By Roland “Tony” Richardson

A Hike Through History

February 13, 2017

Following the Path of the Underground Railroad

In October 2016, a group of seven African-American outdoor enthusiasts embarked on a four-day backpacking trip on the Appalachian Trail (A.T.). The group was organized by Brittany Leavitt, a leader with Outdoor Afro — one of the nation’s first black-led conservation organizations. Joining Brittany were six other Outdoor Afro Leaders from across the country, some traveling from as far as California. The group traversed over 40 miles along the Blue Ridge Mountains in an attempt to retrace the historical route of the Underground Railroad, following the path Harriet Tubman may have taken. No one on the trip had ever been hiking on the A.T. before.

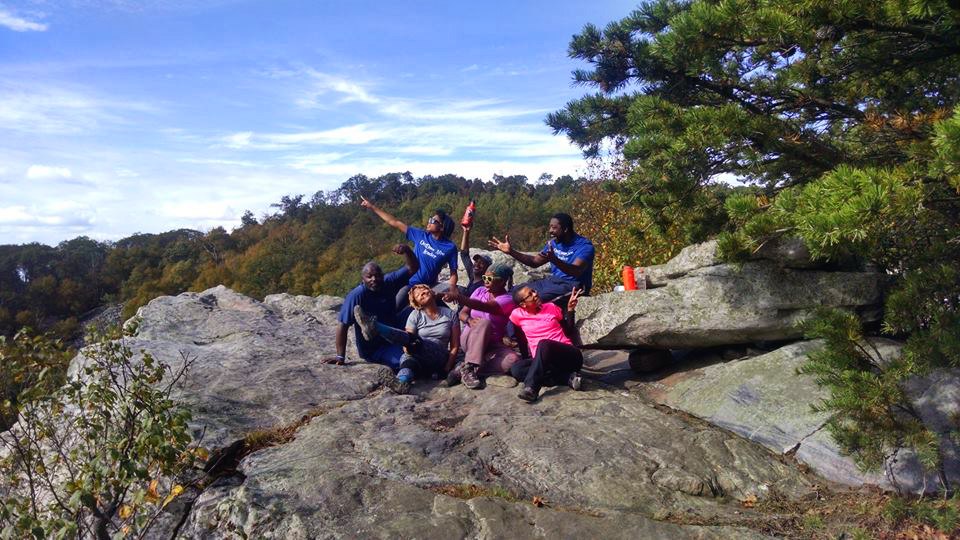

Front row, from left: Beky Branagan. Kelly Thomas, Melody Graves, Brittany Leavitt. Back row: Valarie Morrow, Cliff Sorell, Christopher Robinson.

Front row, from left: Beky Branagan. Kelly Thomas, Melody Graves, Brittany Leavitt. Back row: Valarie Morrow, Cliff Sorell, Christopher Robinson.

The group set out on October 6 from the Mason-Dixon Line, which separates Maryland and Pennsylvania and serves as the most traditional border between northern and southern United States. They hiked for four days at an average of 10 miles per day until reaching their final destination of Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Brittany described the hike as “amazing, very peaceful and calming,” and that “everyone displayed great teamwork and high spirits in spite of a torrential downpour.”

During the hike, the group imagined what it must have been like for freedom seekers to navigate the difficult terrain with no gear. Some members of the group had never been on an overnight backpacking trip and were hesitant to spend four-to-five nights on the Trail. The group addressed these concerns through diligent preparation.

In order to ensure participants were adequately prepared for the physical toll of 40 miles over four days, Brittany encouraged the group to train. Starting in April — a full six months out from the planned departure date — the group had weekly check-ins to monitor progress, trade training tips and keep each other motivated. The group also coupled less-experienced hikers with more experienced members. This helped cut down on the amount of gear the rookie hikers needed to purchase for the trip and ensured each would have a knowledgeable hiking buddy to help build confidence. This careful preparation and attention to detail was critical to the success of the hike.

On top of this preparation, the history behind the hike was a continual source of inspiration for the group.

The Underground Railroad, formed in the early 19th century, was a network of secret routes and safe houses used by enslaved people of African descent in the southeastern United States to escape to the “free states” in the North. There were many different routes that slaves took as they traveled north to freedom. One route through Maryland was frequented by the most famous “conductor” for the Railroad, Harriet Tubman. Due to its geographic location, tough terrain and an abundance of hiding spots, the forested corridor along the mountains was an ideal route for freedom seekers escaping to the North. In a historical deposition, John Rodes wrote about the Underground Railroad and his brother in-law Abraham Heatwole, another conductor who was a landowner and farmer in Virginia: “His house was a kind of depot for refugees and deserters. He had a very good place for concealing them where they could not be found.” Undoubtedly, the success of this “depot” can be owed partly to the ruggedness of the surrounding Appalachian landscape.

The Underground Railroad, formed in the early 19th century, was a network of secret routes and safe houses used by enslaved people of African descent in the southeastern United States to escape to the “free states” in the North. There were many different routes that slaves took as they traveled north to freedom. One route through Maryland was frequented by the most famous “conductor” for the Railroad, Harriet Tubman. Due to its geographic location, tough terrain and an abundance of hiding spots, the forested corridor along the mountains was an ideal route for freedom seekers escaping to the North. In a historical deposition, John Rodes wrote about the Underground Railroad and his brother in-law Abraham Heatwole, another conductor who was a landowner and farmer in Virginia: “His house was a kind of depot for refugees and deserters. He had a very good place for concealing them where they could not be found.” Undoubtedly, the success of this “depot” can be owed partly to the ruggedness of the surrounding Appalachian landscape.

While many have tried to find a direct link between the current course of the A.T. and the historical route of the Underground Railroad, we may never find definitive evidence due to the necessity of secrecy surrounding the routes. Yet despite the lack of a concrete connection linking the Trail and the Underground Railroad route, Tubman’s legacy was constantly on the minds of the Outdoor Afro crew as these seven hikers traced what could have been Tubman’s path to freedom. The Railroad’s route may have been different than that of the A.T., but the connection with the area’s past can still be felt with every footstep.

While most Americans know that Harriet Tubman was an Underground Railroad conductor, far fewer know that she was also considered an expert naturalist. According to Dr. Dann J. Broyld, a Professor of History at the Central Connecticut State University, “Tubman worked closely with the earth’s riches whether as a muskrat trapper, lumberjack, or conductor of freedom seekers. … Tubman’s love of the natural world included: flowers, trees, animals, and the stars. This naturalist disposition served Tubman well while she navigated Blacks from Maryland to the American North and British Canada. This enterprise took knowledge of the waterways, wind patterns, geography, forestry, interpretation of astronomy, even the understanding of herbal medicine and healing.”

By the mid-to-late 20th century, the deep ecological understanding of the Shenandoah Valley was largely forgotten. Furthermore, barriers were being put in place which would systematically reduce the ability of African-Americans to connect with nature. In the early 1930s, the National Park Service began planning segregated park facilities and some states, including Virginia, tried to ban black people from their parks entirely.

The underrepresentation of communities of color in the outdoor recreation space has been well documented. A 2013 study by the Outdoor Foundation noted that, in the previous year, 70% of Americans who participated in some form of outdoor recreation — hiking, camping, rock climbing, canoeing, etc. — were white.

Addressing this inequity is the central mission of Outdoor Afro. The organization has emerged as the nation’s leading, cutting-edge network that celebrates and inspires African-Americans to connect with nature and take positions of leadership. Today, with over 60 leaders in 28 states from around the country, the organization is successfully connecting thousands of people to outdoor experiences and helping to change the face of conservation.

By exploring the historical relationship of communities of color and the outdoors, these hikers have helped to unearth the history that shows there always has been a place for people of color in the environmental movement. This hike has shown that regardless of age, skin color, or experience, it is never too late for anyone to forge a deeper connection to the A.T.

Special thanks to Brittany Leavitt and Outdoor Afro for sharing their story. The author would also like to thank his friend Harriet Rowan for her help editing this article.

Additional Sources:

- Dianne D. Glave, Rooted in the Earth: Reclaiming the African American Environmental Heritage. (Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press, 2010).

- Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2005), 353.

For more information about Outdoor Afro, visit OutdoorAfro.com.

Discover More

Official Blog

A Commitment to Justice

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy has taken inventory of the social landscape within the Appalachian Trail community and across the United States, and we believe that by making meaningful changes, the A.T. can be a space that is inclusive, open and safe for all.

ATC's Official Blog

A.T. Footpath

Learn more about ATC's work and the community of dreamers and doers protecting and celebrating the Appalachian Trail.

Stay Informed

Latest News

Read the latest news and updates about the Appalachian Trail and our work to protect it.