by Michael Garrigan

Creases and Contours

June 3, 2022

How Paper Maps Teach Us the Language of Place

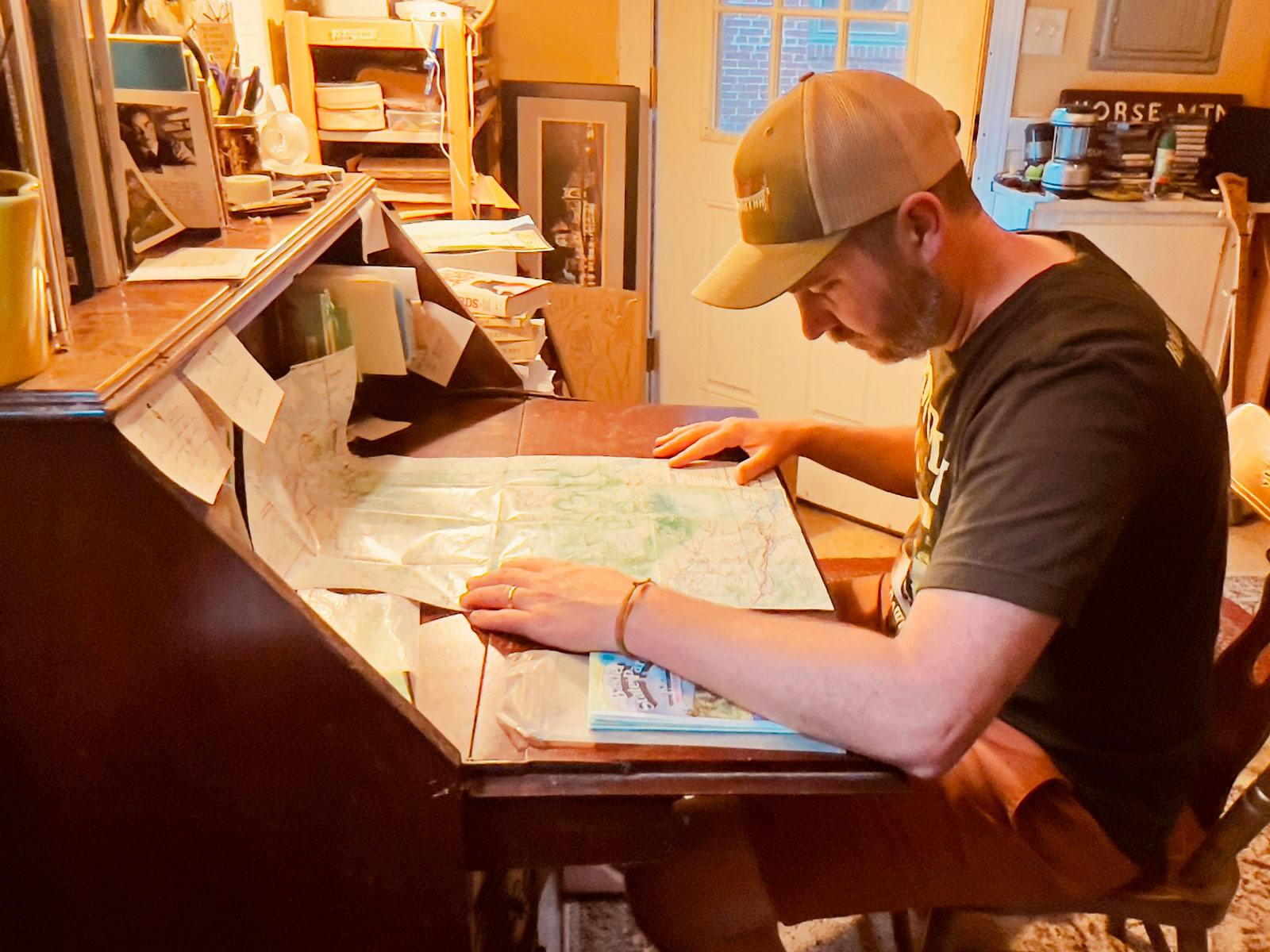

Whenever I get stuck and feel like I’m writing the same thing over and over, I look up from my desk and stare at a large wall-sized map of Pennsylvania that has every blue line in the state and the major watershed boundaries highlighted. I let my eyes wander and rest on any line and am immediately taken into some mysterious ravine casting into a pool for brook trout, scrambling through a thick rhododendron patch, or hiking along a deer path following water downstream, tributary to tributary, until I reach the Chesapeake, the Susquehanna, or the Allegheny. For a few minutes, while gazing at that map, I am lost in wonder and mystery that pulls me out of my inertia and back into the world of creation.

“Whether I’m feeling lost or wanting something to look forward to, tangible paper maps are what I go to when I need to find my way.”

Inevitably, sometime in late winter when the ground is frozen and the days just begin to reach a little further a little longer with a little more light, I dig into one of two milk crates full of random maps I’ve collected over the years and begin daydreaming and sketching my summer trips. I spread them out on the floor of my writing room, finding trailheads and planning where I’d camp and fish, which ridges I’d like to traverse, which peaks I’d like to see. It’s a deliberate act of survival — a combination of wishful thinking, careful planning, and wandering imagination that helps me get through cold, blustery winter days. Whether I’m feeling lost or wanting something to look forward to, tangible paper maps are what I go to when I need to find my way. Each map speaks a singular language, a vernacular sketch of a place that, when studied, gives us the shape and sound of a landscape.

The first thing I did after getting hired for the Baxter State Park trail crew right after college was to buy one of their maps. I’d sit at my desk in Pennsylvania and trace the Appalachian Trail (A.T.) as it left the 100-Mile Wilderness and entered the Park for its last ten miles through Katahdin Stream campground and up the Hunt Trail, through Thoreau Springs and up the final pitch to Baxter Peak. Studying the topographical lines of Katahdin, imagining myself walking across the Knife’s Edge and, doubling back, climbing down through Thoreau Springs after the summit. Though I had never been to Maine or climbed a mountain before, that map helped prepare me for that move. I had never done trail work or lived in a rustic cabin in the middle of a vast wilderness; yet I already felt close to that place, like I could understand how to read its landscape. When I finally got to Baxter State Park and climbed Katahdin for the first time, I felt like I was prepared and not completely helpless. There was something familiar about the rhythm of the trail, like I had seen and felt its contours.

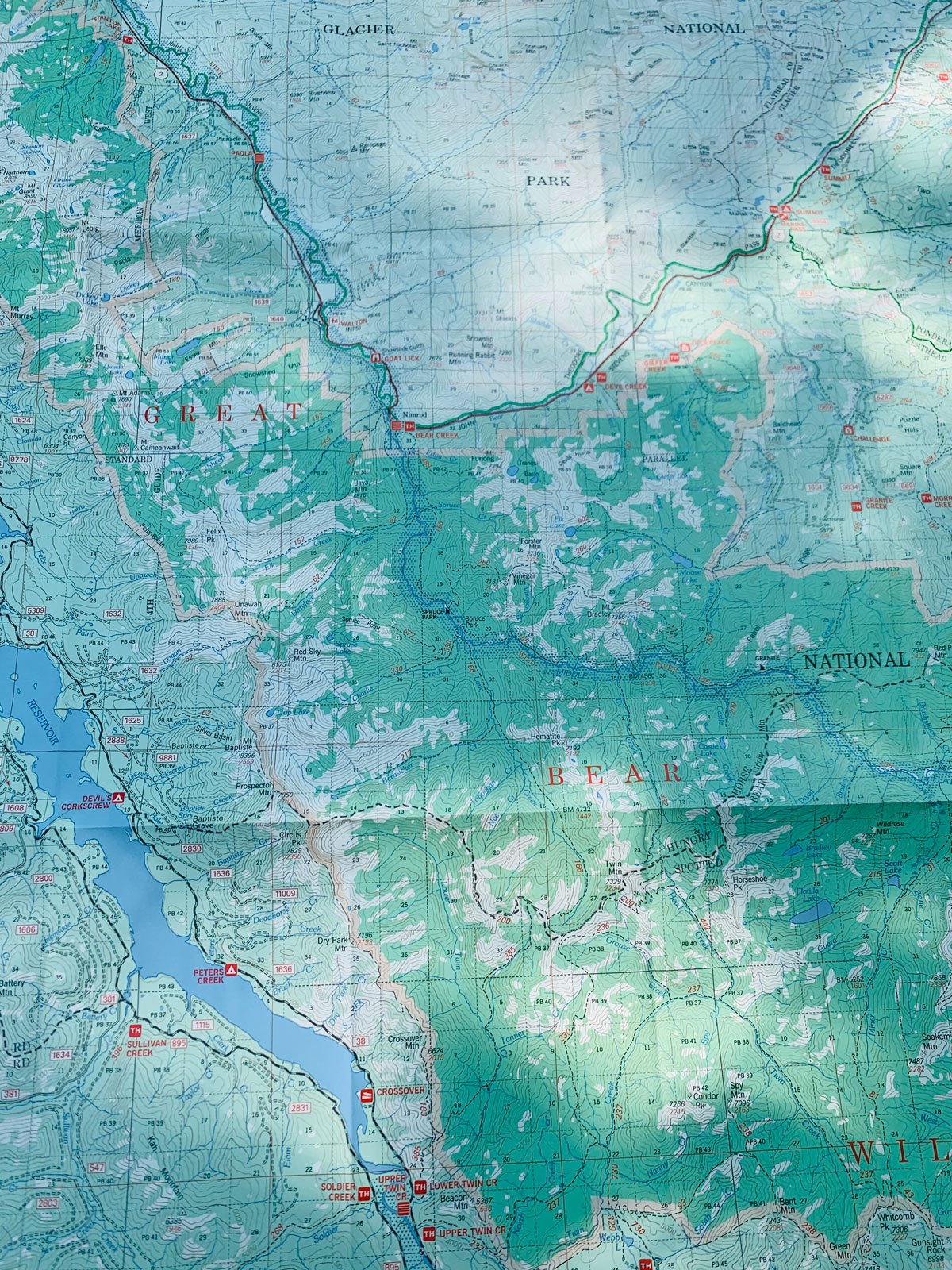

“That map [of Bob Marshall Wilderness] was my first way of communicating with that wilderness. It taught me its language — the syntax of its ridges, the cadence of its river bends, the inflection of its ledges, and the tone of its peaks.”

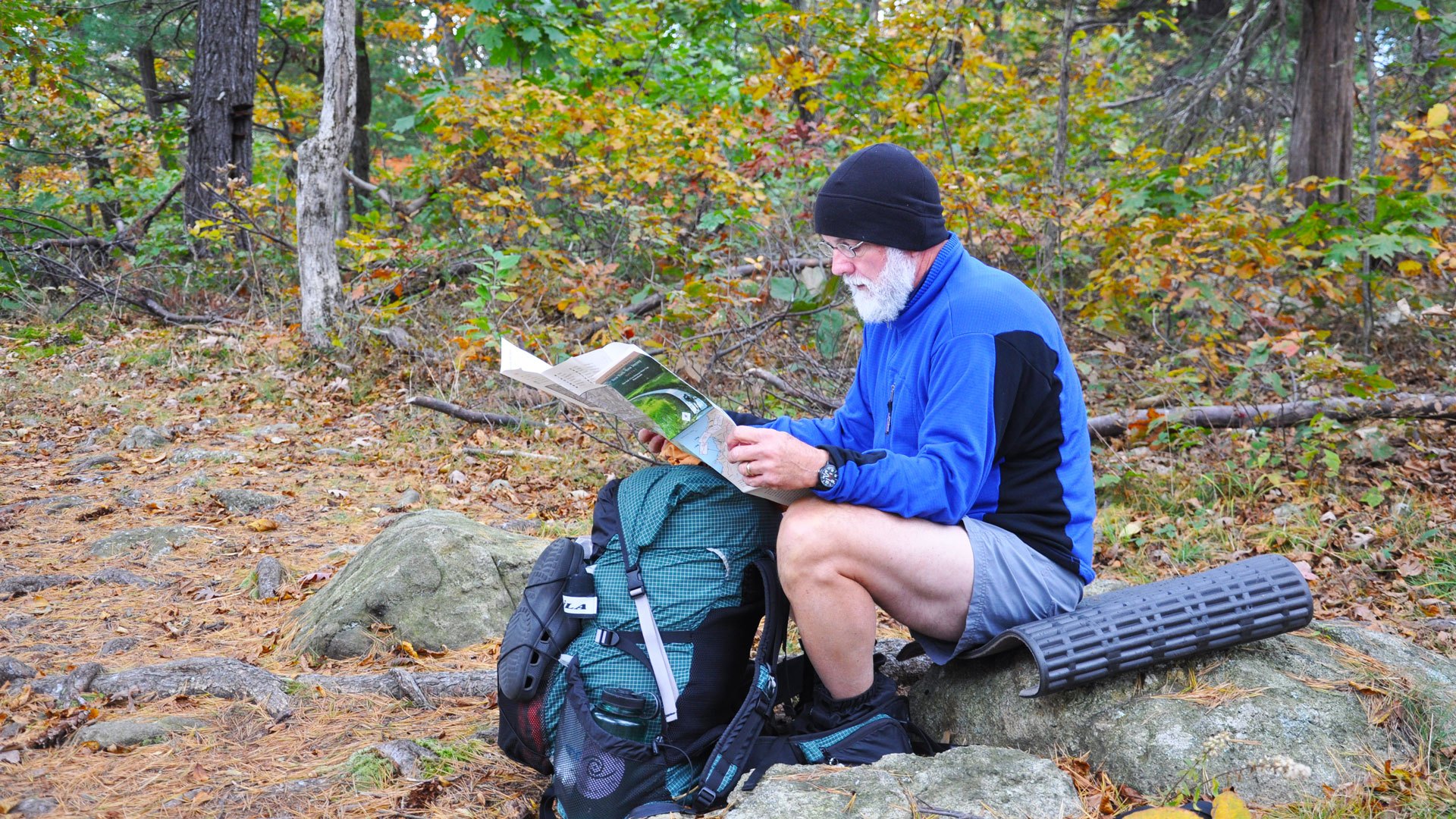

That map also came with me every time I left the cabin. It’s incredibly important to be fully prepared when out on the trail, and while a GPS unit is an essential part of every pack (especially one that can connect you with Wilderness Rescue in the backcountry), I always made sure I had my paper map in a Ziploc bag somewhere in my pack. It would never run out of batteries and would provide a wider perspective of where I was and where I wanted to go. I could see more and understand the wilderness I was in and hear its full song, not just the one verse my GPS unit could show me clearly. With that map, I was able to orient myself in the linguistical deviations of that landscape. It’s easy for us to get lost in a screen and to habitually check a GPS unit to constantly coordinate where we are and where we’re headed. Knowledge is not a bad thing, but sometimes a paper map tucked into a pack provides a more deliberate, less distracting way to get one’s bearings.

Each map speaks a singular language, a vernacular sketch of a place that, when studied, gives us the shape and sound of a landscape.

Maps, much like the hikes we plan with them, change as they get used and are experienced. Like any language, maps hold history and story. The early versions of A.T. maps had Mount Oglethorpe as the southern terminus, whereas the current maps note its home on Springer Mountain. The newest maps will be the longest, with the Trail growing to 2194.3 miles in 2022. Older trails will have straighter, steeper paths up the Appalachian Mountains, whereas newer trails will have more switchbacks — an evolution of our understanding of how trails should be built, and how that understanding was informed by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) and the Trail Maintaining Clubs to help protect the Trail itself and improve the A.T. hiking experience. Trails get rerouted, trails get built. Rivers oxbow, boundaries change. Lean-tos are added, springs are found. Maps are never complete, but rather snapshots in time, never in complete stasis. They change and respond, sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly. Sections are lengthened or shortened depending on the techniques used to ensure the trail is built sustainably. Each version of a map is a distinct mark of the trail’s character. Histories aren’t overlaid or lost with maps, and each version adds to its etymology and persona.

The original map proposing the route of the A.T. from Benton MacKaye’s groundbreaking 1921 article, “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning.”

The first A.T. maps tie back to the original idea by Benton MacKaye when, in 1921, he called for the construction of the trail. With that proposal, the coordination of the ATC (then the Appalachian Trail Conference), and the continuous work and collaboration of many local trail associations, both the literal map and a shared map that millions are able to traverse each year were created. Each person who takes a step on the A.T. is using a map created and cared for by thousands of volunteer hours, but they are also, in some ways, creating their own map, adding their own syllables to a language that is constantly being spoken and developed. The A.T. is a shared map that each person adds to, uses, and revises. The literal map is simply a guidepost that in turn creates a personal map of that time on the trail filled with physical exaltations and struggles, sweat and bug bites.

Humans aren’t the only ones who map the landscape, and outdoor recreation isn’t the only thing that maps are used for. Animals have their own maps that are living, breathing documents of their experiences and lives along the Trail. These maps are made apparent by their movements and by tracking done by conservation groups. By mapping which animals use the area surrounding the A.T., we are better equipped to be stewards of that landscape and can work to better protect the biodiversity of the Appalachian Mountains. For example, land bridges have been planned for the A.T. throughout the Smoky Mountains region in order to enable animals such as elk to cross busy roads safely. The Cerulean Warbler uses the protected lands and mature forests along the Kittatinny Ridge in Pennsylvania to build nests and forage for insects. This is critical habitat for this migrating bird that is now further protected as a Globally Important Bird Area because of the mapping done by the ATC, Appalachian Trail Landscape Partnership (ATLP), and The Nature Conservancy. Maps that catalog and inventory a landscape’s ecosystem help ensure protection of plants and animals and support biodiversity along the trail and that future maps represent the intricate ecosystems the A.T. travels through.

“It’s easy for us to get lost in a screen and to habitually check a GPS unit to constantly coordinate where we are and where we’re headed… sometimes a paper map tucked into a pack provides a more deliberate, less distracting way to get one’s bearings.”

Maps hold the story of our personal experience with a place and how we learned to communicate with it. Notations along trails, circles around streams, arrows to peaks, highlights on tributaries, three lines under trailheads — each mark is a deliberate, personal connection to that place. Then there are the inevitable coffee stains from early morning trip preparation and dirt smears from trailside checks and watermarks from freak rainstorms and small tears from excitement. Anticipation, mystery, wonder, contemplation, worry, comfort — all the emotions that build a language and experience are documented and held on a map.

Each crease of a map tells a story, and to hold and read a map is to learn the language of a place. Each crease adds to the vermiculating contours of the landscapes we explore. Each highlight or notation is a daydream, a reminder, a place to return to. Maps help us become better translators, stronger stewards, and smarter explorers of this world. They are reflections of what we value: wild and protected places to look at and visit again and again, knowing at any moment we can venture into a landscape and become part of its ecosystem.

Michael Garrigan writes, teaches, and hikes along the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. He is the author of Robbing the Pillars and his next poetry collection — River, Amen — will be published this fall. He was the 2021 Artist in Residence for The Bob Marshall Wilderness Area and you can read more of his work at www.mgarrigan.com.

Michael Garrigan writes, teaches, and hikes along the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. He is the author of Robbing the Pillars and his next poetry collection — River, Amen — will be published this fall. He was the 2021 Artist in Residence for The Bob Marshall Wilderness Area and you can read more of his work at www.mgarrigan.com.Discover More

Plan and Prepare

Hiker Resource Library

A collection of resources for hikers to stay safe, healthy, and responsible on the Appalachian Trail.

Know Before You Go

Hiker Preparation Series

Before heading out to the Appalachian Trail for your long-distance hike, check out our hiker preparation series for tips and checklists on how to have a safe and enjoyable A.T. experience.

ATC's Official Blog

A.T. Footpath

Learn more about ATC's work and the community of dreamers and doers protecting and celebrating the Appalachian Trail.