by Cosmo Catalano, Stewardship Council member

Stream Crossings Task Force Update

Increasingly over the past decade, and more commonly in the past two hiking seasons, hikers have encountered some very challenging stream crossings–particularly in northern New England. In 2023 one hiker fatality occurred crossing a river on the Appalachian Trail in Vermont and several hikers reported “near misses” in similar situations in New Hampshire and Maine. Some clubs are also receiving more frequent communications from Trail visitors describing the difficulty of crossing streams and wondering why a bridge is not provided.

Call it climate change, El Niño, or just another rainy summer, but streams that in previous decades were once fordable most of the hiking season are becoming increasingly challenging, and sometimes have been impossible to ford safely for several weeks at a time. Occasionally, a nearby road bridge may provide an easy alternative; but deep in the backcountry, hikers may be faced with risking a crossing of a turbulent stream with little to no experience, or taking alternative routes that may involve extensive backtracking and long road walks to bypass what were once relatively easy fords.

In the light of these challenges, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) Stewardship Council’s Trail Management Committee (TMC) has assembled a task group to examine A.T. stream crossing policies and provide guidance to clubs and our Trail management partners to assist in evaluating stream crossing options, planning for new or replacement bridges and meeting land-manager requirements. This is a challenging policy area with many critical considerations that range from securing sufficient financial resources to defining and protecting the A.T. hiking experience.

Not all bridges will be automatically replaced. As current bridges age, or become compromised by frequent high water events, clubs are faced with decisions regarding repair, replacement, or removal. The TMC group is working with staff and volunteers to figure out the best options to cross streams–even as environmental conditions and design requirements are rapidly changing. Clubs are also working with the ATC to improve their messaging to hikers and updating educational resources so hikers can learn more about stream crossings before a challenging situation is encountered.

Policy

Current ATC and Agency stream crossing policies are pretty much in harmony: A bridge should be constructed or replaced only if

1. It is essential to hiker safety during the snow-free hiking season, recognizing that a stream may not be fordable when flooding occurs; or,

2. It is absolutely necessary to protect sensitive resources, such as soils, habitat or wildlife along a riverbank or in the stream.

Land Managing Agencies are Responding

The growing increase in high water occurrences is also being noticed by our A.T. agency partners—the U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service Appalachian National Scenic Trail (ANST) Office, and several state agencies. These entities set design standards for major bridges (those over 20 feet long) trailwide. Many are requiring new bridges to be built to exceed the 100 year flood level* by several feet to avoid frequent replacement of these expensive structures.

*The term “100 year flood” does not refer to the water level that might occur once every 100 years, despite the common misconception. The term refers to a flood level that has a 1 percent chance (1 in 100) of happening any year.

Data in the Northeast and in other areas are showing an increasing recurrence interval of “100 year floods,” and agencies are responding accordingly by requiring higher, stronger bridges, often resulting in structures that span the entire drainage from bank to bank.

Are there Downsides to Bigger Bridges (and more of them)?

Bigger bridges are significantly more expensive to build than smaller ones. Larger bridges require heavier structural materials and more substantial foundations. This can result in extremely large bridges, even to span smaller streams. A larger bridge requires more mechanized equipment to construct, which can damage the surrounding natural resources and send costs skyrocketing. Recently, bids for a 55-foot trail bridge in Vermont ran as high as $320,000. With costs this high, agencies are even more motivated to build bridges that will withstand extreme water events (bigger, longer, heavier).

Planning and Design Considerations

Sometimes a bridge is not the best solution for a particular crossing. Here are some key factors that need to be balanced:

- Hiker Safety–Hiking on the A.T. is not without risk. The Comprehensive Plan for the Appalachian Trail states: Hikers must be responsible for their own safety and comfort. Trail design…should reflect a concern for safety without detracting from the opportunity for hikers to experience the wild and scenic lands by their own unaided efforts, and without sacrificing aspects of the Trail which may challenge their skill and stamina. Attempts to provide protection for the unprepared lead to a progressive diminution of the experience available to others.

- Resource protection: The Trail is located for minimum reliance on construction for protecting the resource.

- Desired visitor experience: Different sections of the Trail offer different visitor experiences from wilderness to highly developed front country. Stream crossings should reflect the stated desired experience for that area. Generally there are more unbridged crossings in the more wild areas of the Trail, and particularly in such settings, a large, high bridge may not be in keeping with the desired experience managers are striving to create and maintain.

- Hydrologic Conditions: What factors are at play for a given stream location? Key among them are watershed area, stream channel width, slope (pitch), velocity, bottom and bank conditions and “flashiness”–the tendency for a stream to rise quickly in response to upstream rains.

- Funding: Large bridges can require outside engineering and construction management resources. Even simple bridges can start at $100,000. The A.T. has approximately 414 bridges. 185 of those are over 20 feet long. Funding and construction timelines often run 5 years from conception to completion.

Visitor Communication and Education

Hikers get information about the Trail from literally hundreds of sources and several different kinds of media streams. What is the best way to provide credible and timely information regarding stream conditions to hikers on the Trail? Further, hikers of all kinds may not have previously encountered (as the Maine A.T. Club puts it) “formidable” stream crossings prior to arriving at a swiftly moving watercourse deep in the backcountry. How does a hiker evaluate the conditions of depth, flow and bottom type? What techniques are best for crossing a swiftly flowing stream? What should a hiker do if they choose not to cross?

For long distance hikers, guides like FarOut offer the opportunity for near real time information on stream conditions (if there is sufficient cell reception) and hiker-to-hiker communication can be very effective. However, most visitors to the A.T. are not long distance hikers, and different communication tools are needed to reach all visitors. Signage at trailheads and at “bail out” opportunities can alert hikers to the possibility of a difficult crossing, but do not provide real time information on current conditions. All hikers should check out weather forecasts in advance, become familiar with stream crossing techniques, and make plans for addressing what may lie ahead.

Visit ATC’s Plan and Prepare pages for helpful information about stream crossings and other safety tips.

For more information about planning a project and the facilities on the Appalachian Trail, visit the Trail Management pages.

Discover More

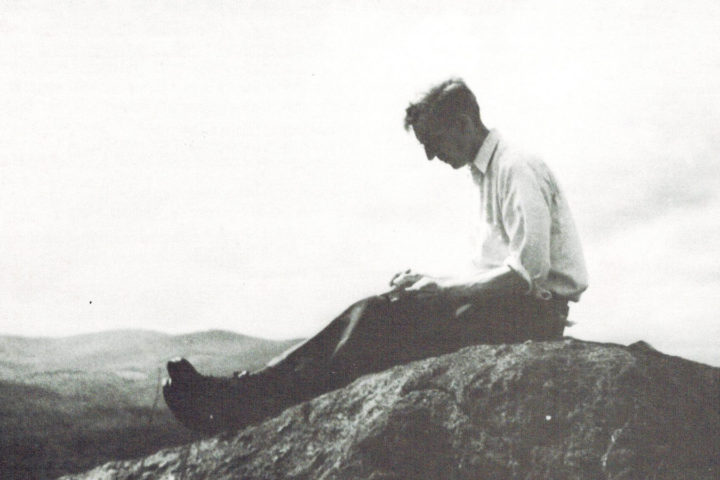

By Benton MacKaye

“An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning”

Originally published in October 1921, Benton MacKaye's article establishing the idea for the A.T. still inspires and guides the ATC's efforts today.

Policies Guiding a Cohesive A.T. Experience

Policies

A unified approach to the care of the A.T. takes coordination and cooperation among a number of partners. Learn how the ATC works with Cooperative Management Partners to define policies that bring consistent management to 8 national forests, 6 national park units, 14 states, and numerous state and local jurisdictions.

Learn More

Volunteer Orientation

An orientation for A.T. volunteers, as well as for those interested in volunteering along the Appalachian Trail!