By Mills Kelly

How the A.T. Almost Lost Its Shelters

August 21, 2025

Every few years, it seems that someone proposes scraping off all 250-plus shelters on the Appalachian Trail. Sometimes a proposal is offered as a solution to overcrowding on specific sections. Sometimes removing the shelters is seen as a way to make the Trail “more difficult,” thereby scaring away those who don’t have the gumption to do the hard work of a long-distance hike.

Of course, those proposals haven’t gone anywhere, because the Trail shelters are an intrinsic feature of America’s most iconic long-distance hiking trail. And they have been since 1937, when the ATC initiated a program in cooperation with federal and state land managers for the completion of a chain of lean-tos along the entire route of the Trail.

But there was a moment in the early 1970s when the ATC and the Trail Clubs seriously debated removing all the shelters. In fact, the ATC went so far as to survey its members and the leaders of all the Clubs to ask whether the shelters should be replaced with designated campsites.

I spent a few days in the ATC archives reading the responses to that survey, and I think it’s fair to say that a large segment of the Trail community was fed up with the increasing frequency of vandalism and huge piles of trash accumulating at many of the shelters.

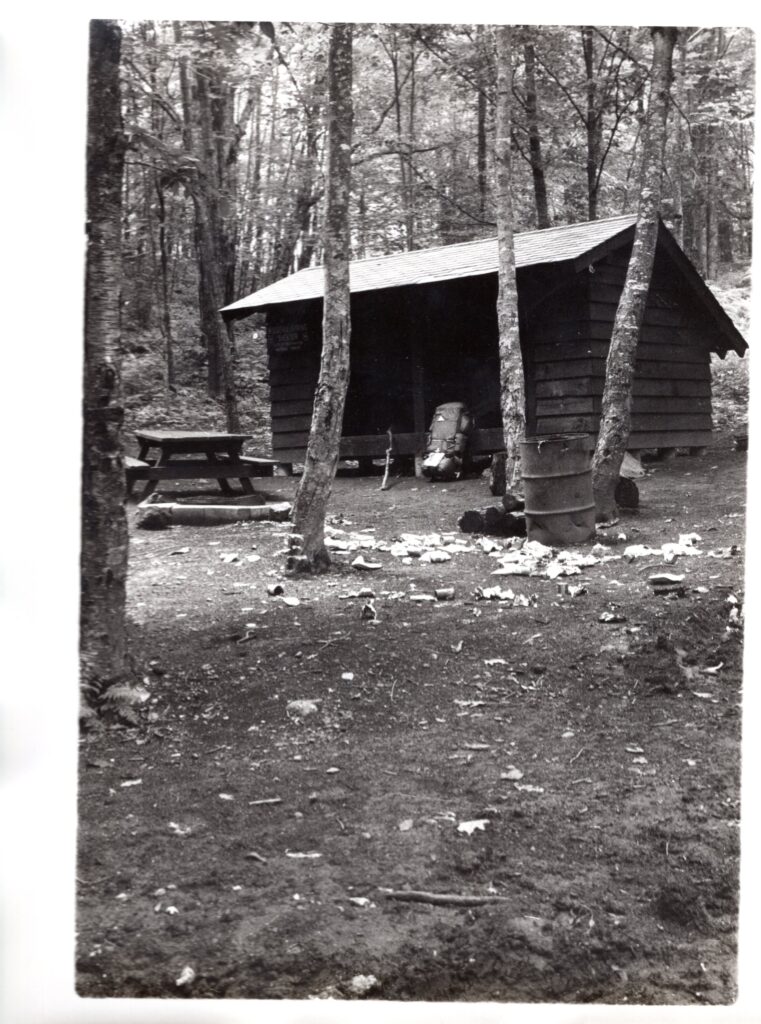

Moreland Gap Shelter

Here are a couple of comments I found that indicate just how unhappy hikers and maintainers were with the current state of affairs.

Vandalism is a growing, unchecked problem and one of the main reasons why our shelters have a dubious future. I have seen many shelters that have more bullet holes in them than the Alamo.

The shelter system on the A.T. (except in national forests) is obsolete. The shelters I am acquainted with in Pennsylvania are in such sad shape that most of them should have been removed long ago.

It angers me to realize that people have invested their own time, money, and talents into building shelters only to have them destroyed by callously indifferent vandals.

Fortunately, as I detail in my forthcoming book, A Hiker’s History of the Appalachian Trail, cooler heads prevailed. Still, the ATC and the maintaining Clubs agreed that something had to change. Their solution was a three-part strategy.

Wiggins Spring Shelter

Shelter Relocation

Most of the real problem shelters, like Wiggins Spring in Virginia (pictured right), were close to roads. Over the next few years, most of those shelters were removed or relocated to less accessible locations farther from roads. Some of the Clubs posted volunteers at their most abused shelters during peak hiking season.

Visitor Education

The ATC also began to invest in what they called the “On the Trail Education System,” one of the several precursors to the national Leave No Trace campaign. The new effort sent volunteers and paid staff to meet with hikers on the Trail and educate them about wilderness ethics (and at the same time keep an eye out for problems at certain shelters). Today’s Ridgerunner program derives in part from this earlier approach to meeting hikers on the Trail, helping them be better hikers and better stewards of the landscape.

Shelter Closures

In Shenandoah National Park, things got really out of hand. In 1974 the park’s superintendent closed the shelters completely (except in the case of a weather emergency) and the park began leveling fines on hikers who ignored the closure. As I detail in the book, it took almost a decade for the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club and ATC leaders to convince the park to reopen the shelters there.

Speaking as one of those hikers who thought they could sneak into a park shelter after dark and no one would be the wiser, I can say with certainty that rangers definitely stopped by well after hiker midnight. And they weren’t very polite when they found a couple of college-aged hikers snoozing comfortably inside.

A.T. Shelters Today

Today, the Trail’s shelter system remains a vital part of the A.T. experience, offering hikers a place to rest, connect, and share stories while reducing the impacts of dispersed camping. Thanks to decades of stewardship by volunteers, the ATC, and our partners, shelters are well-maintained, thoughtfully located, and supported by on-the-Trail education efforts like the Ridgerunner program.

“Legolas” and “Rockman” relax at the Fontana Dam Shelter. Photo by Michael “Ishkabibbel” Nieves (@kryptic_blue)

A.T. visitors can help protect shelters by practicing Leave No Trace, packing out trash, treating shelters with respect, and volunteering to help care for them. Learn more about the ATC’s work to make the A.T.’s overnight sites more sustainable.

Discover More

BACK TO THE BASICS

Leave No Trace

Wondering how you can take care of outdoor places like the Appalachian Trail (A.T.)?

Plan and Prepare

Register Your Hike on ATCamp

In addition to reserving your A.T. Hangtag, registering your hike on ATCamp can help prevent crowding and preserve the Appalachian Trail hiking experience.

Plan and Prepare

Hiker Resource Library

A collection of resources for hikers to stay safe, healthy, and responsible on the Appalachian Trail.