by Robert "Bob" Proudman

Tips on Tons: Tools and Techniques – Simple Machines and Mechanical Advantage (Part 2 of 2)

Note: For advice on preliminary work planning, refer to Part 1 of this series from the November 1984 issue of The Register.

(Part 2 of 2)

Simple Machines and Mechanical Advantage

All hand tools for trail work (and other human endeavors) consist of one or more “simple machines.” There are six simple machines: the lever, the wheel and axle, the pulley, the inclined plane, the wedge, and the screw.

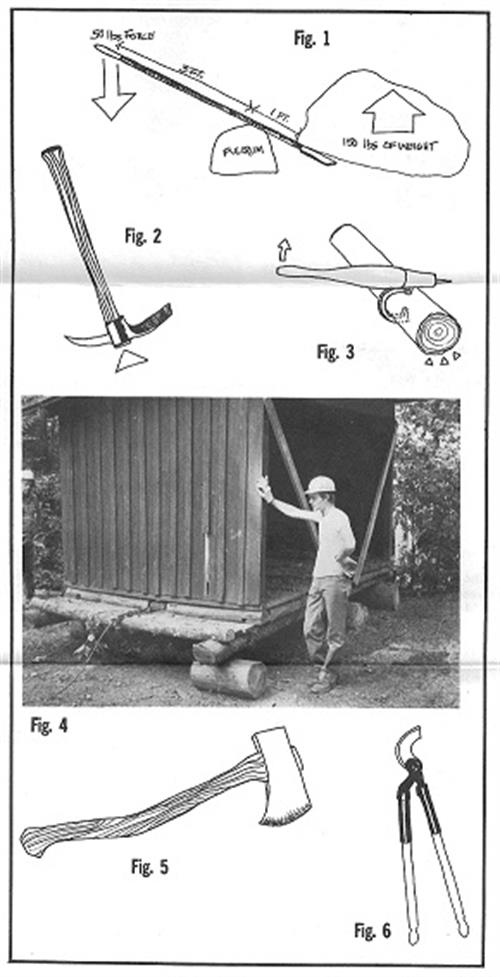

The best known and most commonly used simple machine is the lever, a rigid bar that pivots on a fixed axis called a “fulcrum.” The most frequently used lever in trail work is the crowbar. When using the crowbar the trail worker intuitively understands “mechanical advantage,” which is the multiplication of force to perform useful work. (See Fig. 1)

The ratio of force applied to effective weight lifted is 3:1 or a mechanical advantage of three. The ratio of mechanical advantage is always proportional to the distance between the fulcrum and the work force, and the fulcrum and the target weight.

As the fulcrum (usually a rock) is moved closer to the target weight, the ratio increases and the amount of weight the worker can lift increases, although obviously for proportionally shorter distances. As a result, the weakest member of a trail club can, with only 25 pounds of force, lift a 500-pound rock approximately 2 inches. With a succession of lifts, fulcrum movements, and propping up the weight with rocks, tremendous weight can be moved over significant distances. With practice and patience, the trail worker will achieve surprising results.

Other Simple Machines in Trail Work

Fig. 2 The Mattock is a bent lever. The most familiar bent lever is probably the claw hammer.

Fig. 3 The Pee Vee is a lever used for rolling large logs.

Fig. 4 Log rollers use “the wheel” to reduce friction and achieve mechanical advantage.

Fig. 5 Mechanical advantage of the axe and all blade cutting tools increases with the sharpness of the edge. That is, the axe user is more effective the sharper his tool.

Fig. 6 The pruner is a double lever and wedge.

The inclined plane is used to lift heavy logs for shelter construction or crib construction for bridges.

Creative Trail Club Solutions

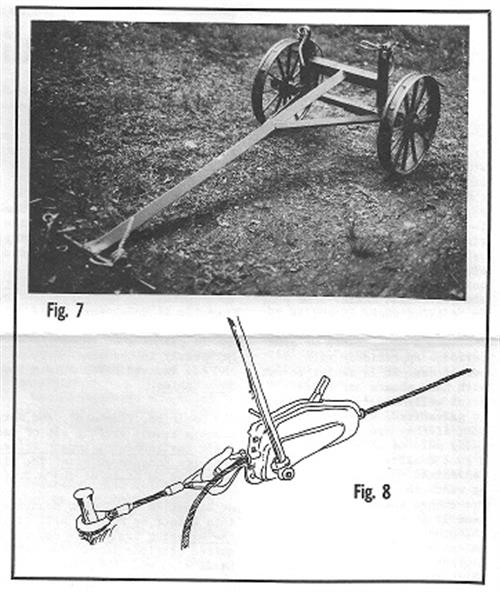

Fig. 7 Cart. The Connecticut Chapter of AMC invented a hand-powered cart for moving logs which were first cut and hauled by tractor to within a half mile of the proposed shelter site.

Club members found metal wheels from an old railroad baggage cart in a junk yard. Then they had a local mechanic cut down the axle to trail width, and build a metal frame. Two people pulled while two pushed on repeated trips until all logs were at the work site.

January 2017 Update: Longtime AMC Connecticut member, Dave Boone, shed some light on the current state of the aforementioned cart. Last used in 2006 to move materials for construction of a new moldering privy at Brassie Brook shelter/camp it has since been retired. While it worked well in the past this cart itself is quite heavy and always proved difficult to maneuver on narrow, rocky trail. Currently, the club has modified a “game cart,” which hunters generally use to haul deer from the woods. Modifications come in the way of placing a flat plywood base where the game would normally go and attaching some tie-down points for attaching webbing, etc. to secure the load. Though not as heavy duty as it’s predecessor the current cart proves much more manageable.

Fig. 8 Clydesdale (Grip) Hoist. “The Clydesdale Hoist has increased our effectiveness on heavy trail construction by 300%” says Lester Kenway, ATC Trail Standards Committee chairman and MATC maintainer. The Model B Clydesdale Hoist, capable of 3,000 lbs. of work force (6,000 lbs. with snatch block pulley), uses a pair of cams in a metal housing to alternately clamp and hold a cable which passes through the housing. Unlike other hoists or come-alongs, the Clydesdale does not require a switch to change from lifting to lowering; the worker simply moves the lever handle to a new position. The Clydesdale will safely hold a heavy load in position. The effective length of the Clydesdale is only limited by the cable length (a 60’ cable is provided by the manufacturer).

The ATC Konnarock Crew found the Clydesdale to be an important tool for their most challenging projects. A second hoist has been purchased by ATC for use in the Mid-Atlantic Region.

Editor’s Note 2017: Hoists are now employed on far more ATC crews and have made their way into use by clubs since this article in 1984. If your club uses one, use the comments section to tell us how or on which of your favorite projects has it been of most use.

Chokers and Dragging. Carl Newhall, an ATC honorary member and the Maine A.T. Club’s shelter chairman, has developed many helpful techniques, of which the simplest and most effective is “Carl’s Choker.” This is a 2-foot loop of spliced ¾-inch hemp rope. The rope is looped over the end of a log and a sapling handle is passed through the rope and twisted to “choke” or hold the log in place. Two to four people can then lift the forward end of the log, and drag it to the work site.

January 2017 Update: “If you’ve got ropes and straps, all you need to do is wrap whatever load you’re trying to move and pull. If traction or grip is required, throwing the strap around the log with a clove hitch works, too. If you’re moving logs, it’s helpful to wait on debarking until the material is near or next to the project area. Leaving the bark on helps with the grip since fresh, green logs can be slick!” -Josh Kloehn, ATC Resource Manager.

Josh goes on to point out that if you’re using webbing straps for dragging and for use with a hoist as an anchor, connection to the winch, or as part of a high-line, be sure to label which straps are used for which purpose since dragging can cause undue wear and strain that may cause potential failure if used under tension with the hoist.

Arm or Shoulder Carry. The most common method for moving small logs is first to cut them to size, then carry them either at one’s side or over one’s shoulder.

Keep the log on the same side of all the workers for safety. The shoulder carry is dangerous and caution should be exercised. Be realistic and think “safety”; e.g., more workers, a lighter log, or abandoning the project. All of these are options are preferable to worker injury.