BY LEANNA JOYNER, ATC SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIPS AND TRAIL OPERATIONS

Post-Civil War Harpers Ferry and African American History

February 24, 2023

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, is perhaps best known as the site of John Brown’s Raid, a pivotal moment in U.S. history that ultimately helped spark the American Civil War. Yet after the war ended, Harpers Ferry took on a very different role, particularly for African Americans as they pursued better lives, higher education, and equality under the law in post-slavery America. As you follow the Appalachian Trail through Harpers Ferry, you will pass by multiple landmarks in African American history.

Storer College

The year the Civil War ended and three years after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, a primary school was established in Harpers Ferry to provide an education to formerly enslaved people. Some people closest to the development of the school, members of the Freewill Baptist Church, questioned the likelihood of its success, likening it to “a railroad to the moon.” Students and teachers were discouraged by angry and often violent encounters with local community members, but the school and its student enrollment grew.

The primary school that started in one building, the Lockwood House, grew to 2,500 students by 1867. In October of that year, the school’s founder, the Rev. Dr. Nathan Cook Brackett, received funding from philanthropist John Storer of Maine. The $10,000 gift from Storer required that the school be open to anyone, regardless of gender, race, or religious belief, and the institution became known as the Storer Normal School. The funds and the formal transfer of the Lockwood House and three other former armory buildings from the federal government to the school in 1869 allowed the school to offer greater educational opportunities to even more students.

Appalachian Trail visitors taking the side trail to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy Headquarters and Visitor Center will pass through the Storer College campus, which is now overseen by the National Park Service. Photo: National Park Service / Claire Hassler

The Storer campus on Camp Hill in Harpers Ferry was chartered by the state of West Virginia in 1869, and the first class graduated in 1872. These graduates were trained so that they could teach students at other freedmen schools. Storer College was among the first institutions in the post-war United States to educate African Americans. Its board of trustees included reformer and orator Frederick Douglass, who gave a speech at the college in May 1881 in which he extolled John Brown’s virtues, sacrifices, and contributions to the advancement of Blacks as free citizens of the nation.

The rich history of Brown’s deeds in Harpers Ferry brought the Niagara Movement, a precursor to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, to Harpers Ferry for a conference in 1906 at Storer College (see below). The college lost funding from federal and state sources following the desegregation of schools with the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, and it closed in 1955.

Learn more about Storer College at www.nps.gov/places/storer-college.htm.

“Either the United States will destroy ignorance or ignorance will destroy the United States.”

-W.E.B. Du Bois

The Niagara Movement

The legacy of John Brown’s struggle for human equality brought the Niagara Movement to Harpers Ferry in 1906 for its second conference. Held August 15-19, the program featured speakers, assessments of civic and political situations, and discussions on reforms related to crime, health, education, and the media. Nearly 100 attendees convened at the Storer College campus. They walked from the campus to the Murphy Farm, where John Brown’s “fort” had been located since 1894, in a “silent procession” to honor the sacrifice Brown made in the name of liberty of all.

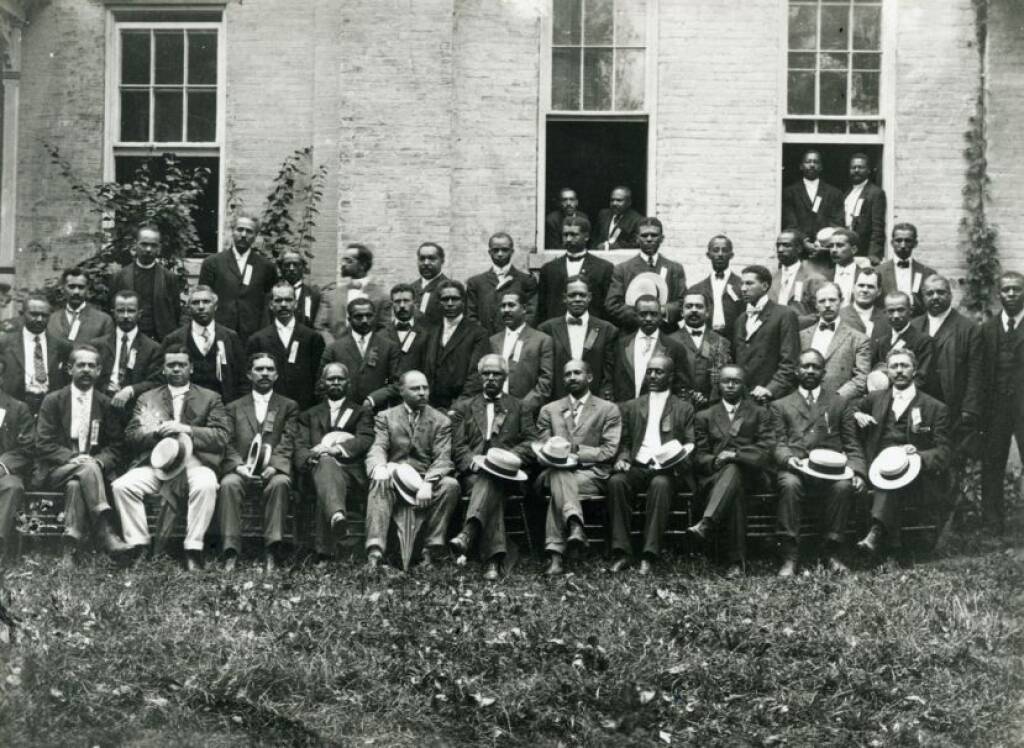

Niagara Conference attendees pose in front of Anthony Hall — now known as Wirth Hall — at the conclusion of the 1906 Niagara Conference on the campus of Storer College in Harpers Ferry. The building is on the A.T. side trail. (Historic Photo Collection, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park)

At the conclusion of the conference, W.E.B. Du Bois read a resolution that summed up the desires of the movement’s constituents and served as a message to the nation on social inequalities:

In detail, our demands are clear and unequivocal. First, we would vote; with the right to vote goes everything, freedom, manhood, the honor of our wives, the chastity of our daughters, the right to work, and the chance to rise and let no man listen to those who deny this.

We want full manhood suffrage and we want it now, henceforth and forever.

Second. We want discrimination in public accommodation to cease. Separation in railway and street cars, based simply on race mid color, is un-American, undemocratic and silly. We protest against all such discrimination.

Third. We claim the right of freemen to walk, talk and be with who we wish to be with us. No man has a right to choose another man’s friends and to attempt to do so is an impudent interference with the most fundamental human privilege.

Fourth. We want the law enforced against the rich as well as the poor, against Capitalist as well as Laborer; against white as well as black. We are not more lawless than the white race, we are often more arrested, convicted and mobbed. We want justice even for criminals and outlaws. We want the Constitution of the country enforced. We want Congress to take charge of the Congressional elections. We want the Fourteenth Amendment carried out to the letter and every State disenfranchised in Congress which attempts to disenfranchise its rightful voters. We want the Fifteenth Amendment enforced and no State allowed to have its franchise on color.

Fifth. We want our children educated. The school system in the country districts of the South is a disgrace and in few towns and cities are the Negro schools what they ought to be. We want the national government to step in and wipe out illiteracy in the South. Either the United States will destroy ignorance or ignorance will destroy the United States.

The first meeting of the Niagara Movement had been along the Niagara River in Ontario and hosted twenty-nine men from fourteen states. Its members met again in 1907, 1908, and 1909 in Massachusetts, Ohio, and New Jersey, respectively, but by 1911 the organization had been dissolved. Niagara Movement founder Du Bois urged its members to join the NAACP to continue to advocate for civil rights.

Learn more about the Niagara Movement at www.nps.gov/hafe/learn/historyculture/the-niagara-movement.htm.

About W.E.B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois has a dual connection to places on or near the Appalachian Trail-Harpers Ferry in West Virginia and Great Barrington in Massachusetts.

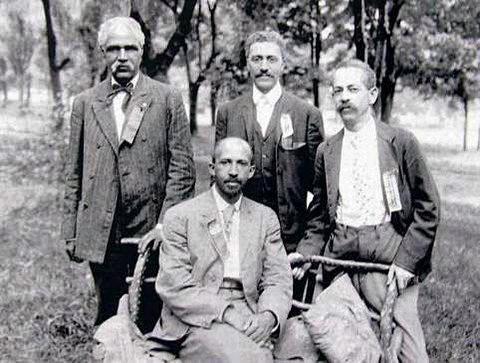

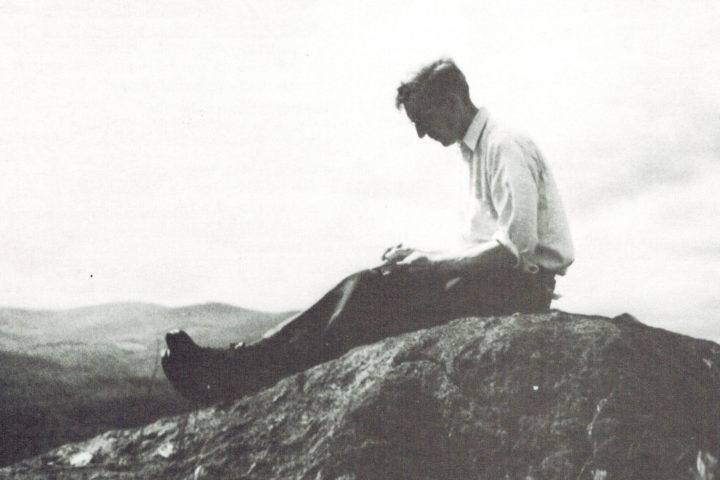

Niagara Movement members at Harpers Ferry in 1906. W.E.B. Du Bois is seated in front. (Historic Photo Collection, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park)

Most significantly, W.E.B. Du Bois was a “principal architect in the civil rights movement of the United States;227 and he brought the founding organization for civil rights, the Niagara Movement, to Harpers Ferry in 1906 for its second conference when he was 38 years old. The Niagara Movement was the organization that preceded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in its work for equal rights.

As a scholar, Du Bois wrote sixteen books, including one published in 1909 on John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry and others particularly related to race relations and sociology. He was the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard, and he taught at schools and universities in Georgia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York.

Du Bois was born in February 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, roughly four miles from the current Appalachian Trail, which meanders above the eastern shore of the Housatonic River there. His parents had rented a small rear dwelling on Church Street owned by a formerly enslaved person from South Carolina. He described his hometown this way:

I was born by a golden river and in the shadow of two great hills. My birth place was Great Barrington, a little town in western Massachusetts in the valley of the Housatonic, flanked by the Berkshire Hills.

He was raised in different houses in Great Barrington. One was on Church Street, one was above the stables on the Increase Sumner estate, and another was his grandfather Othello Burghardt’s homestead on current Mass. 42/23. Neither of the homes remain, although plaques dedicated to his birthplace and childhood home can be seen at or near both.

“Slavery is a state of war.”

-John Brown

John Brown’s “Fort”

Miraculously, John Brown’s “fort” was not burned, destroyed by cannon fire or otherwise demolished during the years of fighting in Harpers Ferry over the course of the war. Left intact, it was a relic of Brown’s failed 1859 mission that has, throughout history, served as a spectacle, a symbol of sacrifice, and a centerpiece of power. Indeed, for some time after the war, “John Brown’s Fort” was painted above its doors, and it served as a tourist attraction in the otherwise rundown town.

John Brown’s Fort rests just feet from the A.T., providing thousands with an opportunity to explore this small-but-historically-significant building.

David Gilbert writes on the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park Web site of the curious relocating of the structure this way lure this way:

In 1891, the fort was sold, dismantled and transported to Chicago where it was displayed a short distance from The World’s Columbian Exposition. The building, attracting only 11 visitors in ten days, was closed, dismantled again and left on a vacant lot.

In 1894, Washington, D.C. journalist Kate Field, who had a keen interest in preserving memorabilia of John Brown, spearheaded a campaign to return the fort to Harpers Ferry.

Local resident Alexander Murphy made five acres available to Miss Field for the cost of $1, and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad offered to ship the disassembled fort to Harpers Ferry free of charge. In 1895, John Brown’s Fort was rebuilt on the Murphy Farm about three miles outside of town on a bluff overlooking the Shenandoah River.

In 1903, Storer College began their own fundraising drive to acquire the structure. In 1909, on the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of John Brown’s Raid, the building was purchased and moved to the Storer College campus on Camp Hill in Harpers Ferry.

Acquired by the National Park Service in 1960, the building was moved back to the Lower Town in 1968. Because the fort’s original site was covered with a railroad embankment in 1894, the building was placed about 150 feet east of its original location.

Should funds ever become available to dig out the embankments that cover the old armory sites, the park hopes to relocate the engine house to its original location one day.

Learn more about John Brown’s Raid at www.nps.gov/articles/john-browns-raid.htm.

This article is excerpted from Hiking through History: Civil War Sites on the Appalachian Trail by Leanna Joyner, Senior Director of Partnerships and Trail Operations for the ATC. Purchase your own copy from our partners at Mountaineers Books and help support our work to protect, maintain, and advocate for the A.T.

Discover More

Official Blog

The Community of Formerly Enslaved People at Brown Mountain Creek

Located on the Appalachian Trail in Virginia, Brown Mountain Creek shows us a history of both slavery and freedom for African Americans after the Civil War.

A History of Trail Building

ATC History

Just like the Appalachian Trail, our history is long. But throughout the years, the heart of our organization has remained the same: to protect and manage over 2,190 miles of the A.T. footpath and its surrounding landscapes.

A Century of Inspiration

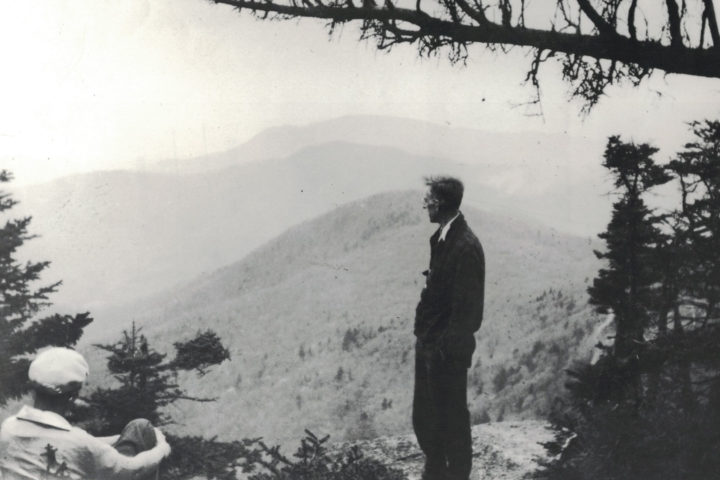

Benton MacKaye: Celebrating a Vision

2021 marks the 100-year anniversary of the publication of Benton MacKaye’s groundbreaking article proposing the Appalachian Trail. Even after a century, MacKaye’s original vision continues to inspire and guide us.