By Trey Adcock

Native Lands

February 23, 2021

It is late September, and we are on a 5.5-mile section of the Appalachian Trail in present day southwest North Carolina looking for wisi, a mushroom more popularly known as Hen of the Woods, Grifola frondosa. There are three of us, myself an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation (CN), an Elder, Gilliam Jackson, from the Tutiyi “Snowbird” community of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) and Devyn Smith, a twenty-something year old, fresh out of college who grew up in the Yellowhill community on the Qualla Boundary. To us, this land is Tsalagi Ayehli, Cherokee Nation territory. To most, however, this is known as Nantahala National Forest.

The morning is crisp and the clouds are thick but breaking as we traverse this section of the Trail. We make good pace as this portion is mostly level with only a couple of moderately steep climbs. As we walk, we spend time making fun of each other, catching up on community news and tribal politics while patiently looking for any signs of wisi. This delicacy continues to be one of the most coveted foods of Cherokee people and we are in an intense search for our first harvest of the year. As we log a couple of miles, Devyn and I are struggling to keep up. Gill is a prolific hiker, having completed the A.T. in 2016, and he seems to glide atop the Trail while using Cherokee words to name plants, trees, colors, and an animal or two. With only 200 or so fluent EBCI Cherokee speakers remaining, words are precious. Gill graciously teaches us names in the language and we recite, desperately trying to remember.

Like the language, the harvesting of plants and wild foods is a knowledge bounded to the land. One of the many results of the forced removal and genocide of thousands of Native Americans from the southeast U.S. was that of rupturing Indigenous peoples from their food systems. While many families have held onto that knowledge, others still are looking for a way to reclaim those cultural practices that center us in who we are. Thus, this search is not simply about looking for wisi but is also an act of resistance, resilience, and reclaiming. Finally, three miles into our journey, we catch a glimpse of the most beautiful wisi we have ever seen, right off the Trail at the base of a dead oak tree. We are exuberant as we all claim to have been the first to see it. We laugh, we give thanks, and we acknowledge the special relationship and responsibility we all have to the land that provides so much.

Land acknowledgement at a base level is a recognition that you are on the lands, for various purposes, of an Indigenous people.

The A.T. in the North Carolina portion of the Nantahala National Forest runs along Cherokee Nation territory.

– By Jerry Greer

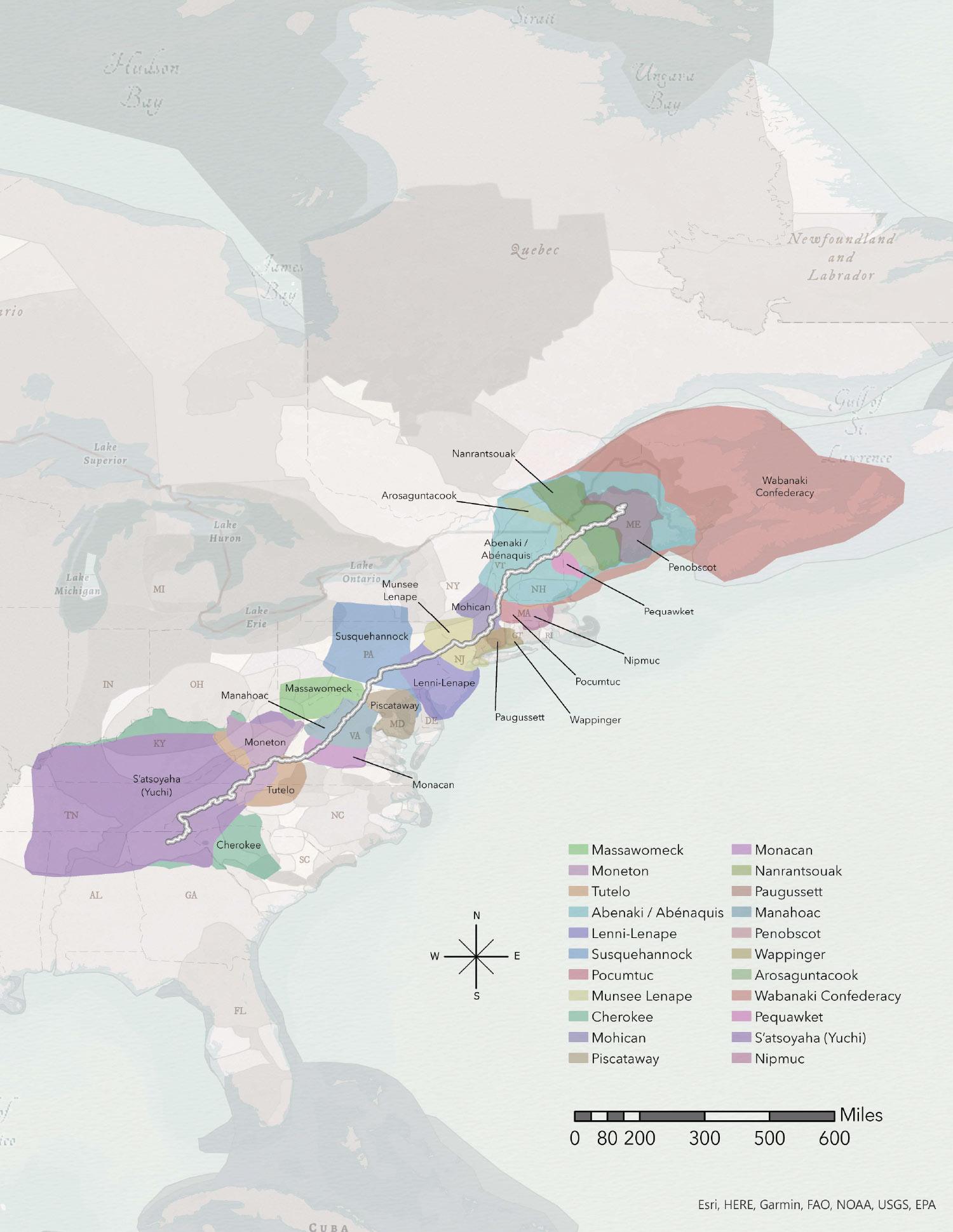

The Appalachian Trail runs through 22 Native Nations’ traditional territories and holds an abundant amount of Indigenous American history. The A.T. Native Lands Territory map was created to provide A.T. hikers with a better understanding of the territories they are traversing through. These lands are also referred to as “territories of influence,” meaning this is land that Indigenous American nations and tribes hunted, traded, foraged, and defended. Beyond educating hikers, we must pay respect to our nation’s ancestors.

Our primary source of spatial data in creating the A.T. Native Lands Territory map originated from Native Land Digital (native-lands.ca), whose friendly and accommodating team pointed us in the direction of their publicly available application programming interface, which allowed access to their raw GIS (geographic information system) data. Simple analysis allowed the map to highlight relevant Native Nation’s traditional territories along the Trail, while preserving careful attention to detail. The tool used in this process was ESRI’s ArcGIS Pro.

During the creation of this map, collaboration with the team at the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) was paramount. Guidance from ATC’s GIS specialist, Josh Foster and director of outreach and education Julie Judkins allowed the creation of the map to be a seamless and enjoyable experience. Most importantly, Victor Temprano, founder of Native Land Digital, was the point person who led me to their open spatial data. GIS and cartography cannot carry out what they do without the cooperation of those who maintain data.

– Mark Hylas, A.T. Native

Lands Territory Map creator

Mark Hylas is a GIS student at Central New Mexico Community College, who originally grew up in rural New York where he was a frequent hiker of the Appalachian Trail.

For Indigenous peoples, recognizing, showing respect, and walking graciously on another people’s territory has been customary for thousands of years.

For Indigenous peoples, recognizing, showing respect, and walking graciously on another people’s territory has been customary for thousands of years. In the United States, with over 577 federally recognized tribal nations, this can take many forms. For some Native Nations there are very specific protocols that need to be abided by and heeded before one can be welcomed onto a land. This could include specific ways of asking permission, presenting gifts, or providing offerings to the land itself. For other Indigenous communities, there might be more of an informal disposition that is expected of guests as they enter into a relationship with both the people and the land they are guests upon. These types of acknowledgements do not serve any bureaucratic process but instead recognize the deep responsibility of reciprocity that is embedded throughout that landscape. It is an act of recognizing the various ways in which land provides, heals, and teaches. Lands that Indigenous people are often barred from and whose histories have been predominantly erased from these spaces.

For the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), which oversees the management and protection of the A.T. that runs through 22 Native Nations’ traditional territories, including a portion of the EBCI’s current boundary lines near Stecoah Gap in southwestern North Carolina, acknowledging the original peoples is appropriate.

A formal land acknowledgement can be one possible way to confront the legacy of displacement and genocide that led up to the creation of the A.T. As a bureaucratic, institutional practice, land acknowledgements have been practiced in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand for decades before more recently migrating into U.S. institutions such as universities, nonprofits and into art communities to name a few. In Australia, these performative acts are also known as “Welcome to Land” ceremonies, believed to be adapted from the Māori pōwhiri, a ceremony to welcome visitors that includes speeches, singing, a gift to the host and the pressing of noses (hongi). In the United States, practices of acknowledgement are often recited by a non-Indigenous person at the beginning of events, embedded within institutional documents and in some cases have multiple modes of visualizing the acknowledgement formally via posters, plaques, signage, well-crafted web pages, and other types of promotional materials.

There is no one-size-fits-all land acknowledgement as the template and language inevitably varies. However, establishing practices of land acknowledgement can be a powerful way of showing respect, countering colonial practices and narratives like the doctrine of discovery, and initiating ongoing action through reciprocal relationships. For some, acknowledgement is the first step in decolonizing institutional practices that furthers a settler-colonial agenda. Others argue still that unless there are serious conversations around land rematriation then an acknowledgement is simply a move to innocence rather than a call to action.

A portion of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indian territory boundary lines fall along the A.T. near Stecoah Gap in southwestern, North Carolina. –By Mike Waller

Acknowledgement statements can also be complicated if there are multiple Indigenous communities that claim ancestral ties to a territory. In addition, many communities historically moved from place to place, so a forced, structured territorial boundary is a colonial concept. The danger too for those looking to implement a land acknowledgement is that they become rote, sanitized, perfunctory statements that can lead to tokenizing the Indigenous peoples they are meant to show respect to. Central to a land acknowledgement statement must be a commitment to develop a deeper relationship with the various people and land the institution is attempting to recognize. Land acknowledgement truly becomes meaningful when coupled with authentic relationships and informed action. Statements should be considered living documents that evolve as relationships between communities, and also evolve with the land itself.

Fortunately, there are some tremendous online resources for those wanting to develop a land acknowledgment statement for their institution or community. Native Land Digital is a Canadian nonprofit organization that is Indigenous-led, with an Indigenous executive director and a majority Indigenous Board of Directors. They have created an interactive digital mapping project of Indigenous lands that also includes a territorial acknowledgement guide. The Native Governance Center is a Native American-led nonprofit organization located in St. Paul, Minnesota, which has created online tips for creating an Indigenous land acknowledgement. They also offer other factors to consider including thinking about who should be delivering the statement and understanding issues of displacement. The art and maps they have created around their own statement are particularly inspirational. The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture created, in partnership with Native allies and organizations, a downloadable #HonorNativeLand guide to provide step-by-step instructions on how to produce a statement and provides tips for moving beyond acknowledgment into action. In terms of how to deliver one, Laurier Students’ Public Interest Research Group provides some guidelines to follow, including providing a formal thank you to the host nation whenever making a presentation or holding a meeting, whether or not Indigenous individuals are part of the meeting or gathering.

Moving from acknowledgement to action is no easy task but a necessary first step is to begin developing meaningful relationships with the Indigenous communities that were impacted. This involves being willing to listen to the concerns and voices of the community members. What should the ATC’s responsibilities be, and to whom, as current stewards of the land? What current issues are impacting specific Indigenous communities with historic connections to Appalachian Trail land and how can the ATC be a viable partner? These might lead to uneasy and uncomfortable conversations…and that can be a good, necessary point of reflection for future generations.

For more information about land acknowledgement visit: native-land.ca

Trey Adcock

Trey Adcock (ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ, enrolled Cherokee Nation), PhD, is an associate professor of Interdisciplinary Studies and the director of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the University of North Carolina Asheville. In 2013, Trey participated in the Trail for Every Classroom program hosted by the ATC and has hiked multiple portions of the southern section of the Appalachian Trail with friends and family. In 2018, Trey was named one of seven national Public Engagement Fellows by the Whiting Foundation for his oral history work in the TutiYi “Snowbird” Cherokee Community. “I wanted to share my story and understanding of land acknowledgement outside of the general bland academic statements that have become the recent fad,” he says. “The Trail means so much to so many people I thought it was important to provide a perspective that not everyone knows or even thinks about — the daily act of land acknowledgement for Indigenous peoples.”

Trey Adcock (ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ, enrolled Cherokee Nation), PhD, is an associate professor of Interdisciplinary Studies and the director of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the University of North Carolina Asheville. In 2013, Trey participated in the Trail for Every Classroom program hosted by the ATC and has hiked multiple portions of the southern section of the Appalachian Trail with friends and family. In 2018, Trey was named one of seven national Public Engagement Fellows by the Whiting Foundation for his oral history work in the TutiYi “Snowbird” Cherokee Community. “I wanted to share my story and understanding of land acknowledgement outside of the general bland academic statements that have become the recent fad,” he says. “The Trail means so much to so many people I thought it was important to provide a perspective that not everyone knows or even thinks about — the daily act of land acknowledgement for Indigenous peoples.”

This article was originally published in the Winter 2021 issue of A.T. Journeys magazine. We are broadly sharing this and other select articles from this issue due to their important discussions on justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion, both in our work and throughout the greater Appalachian Trail community.

Discover More

Learn More

About the ATC

We are the stewards of the world’s longest hiking-only footpath, the Appalachian Trail.

Official Blog

A Deeper Connection

Embracing and encouraging a sense of belonging about the A.T., and turning that feeling into action, is the work of the A.T. Landscape Partnership.

ATC's Official Blog

A.T. Footpath

Learn more about ATC's work and the community of dreamers and doers protecting and celebrating the Appalachian Trail.