The Sky Begins at Your Feet

Nov 15, 2019

Tyler Nordgren

Nov 15, 2019

Top photo by Tom McMahon / photo courtesy of the Rangeley Chamber of Commerce. Originally featured in the Fall 2019 issue of A.T. Journeys Magazine.

I don’t know why you get out on the Appalachian Trail, but for me it’s always been an escape. Going for a hike powered by my own two feet and sleeping under the stars, I can escape the modern world. For huge stretches of Trail, I lose sight of the 21st Century and walk through a world of trees, streams, waterfalls, and mountains. As light pollution increases though, that sense of escape becomes more difficult at night.Just the phrase, “sleeping under the stars” evokes an image of childhood for me. I was a Boy Scout in Oregon and then Alaska as my father moved from one job to another. As a kid, I first saw the Milky Way from the Pacific Crest Trail near Mount Hood in Oregon and still remember what it was like seeing a sky splashed full of stars reflected in the lake beside which we camped. It was our universe: an infinite expanse even greater than the distant ridgeline of trees or the more distant mountains of the Cascades to north and south. I felt I could get lost in that starry sky and who knows what wonders there might be out there among those stars? In Alaska, I fell in love with the aurora borealis during the long dark winter months and still remember what it was like to have them light up the snow around me on the frozen lake where our troop had set up our tents. No wonder I eventually became an astronomer.

But even as I gained access to some of the world’s largest telescopes and wrote papers on dark matter and pulsating stars, I never forgot where my love of the sky started. I once spent a year traveling the country working with National Park Service rangers and writing a book on all the ways visitors could experience astronomy in the parks. I led tours to see the aurora in Alaska and have trained river rafting guides in the Grand Canyon how to answer the question, “what star is that?” and “why are there so many more stars here than at home?” Because those visions of stars, the Milky Way, and even the northern lights, are becoming harder to see every year.

Eighty percent of Americans and Europeans can no longer see the Milky Way from their homes. When I first started paying attention to this issue back in 2005, that number was 66 percent, so getting to experience a dark sky is becoming more elusive and requires greater travel every year. Yet, even when I am able to finally reach a place where I can see the Milky Way overhead, often it is just a pale imitation of what it could be. Artificial light knows no regional boundary and distant cities and towns (or coal mines and oil wells) create “light domes” that illuminate the clouds, cast shadows on the ground, and reduce the light of our galaxy — the light of over 400 billion stars — into a faint smear across the sky. The world around me that I have come to see in all of its beauty is being rendered pale and muted at night. We have allowed a fog of light to blow in on our natural landscape and render the universe beyond our own atmosphere a little more invisible every year, and it has happened so slowly that few have even noticed.

I’m an astronomer, but I’ve also traveled all over the world to observe the sky both professionally and as a tourist (and now tour leader). I’ve seen the heart of our galaxy from the Outback in Australia and high in the Chilean Andes after a solar eclipse. I once stargazed my way across the Atlantic on a four-masted sailing ship and I’ve seen a star-filled sky while hiking the Continental Divide. I care about the darkness because I know what I am missing due to light pollution. But why should anyone else?

The A.T. hikers guide to the galaxy

The A.T. hikers guide to the galaxyDark Night Skies vary along the Trail and are often dependent on the amount of protected lands that surround the footpath and its proximity to urban areas. Just as the landscapes surrounding states the Trail runs through can be fragmented, some areas along the Trail are more prone to light pollution. These two issues go hand in hand. In general, as the corridor of protected land around the Trail decreases, the light pollution increases.In general, Maine and the northern New England states are the best places along the Trail to enjoy dark night skies. In Maine, the area surrounding Rangeley — a community that is the gateway to the Bigelow Mountain Range — is a great spot to view night skies as well as along the A.T. in the Green Mountain National Forest in New Hampshire. Areas in the south around Mount Rogers in Virginia and Clingmans Dome in the Smokies in North Carolina and Tennessee are also some of the better places for experiencing dark night skies. These areas are farthest from high density populations and have the added benefit of elevation. Some states have “dark sky” designated parks, communities, or areas. The International Dark Sky Places conservation program recognizes excellent stewardship of the night sky. Designations are based on stringent outdoor lighting standards and innovative community outreach.

Other Notable Dark night sky viewing along the A.T.

/ Chestnut Ridge looking down onto Burkes Garden near Bland and Burkes Garden, Virginia

/ Nantahala National Forest near Franklin, North Carolina (e.g. Wesser Bald)

/ Little Hump Mountain and Big Hump Mountain in North Carolina

/ Doll Flats in Tennessee

/ Chattahoochee National Forest — Gooch Gap and Hickory Flats in Georgia

The Wild East initiative acknowledges that what makes the Trail special is more than just the dirt of the path. It’s the landscape around it, an interconnected tapestry of plants, animals, waterways, geography, and sky. Sacrifice any one of these threads and the cloth unravels. The sky is an integral part of that whole. Think about the nocturnal animals that hunt, feed, mate, and survive under the darkness of night. Under most skies in the eastern United States, true darkness no longer falls. In more urban areas along the Trail, the sky can be almost as bright as moonlight, every night, especially on nights where clouds reflect our urban lighting back down to us. Yet hikers can still find pockets of darkness in some of those areas, shielded by the mountains in the Wild East landscape (near Pawling New York for instance).

Astronomers are not the only species that depend on darkness to thrive. Take fireflies for instance. I’d never seen a firefly before moving to the East Coast. Even today after 25 years I think they are still an utterly magical sight blinking and flashing in a wooded darkness. Recent research shows female fireflies exposed to increasing ambient light do not flash back to males as much as those under natural darkness and thus decrease their chances of finding a mate. How much would we lose to live in a world without fireflies?

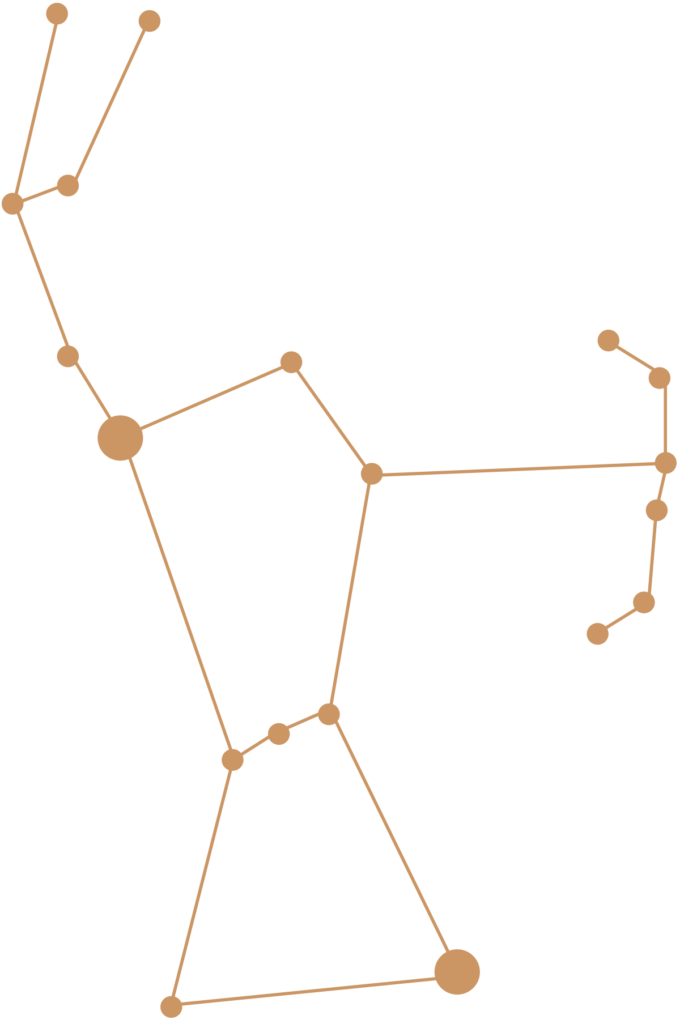

Birds navigate by the stars. Their seasonal migrations spanning multiple continents put even the most avid A.T. thru-hiker to shame. Yet the constellation of city lights that grows ever brighter — and increasingly blue-white like the stars overhead thanks to the advent of LED streetlights — appears to throw that navigation into disarray. Who among us could imagine any place claiming to be “wild” that didn’t have birds? Orion is a prominent constellation located on the celestial equator and visible throughout the world. It is one of the most conspicuous and recognizable constellations in the night sky. It was named after Orion, a hunter in Greek mythology. Its brightest stars are the supergiants: blue-white Rigel and red Betelgeuse

Artificial light knows no regional boundary and distant cities and towns create “light domes” that illuminate the clouds, cast shadows on the ground, and reduce the light of our galaxy — the light of over 400 billion stars — into a faint smear across the sky.

This change to our nocturnal landscape has been slow, but is picking up speed, especially as communities all across the country change their street lighting to the less yellow and more white LED lighting. Unless you have actively looked for it at night, you probably haven’t noticed the change. But the number of people who tell me they remember there being so many more stars when they were kids grows every year.

One way to gauge how much light has affected your view of the sky and how non-pristine your sky may be, is by consulting the Bortle Scale. A Bortle class of 9 is an inner-city sky so bright that only a handful of the brightest stars are visible, none making up even a full constellation beyond maybe the Big Dipper. Under a Bortle class 9 night, the Milky Way is completely invisible and city lights illuminate the clouds overhead and your eyes never fully adapt to the darkness. At the other end is a Bortle class 1 sky that is utterly pristine, with no light domes even faintly visible on the horizon and a sky so dark that clouds (and even your hand in front of your face) are just a dark hole on the sky. The Milky Way from these locations is visible all the way to the horizon and looks so bright that the dark clouds of interstellar gas and dust that span the light years throughout our galaxy, render the Milky Way overhead richly veined as if it was carved from celestial marble.

Believe it or not, while the sky above nearly every major population center is classified on a Bortle Class 8 or 9, there are literally fewer than a dozen regions in the continental U.S. that are still Bortle class 1. While most of these pristine skies are in the Western U.S. along the Continental Divide and Pacific Crest Trails, one is in the East and it is in the area around Katahdin at the northern end of the Appalachian Trail in Maine. There are many maps you can find online that will show you light pollution and Bortle scale maps for the country, and I’ve even published a small field guide that shows you the Milky Way at different times of year and how to estimate the Bortle brightness for wherever you happen to be. Think about that the next time you go out for a hike or just outside your front door at night. Think how much the lights of our civilization have already altered our wild places, even areas hundreds of miles away from major cities.The Big Dipper is an asterism in the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. It’s seven stars are one of the most familiar shapes in the northern sky. It is a useful navigation tool. The Big Dipper’s outer edge of its “bowl” will always lead you to the North Star.

The nice thing about light pollution is that, unlike nearly all other forms of pollution, the minute you stop producing it, you’ve restored the darkness of the sky at the speed of light.

The nice thing about light pollution is that, unlike nearly all other forms of pollution, the minute you stop producing it, you’ve restored the darkness of the sky at the speed of light. The way to be more night-sky friendly at home and in your community is to behave like you would on the Trail. A hiker whose headlamp shines right in my eyes produces glare that ruins my night vision and makes it harder to see what’s around me. Same thing at home: street lights and house lights that shine directly in your eyes don’t make you safer at night, in fact, they make it harder to see what’s around. Similarly, don’t put a flood light in your camp that shines on all your neighbors; this is called light trespass. If you have to have a light outside at night, put a shade on top that restricts light to only shining downward. In camp, use only as much light as is needed and don’t leave it on all night, same thing at home. Red head lamps on the Trail don’t ruin your night vision, and yellowish lamps (not the blue-white ones that seem to be everywhere now) don’t attract as many insects. Now, if only communities would do the same and swap out those new blue-white street lights or at least cover them with yellower filters, we’d all be a lot more night sky friendly and see more stars without sacrificing safety.

The International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) provides some informative apps that can be used to measure light pollution including:

Find out more at: darksky.org

When using any apps, the IDA advises to: “respect other people and surrounding natural areas in dark sky destinations by dimming the glow of smart devices while in the company of others.”

This zoomed-in shot of the NASA Blue Marble Navigator map shows the light pollution over the eastern United States.

Dr. Tyler Nordgren is an unusually gifted artist, astronomer, and author. Tyler is well-known for his contemporary series of “Milky Way” posters for dozens of national parks and his series on the 2017 eclipse, which are now part of the Smithsonian collection. His commissioned artwork of the Appalachian Trail presents some of the Trail’s attributes in a fresh new way, reminiscent of vintage “See America” posters.

Dr. Tyler Nordgren is an unusually gifted artist, astronomer, and author. Tyler is well-known for his contemporary series of “Milky Way” posters for dozens of national parks and his series on the 2017 eclipse, which are now part of the Smithsonian collection. His commissioned artwork of the Appalachian Trail presents some of the Trail’s attributes in a fresh new way, reminiscent of vintage “See America” posters.

“We are driven to conserve what we value, and we value what we know,” says Tyler. “For me, this project helps share the wild beauty of the eastern U.S. and the need to protect and conserve it just as we would the canyons, arches, and mountains out west.”

Get the latest A.T. news, events, merchandise, and sneak peeks delivered directly to your inbox.