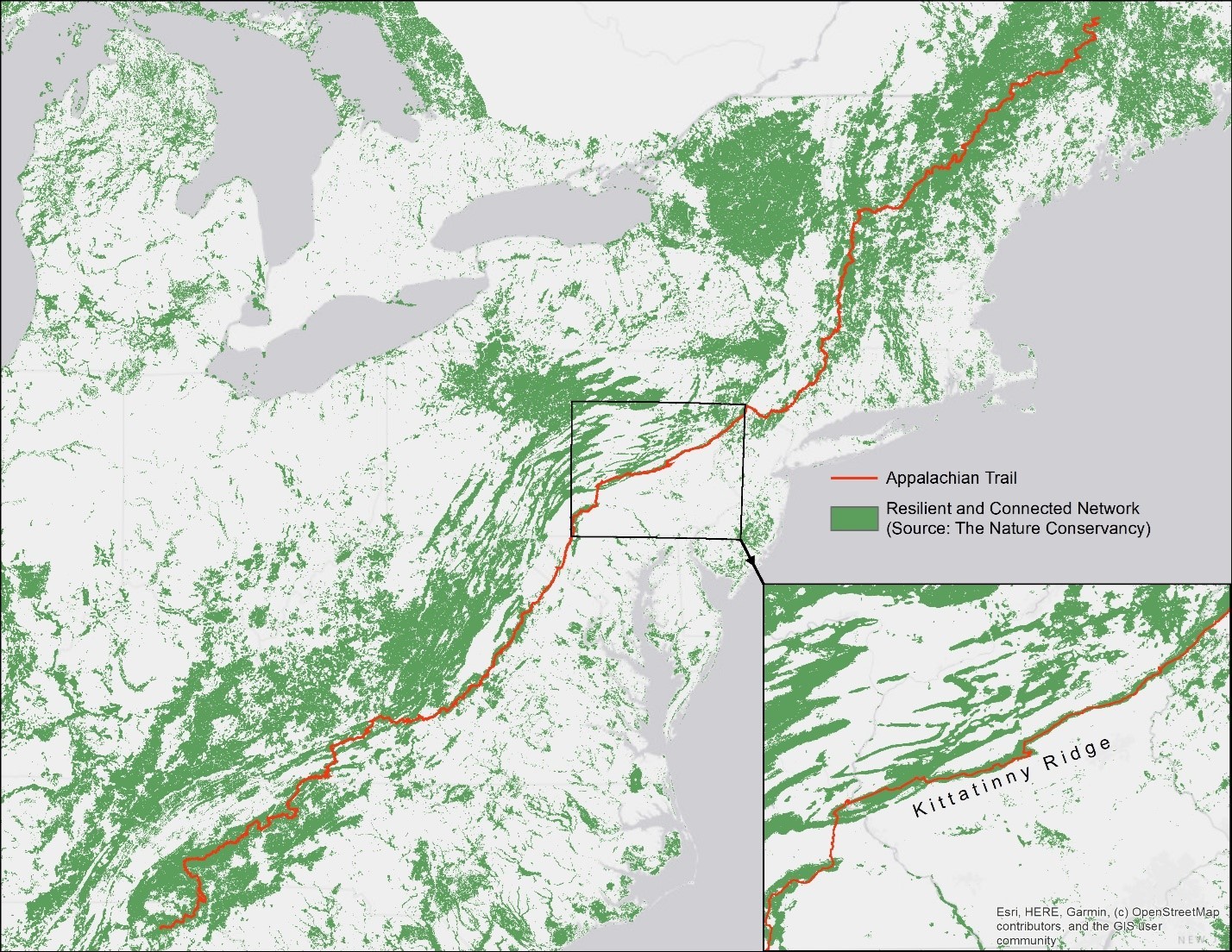

Map created by Dan Hale using data provided by The Nature Conservancy.

Our partners at The Nature Conservancy have mapped resilient lands and significant climate corridors across the continent, helping us to coordinate our conservation efforts by prioritizing and connecting refugia. Looking at this map (above), it is uncanny the way the A.T. is central to the resilient and connected landscapes of eastern North America. Of particular interest is the Kittatinny Ridge in Pennsylvania, which was identified as the most resilient landscape in the state for adapting to climate change.

As the climate warms, the A.T. Landscape not only harbors refuge for species but also, in its scale, offers opportunities for movement and survival. Below are three (of many) examples of wildlife that depends directly on climate-resilient A.T. Landscape.

Cerulean Warbler (Setophaga cerulea)

Male Cerulean Warbler (Image by Mdf, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Cerulean Warbler is a small bird with a short tail that is named for the sky blue of its head and back feathers. This bird forages for insects high in the treetops of mature forests and builds cup-shaped nests, sometimes over 100 feet above the ground. In winter, the Cerulean Warbler migrates to mountain forests in the Andes as far south as Bolivia, traveling over 3,000 miles each spring and fall. During this journey, this tiny bird flies 600 miles or more at a stretch between stopovers along the way. Sadly, Cerulean Warbler populations have declined 70 percent over the past 40 years due to habitat loss from deforestation in both their summer and winter habitats.

The A.T. Landscape contains important core habitat for the Cerulean Warbler, which needs interior forests far away from roads. One study conducted in the Kittatinny Ridge area of Pennsylvania counted far more Cerulean Warblers from sites on the A.T. and other hiking trails than from roadside sites. This study helped build the case for designating the Kittatinny Ridge as a Globally Important Bird Area in 2015. In addition to core habitat, forests at higher elevations provide cooler temperatures that can protect young birds in the nest from heat waves in the spring. Cerulean Warbler habitat is just one reason why the ATC and other organizations in the Appalachian Trail Landscape Partnership (ATLP) are working to conserve habitat in this area.

Moose (Alces alces)

A bull (male) moose (Image by Lisa Hupp/USFWS, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Moose are the largest animals in the A.T. Landscape, with an average adult standing six feet tall at the shoulder and weighing 1,000 pounds or more. Moose are adapted to cold climates, and in the northeast, they range from Canada as far south as Connecticut and New York. While moose populations have been expanding at the northern edge of their range, they face climate-related threats at the trailing southern edge of their range. Due to climate change, warmer days in the summer cause heat stress and shorter, milder winters allow winter ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) to thrive and attach to moose by the thousands, causing blood loss, hair loss, behavioral changes, and death. Winter ticks reduce moose reproductive rates and cause mortality for calves during their first winter. In the southern edge of their range, moose populations have steeply declined in recent years since their peak in the early 2000s.

Although climate change will cause significant shifts in moose habitat range, there is some evidence that moose can adapt and survive by using climate refugia. Research shows that on warm days, moose move to thermal refuges such as forested wetlands, shaded forests, and higher elevations. Moose at the southern edge of their range are the first populations to adapt to warmer temperatures, providing insight into the future of the species as the climate warms. Winter tick infestations are most common in high-density moose populations, so moose need space for their populations to spread out. These factors highlight the importance of protecting large areas of connected climate refugia in the A.T. Landscape.

Elk (Cervus elaphus manitobensis)

Elk in Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Image by Doug Brinkmeyer/ Great Smoky Mountains National Park, CC BY-SA 3.0).

A small but growing population of elk can be found in the A.T. Landscape in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina and Tennessee. The eastern elk subspecies that once roamed the Appalachian Mountains went extinct in the late 1800s due to hunting and habitat loss. However, twenty years ago, the National Park Service reintroduced 52 of the Manitoban elk subspecies in the Cataloochee area of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and this population has grown to an estimated 200 individuals.

As the population has grown, it has also spread to surrounding public and private lands, including a group near Max Patch on the A.T. Elk move across the landscape in search of habitat, food, and breeding opportunities, requiring large and connected undeveloped areas. Highways are a major threat, both limiting elk movement and killing them via automobile collisions.

A coalition of community members and conservation organizations called Safe Passage is making great progress toward improving wildlife connectivity in the Smoky Mountains region. They research, advocate, and raise funds for wildlife crossings on major roads, focusing on Interstate 40 in the Pigeon River Gorge. Construction is currently underway for a new bridge on I-40 at exit 7 in North Carolina, which passes over Cold Springs Creek and Harmon Den Road, a popular access point for Max Patch. This bridge is designed to direct wildlife under the highway through natural greenways along the creek. Nine-foot-tall fences will steer animals toward this wildlife crossing and cattle guards will keep them off the highway exit and entrance ramps.

Elsewhere in North Carolina, a land bridge design for the A.T. crossing of Route 143 at Stecoah Gap was approved this year, and construction is scheduled to begin in August 2022. The land bridge will be approximately 160 feet long, 220 feet wide, and 29-feet tall, filled with earth material and planted with trees and other vegetation. The A.T. will be rerouted across this land bridge, where hikers, elk, and other wildlife can safely pass over the busy highway.

The ATC helps facilitate the movement of species by stewarding the land we have conserved and working to conserve more land in the A.T. Landscape.

On lands managed by ATC, we work to protect the land from human impacts and provide habitat for plants and animals. We manage invasive species such as emerald ash borer beetles (Agrilus planipennis), garlic-mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), which kill or crowd out native species and are inedible or poor-quality food for wildlife. We prevent and mitigate encroachments on the land such as tree cutting, trash dumping, and motorized vehicle use. We manage for habitats that are uncommon on the landscape, such as forest openings, high-elevation red spruce forests (Picea rubens), inland Atlantic white cedar swamps (Chamaecyparis thyoides), and streams uninterrupted by human-built structures.

In the ATC’s strategic plan, we aim to protect an additional 100,000 acres of A.T. lands in the next three years, both by adding to the land we manage and by partnering with a network of conservation organizations throughout the region. Currently, ATC partners with more than 100 entities working on land conservation along the A.T. Landscape. We add capacity to partner organizations by providing funding through the Wild East Action Fund.

We are also working to influence government policies that would protect the A.T. Landscape and increase funding for conservation efforts. In particular, we strongly support the enactment of full fiscal year 2022 appropriations, which will fund the federal government. With the government currently operating on continuing resolutions (temporary government funding extending the previous year’s appropriations), there has been a delay in a much-needed increase in base operational funding for National Park System units (including for the Trail). The President’s Budget and the appropriations bills proposed in both chambers would fund this increase and provide vital funds for habitat restoration, combating invasive species, and protecting biodiversity. These necessary increases will not occur until Congress and the President approve a new appropriations law.

While the A.T. Landscape is a superhighway for species movement, it runs parallel to and is crossed by many human superhighways. The cities, suburbs, and highways of the east coast — referred to as the Northeast Megalopolis or Boston-Washington corridor — contain the largest area of urbanization in the country, with 17% of the US population living in 2% of its area. It is important to protect the A.T. Landscape from poorly planned urban expansion, not just for plants and animals, but also to provide open space and outdoor recreation opportunities for all the people living nearby. The efforts we invest in protecting this landscape will have lasting effects on generations of humans and wildlife.

Discover More

Official Blog

The A.T. and Climate Change: Reviewing the Basics

As we continue our series on climate change and its effects on the Appalachian Trail, it is important to lay the groundwork for several key topics.

Official Blog

Climate Resiliency and the A.T.

Protecting and expanding climate-resilient forests along the Appalachian Trail is vital to ensuring their long-term survival.

Official Blog

A Climate-Resilient A.T. Depends on Effective Federal Policy

Engaging in the creation of federal policy to protect the lands we love is one of the most effective tools to help mitigate the impacts of climate change on the Appalachian Trail.