By Mills Kelly

Why the Length of the Appalachian Trail Is Always Changing

May 11, 2023

Sometimes I feel bad for the tall wooden sign placed just north of the Toms Run Shelter south of Pinegrove Furnace State Park and the AT Museum. That sign proudly proclaims itself the trail’s halfway point.

But it isn’t.

I feel equally sorry for the big bronze plaque on top of Center Point Knob, just a little north of the Museum. It also proclaims itself the halfway point of the Trail.

But it isn’t.

I wonder, do those markers feel bad about themselves, given that they so badly mislead Appalachian Trail thru-hikers anxious to reach the halfway point of their long journey?

About a decade ago, a trail club volunteer did make a small, laminated sign that he used to move to the actual halfway point each year, but even that practice seems to have come to an end.

If the Appalachian Trail would stay the same length from year to year, someone could put up an accurate sign, one that is actually located at the Trail’s halfway point. Alas, that’s not going to happen anytime soon.

Mileage marker at Center Point Knob, Pennsylvania. Photo by Mills Kelly

The Appalachian Trail is constantly changing, getting a little longer one year, a bit shorter in a different year. For those keeping track, in 2023 the Trail is almost 150 miles longer than it was in 1937 when the Trail’s managers first declared it complete.

But why is the length so changeable?

From Roads to Forests

The first “complete” version of the Trail arrived in the summer of 1937, sixteen years after Benton MacKaye first proposed the creation of what he called “an Appalachian Trail.” That first version was 2,050 miles long from the summit of Mount Oglethorpe in Georgia to the summit of Katahdin in Maine.

But even as the Trail’s managers were bathing in the satisfaction of having completed a hiking trail that spanned 14 states and more than 2,000 miles, legendary ATC Chairman Myron Avery admonished them that their work would never end. In his report to the assembled Conference delegates, Avery said, “To say that the Trail is completed would be an entire misnomer… The Appalachian Trail will always be unfinished.”

The passing decades have proven just how right he was.

The Appalachian Trail of 1937 and the A.T. of 2023 are two very different trails. And not just because today’s Trail is so much longer. That original version of the Trail included hundreds and hundreds of miles of road walking and hundreds more of plodding across cow pastures and farm fields. Long sections of the Trail had been heavily logged, and hikers had to pick their way north or south by spotting cairns set up by local trail clubs. Perhaps most concerning of all was the fact that most of the Trail was on private land, held together by tenuous easement agreements with landowners who could revoke their permission for hikers to cross their property with minimal notice.

At that 1937 meeting, Avery admonished his colleagues to get to work doing two things – building a chain of shelters from one end of the Trail to the other and devoting maximum energy to improving and protecting the Trail’s route.

“Improving the route” meant many things to many people, but everyone could agree that the top priority was getting as much of the Trail as possible off roads and into the forest. Since that meant making more agreements with those who owned the forests, local trail club volunteers spent countless hours building relationships with their landowning neighbors.

From Private to Public Lands

Wherever possible, the ATC and the clubs did their best to route the Trail through the expanding network of public lands like national forests and state parks. Doing so often meant moving the Trail significant distances to get it onto public lands where it would have a more secure existence.

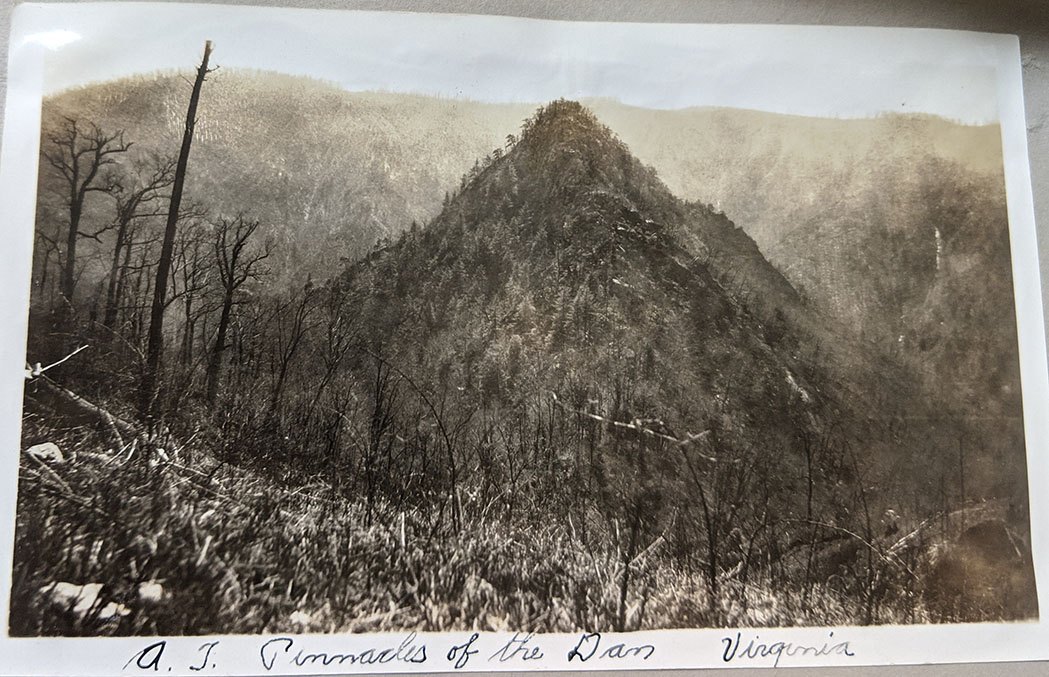

For instance, as I detail in my book Virginia’s Lost Appalachian Trail, a full 300 miles of the Trail in Southwest Virginia shifted 50 miles west in 1952 to move the route into the Jefferson National Forest and away from roads and private land. That move cost hikers access to the Pinnacles of Dan, described by hikers as one of the most beautiful and most difficult parts of the entire Trail, but the Trail’s managers were convinced that having the Trail on public land was well worth the sacrifice of some scenic sections.

Photo of the Pinnacles of Dan from Myron Avery’s scrapbook (1932). Photo courtesy of ATC Archives

Sometimes the goal of Trail protection meant giving up mileage instead of adding it. In the late 1950s, the Georgia Trail Club and the ATC moved the southern terminus of the trail 37 miles north from Mount Oglethorpe to Springer Mountain. The original terminus was on private land, and a real estate developer was putting up vacation homes on the mountain as fast as possible. Plus, chicken farms on either side of the Trail between Oglethorpe and Springer forced hikers to walk through a horrible stench. Almost no one complained when those 37 miles of Trail vanished.

Maximizing Beauty

In addition to getting the Trail off roads and onto protected land, the ATC and the clubs wanted to make the route as beautiful and scenic as possible, while keeping the hikes challenging enough to be interesting — but not so challenging that hikers couldn’t manage them. Trail planners were always looking for better ways to get through the mountains while maximizing the beauty of any given section.

After the passage of the National Scenic Trails Act in 1968, property owners who feared the loss of their land began canceling their easements for the A.T. Many sections of the Trail were diverted back onto roads.

Perhaps the most famous instance of this phenomenon happened in Virginia. Landowners on Catawba and Tinker Mountain outside of Roanoke closed the Trail there in 1975, denying hikers access to McAfee Knob and Tinker Cliffs for several years. During that time the Trail got a little longer, because hikers had to cross the valley west of McAfee, climb up onto North Mountain, hike north until they passed Tinker Cliffs, then cut back across the valley to the present route of the Trail.

Another famous relocation in Virginia was the section between Highway 50 and Route 7 near Harpers Ferry. Following the passage of the Trails Act, a number of landowners on Mount Weather canceled their easements, forcing the Trail onto Route 601 for 15 miles of really boring road walking. In the 1980s, enough land on the shoulders of the mountain was available to move the trail back into the forest — and what would eventually become the Roller Coaster.

Route changes happened up and down the trail from 1937 onward, including this past year – from the Carlisle Valley in Pennsylvania to the creation of the route through the 100 Mile Wilderness in Maine. Through the years, the ATC and Trail Clubs have worked to overcome obstacles to the Trail’s existence and re-routes are one of the most visible elements of this work. Each change has made the Trail a little longer or a little shorter and has meant that the trail one hikes today is not the trail someone else hiked a decade ago.

As Myron Avery said about the Trail way back in 1937, “As long as the project exists, there will be ever present, in increasing seriousness, the problems of maintenance and of developing a greater utilization of the Trail’s attractions.”

And those signs in Pennsylvania will always be wrong.

Historian Mills Kelly is a professor at George Mason University and the author of Virginia’s Lost Appalachian Trail (The History Press, 2023). He is also the host of the Green Tunnel Podcast, which explores the history of the Appalachian Trail.