By Kim O’Connell

Warriors in the Woods

November 11, 2022

When Sean Gobin embarked on a thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail (A.T.) in March 2012, he tackled it as if he were back in the military doing a grueling training hike. His gear was heavy, his pace was relentless, and his mindset was all about gritting his teeth and getting it done. That lasted all of three days. Blistered and exhausted, Gobin realized that he needed to focus on the long game and approach the Trail in a way that was healthier for both his mind and body.

“I switched out my gear, started taking my time, and learned to eat and drink properly,” Gobin says. “I was a mess until about Virginia, but by then I had my routine down. It was springtime — the flowers were blooming, the trees all had leaves on them. I started to enjoy the experience and could focus externally versus internally. I started to decompress.”

Decompression time had been in short supply for Gobin over the previous 12 years. As a U.S. Marine, Gobin was an infantry rifleman and armor officer with three combat deployments, two to Iraq — including the brutal battleground in Fallujah — and one to Afghanistan. After his last deployment, Gobin processed out of the military and had about six months before he was to start graduate school to earn an MBA. He knew that there would be no better time to thru-hike the Trail, a dream of his since before he joined the Marines.

Setting a New Goal

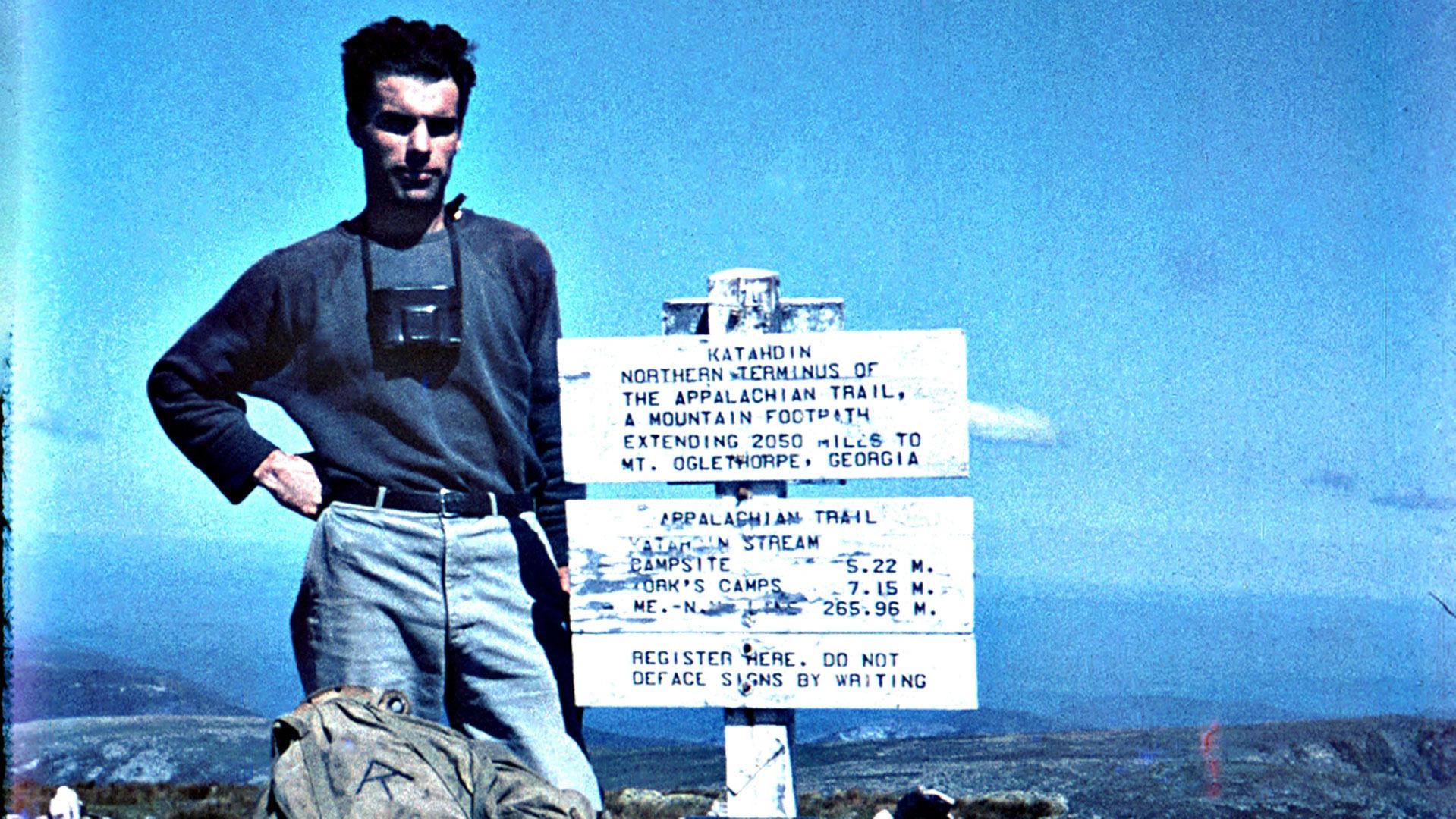

Gobin is far from the first veteran to find a source of rejuvenation and decompression on the Trail, especially in springtime. It’s something Earl Shaffer experienced nearly 75 years ago and wrote about in his memoir, Walking with Spring. In 1948, Shaffer, a World War II veteran, set out on the A.T. “to walk the Army out of [his] system, mentally and physically.” In doing so, Shaffer became the first person to hike its entire length in one push, averaging over 16 miles a day (he would complete thru-hikes again in 1965 and 1998, the last time accomplishing the feat when he was 80 years old).

World War II veteran Earl Shaffer stands on the summit of Katahdin at the end of his 1948 thru-hike, becoming the first known A.T. thru-hiker.

Before the war, Shaffer had hiked sections of the Trail with a childhood friend named Walt Winemiller. When Winemiller was killed in action at Iwo Jima, Shaffer decided to complete the trek himself, taking careful notes of his experience, both as proof of his continuous push and to work through what he was feeling and seeing. “Wrote poem,” his diary reads, written when he was somewhere near the Tennessee-North Carolina border. “Went on over good terrain rest of morn. Passing down long grassy inclined ridge, came to lonely grave of soldier.”

With his groundbreaking thru-hike, Shaffer set a new goal for thousands of other hikers and opened a door to healing for fellow veterans like Gobin. “When you’re in the military, you’re in what’s called the deployment assembly line,” Gobin says. “When you process out, that’s a 100-mile-per-hour process and then, boom, you’re out. But you’re still in fight-or-flight mode. Often you deployed, you came home, and you just pack everything away. Being on the trail 12 hours a day, your brain finally has the opportunity to go back and process all of it.”

Stronger in Body and Spirit

Inspired by his own therapeutic experience on a long-distance hike, Gobin in 2013 founded Warrior Expeditions, a nonprofit outdoor therapy program that helps veterans transition from wartime service through long-distance outdoor expeditions. The Department of Veterans Affairs reports that about one in five post-9/11 veterans suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety and depression are rampant. To help other veterans, Warrior Expeditions began with exclusively A.T. thru-hike experiences but has now expanded to include other long-distance hiking opportunities such as the Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide Trail, bike treks on the 3,700-mile Great America Rail-Trail, and a paddle adventure down the Mississippi River.

U.S. Veteran William D. “Saber” Sam celebrates the completion of his 2013 A.T. thru-hike by displaying an American Flag from his tour in Iraq. According to military guidelines, the union field (the blue square containing 50 stars representing all U.S. states) will often be positioned on the right to give “the effect of the flag flying in the breeze as the wearer moves forward.”

The emotional and physical benefits of being in nature are well-known, but what a long-distance trip provides, Gobin says, is the time and space to process the trauma that often comes with a military career, particularly one with combat experience, while re-socializing veterans who might feel uncomfortable back in a civilian world.

To date, Warrior Expeditions has helped about 300 veterans via expeditions, and veterans usually come out of it stronger in body and more settled in spirit. “You get out of the service and maybe you’re taking medications, so a lot of veterans end up gaining weight, their sleep schedule is messed up, they’re out of shape,” Gobin says. “After over 2,000 miles, you’re in better shape than when you were in the military, so you regain your sense of physical fitness. You’re exhausted at the end of every day so you’re going to sleep with the sunset and waking up with the sunrise. There’s a lot of improvements that form the baseline for getting healthy.”

Beyond the veterans participating in Warrior Expeditions, the A.T. draws dozens of veterans to the Appalachian Mountains each year, with many seeking their own solace with nature. In 2022 alone, 98 veterans have reported their completion of the entire A.T.

“We know that the reasons why veterans seek out the Appalachian Trail each year are as diverse as veterans themselves,” said Dakota Jackson, director of visitor services for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. “Many hike in remembrance of lost companions, for their own self-healing, or to find community again. We’re constantly moved by all of these stories and are humbled to know that the work of the ATC, our volunteers, and all of our partners in maintaining the Trail helps give something back to those who have already given so much for our country.”

Boot Camp, in Reverse

Social engagement on the Trail is essential to healing, too. “A lot of veterans come out cynical about people because they have seen people at their worst,” Gobin says. “So a lot of veterans isolate. But to get on the Trail and meet people from all walks of life, learning about new things, to see all the community supporters, it re-establishes a basic faith in humanity that you might have lost along the way.”

For Army veteran Mike Adams, planning his thru-hike in 1995 gave him something to look forward to and focus on as his military career was coming to an end. He’d pinned a map of the entire A.T. on the wall of his office, and beginning at Springer Mountain, each day he’d move a pushpin to a location farther down the Trail, as he imagined himself completing the hike. “When I took the map off, there were pin marks up and down the wall,” Adams recalls with a laugh.

A U.S. military veteran takes a break to absorb the views in Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Photo courtesy of Warrior Expeditions

The Trail helped Adams learn to relax, giving him some recovery time before he launched into a civilian career. “I spent half my career with soldiers, troop units, and you go out into the field a lot,” he says. “You put all your battle gear on, you’re up 30 minutes before dawn, being alert. I found I would wake up early in the morning and feel like I had to go put my gear on and check the perimeter. Camping on the Trail, there’s a certain smile that comes when you can go back to sleep and say to yourself, ‘I don’t have to do that.’ The only thing you need is on your back. All you need at night is a flat spot. There’s a shelter, there’s a picnic table, there’s a spring. It was the ecstasy of small pleasures.”

Think of it as boot camp, but in reverse, Gobin says: “In the military, you’re going from the line of departure to the objective as quickly as possible. Thru-hiking offers something different. It’s adventurous, it’s challenging, it’s community and camaraderie. Boot camp trains you for war; thru-hiking trains you to go back into society.”

From all of us at the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, thank you to the military veterans who have given so much for our country.

Kim O’Connell writes about science, history, conservation and sustainability for a range of national publications. She has served as a writer-in-residence at Acadia and Shenandoah National Parks and teaches in the Johns Hopkins University Master’s in Science Writing program. Learn more: kimaoconnell.com.

Kim O’Connell writes about science, history, conservation and sustainability for a range of national publications. She has served as a writer-in-residence at Acadia and Shenandoah National Parks and teaches in the Johns Hopkins University Master’s in Science Writing program. Learn more: kimaoconnell.com.

Discover More

Learn More

About the ATC

We are the stewards of the world’s longest hiking-only footpath, the Appalachian Trail.

ATC's Official Blog

A.T. Footpath

Learn more about ATC's work and the community of dreamers and doers protecting and celebrating the Appalachian Trail.

Stay Informed

Latest News

Read the latest news and updates about the Appalachian Trail and our work to protect it.