By David Field

Loving the Trail

March 11, 2022

A Life-Long Story of Stewardship

Much has been said and written about “Loving the Appalachian Trail to death.” This phrase captures the fear of the impacts that could result from overuse and/or abuse of the A.T. I share that fear, but my hope is to explain how experiencing the Trail, especially as a volunteer Trail worker, can lead to loving the Trail.

I enjoy being in the woods. As a professional forester with the United States Forest Service, I appreciated my time working in the forests of northern New Hampshire nearly every day of the year. After I returned to school for years of work that led to a doctorate and a career in forestry research and teaching, the Trail became my excuse for returning to the forest on a regular basis. My wife got used to me saying, “I need a forest fix” and tolerated my expeditions out onto the Trail, knowing that I would return home better for the experience.

I began working on the A.T. in Maine three years after Myron Avery died. I’ve slept in lean-tos built by the Civilian Conservation Corps only twenty years before and hiked many miles of the original A.T. laid out on old logging roads — something Avery later regretted. I designed and helped build more than 100 miles of the 164 miles of relocations made by the Maine Appalachian Trail Club (MATC) from 1970 to 1990, largely to leave those old roads. The exploration and discovery enjoyed during those relocation years would later be replaced by the challenges and similar pleasures of corridor monitoring. I’ve never hiked the whole Trail but have stepped on the first blaze on Springer Mountain, walked a little in each state that the Trail passes through, and climbed Katahdin many times, although only once on the route followed by the Trail.

Grounded by Care

From the start, I have been a steward of the Trail. My brother and I were assigned more than seven miles on Saddleback Mountain in Maine to maintain, beginning in 1957. The job became mine alone for many years, although I gave up a mile when I was elected to chair the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC – then known as the Appalachian Trail Conference) in 1995. In all of those years, the spring of 2015 stands out. It took me four days of chainsaw work to clear 175 blowdowns over my section. On my last trip of the year, in October, I noticed that my heart was acting a little funny. During the fall and the next spring, increasing palpitations and eventual severe heartbeat irregularity led to a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, at which point it seemed wise to reduce chainsaw work. I gave up my beloved Saddleback assignment after fifty-eight years and focused on walking corridor boundary lines in search of survey monuments.

My wife got used to me saying, “I need a forest fix” and tolerated my expeditions out onto the Trail, knowing that I would return home better for the experience.

Although I had to give up my regular maintenance assignment, I wasn’t quite through with the Trail on Saddleback. Myron Avery’s original plan for routing the A.T. across the mountain range included descending a prominent, southerly spur in the middle of the range. One of my family letters documents that, in 1860, my great and great-great grandfathers hiked up Saddleback, probably over the same route, which had been used for many years by locals to pick blueberries and mountain cranberries high on the mountain.

I first walked most of this old route on Saddleback in 2004, finding that the landowner (who preceded my brother and me as maintainers of the Trail on that section) had kept the path marked. I worked with others in 2012 to develop a route over private land, National Park Service (NPS) land, Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust (MATLT) land, and ATC land, as a proposed new side trail to the A.T. After a lengthy approval process, half a dozen of us MATC volunteers wielded chainsaws and clippers to clear the 1.7-mile route in July 2016. In August, MATLT executive director Simon Rucker (who now maintains this section) and I blazed the trail. It was signed and officially opened as “The Berry Pickers’ Trail” in September 2016. This is now a beautiful, official side trail of the A.T. Fortunately, Avery chose a final route for the A.T. in 1936 that included the rest of the Saddleback range.

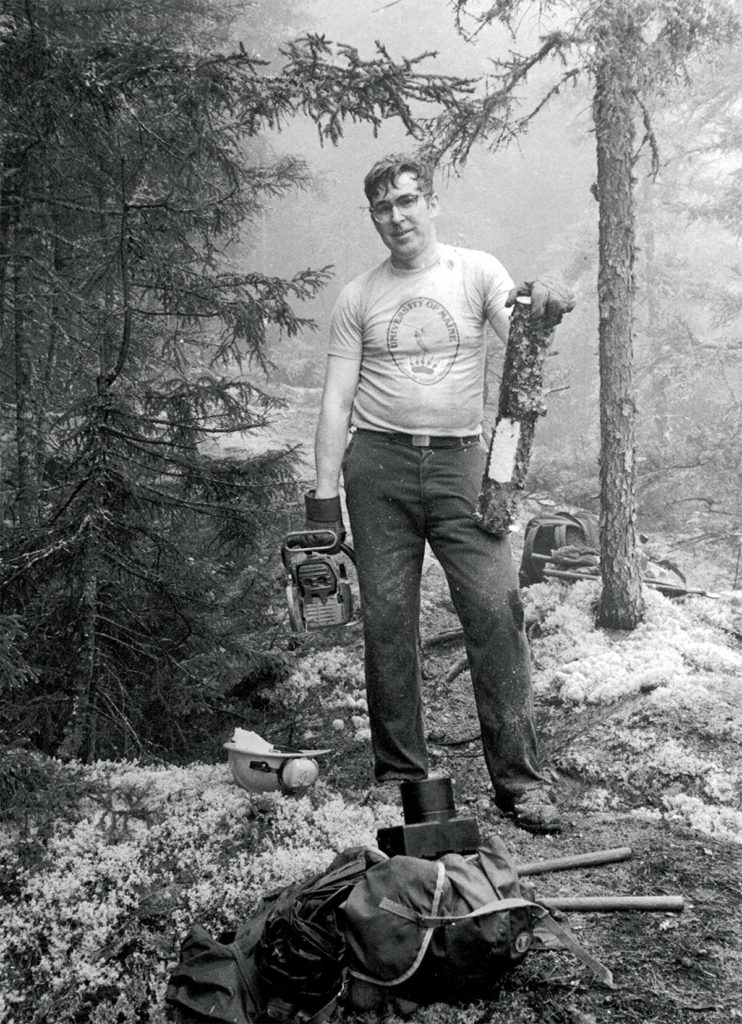

Dave Field in 1985 poses with a “rescued” white blaze while doing trail work with other MATC volunteers on the Lilly Pond relocation, east of Monson. Appalachian Trail Conservancy archives photo by Bob Proudman

A Shared Love of Land

As the MATC’s manager of lands, I relish the challenges and pleasures of walking boundary lines, and documenting monuments and witness trees. Looking for encroachments with the sixty corridor monitors whom I have trained to share in caring for the integrity of the 33,000 acres of NPS corridor lands in Maine and keeping an eye on activities on the 8,000 acres of state-owned lands along an unmarked, nominal 1,000-foot corridor through those lands is time well spent.

Of course, meeting fewer hikers is a downside of corridor monitoring. That was always one of the benefits of Trail-maintenance work. In the early years, hikers were few, and encounters were a rare pleasure. It was not unusual to spend several nights in a shelter without company other than fellow workers. In later years, thru-hiker numbers increased dramatically, and it was a delight to talk with them, learn where they were from, find out what they liked and disliked, and gather information about conditions along the Trail in Maine.

Volunteering, a sometimes unappreciated opportunity, accounts for much of my love of the Trail. I often work alone on the A.T., and personal experiences account for much of my attitude about being a volunteer: feeling good about making a favorable difference in someone else’s life; taking intense pride in the careful stewardship of an assigned campsite or section of Trail corridor; and experiencing solitude on those special days when everything combines to make that spot on the Trail where you are one of the most exquisitely beautiful places on earth.

Sharing the Trail with others sometimes takes unexpected turns. After seeing my presentation on the A.T., a forestry student at Yale University returned home to South Africa and supported the creation of a hiking trail system. Another of my Yale students helped me load a U-Haul truck with my office supplies after I accepted a job at the University of Maine. Years later, the same former student sat across the table at the office of his new employer (a major Maine forestland owner) as we discussed NPS acquisition of land for the Trail corridor. Two of my Maine forestry students, now husband and wife, monitor nearly twenty miles of exterior corridor boundary lines in Maine.

Coming Full Circle

Hiking on the A.T., at any length, must bring not only feelings of satisfaction and accomplishment but also some affection for the Trail and appreciation for the volunteers who make it possible. Volunteering, a sometimes unappreciated opportunity, accounts for much of my love of the Trail. I often work alone on the A.T., and personal experiences account for much of my attitude about being a volunteer: feeling good about making a favorable difference in someone else’s life; taking intense pride in the careful stewardship of an assigned campsite or section of Trail corridor; and experiencing solitude on those special days when everything combines to make that spot on the Trail where you are one of the most exquisitely beautiful places on earth.

A view of Saddleback Peak from the horn of Saddleback Mountain in Maine. Photo by Chris Gallaway/Horizonline Pictures

It all comes together in these moments. Talking personally with the squirrel, the moose, the chickadee whose home you are visiting, and sitting at tree line as a white-throated sparrow’s incredibly beautiful mating call unlocks decades of mountain memories. When the work is not solitary, it means laboring shoulder-to-shoulder with good people in a common cause. It is sharing a brilliant solution to a tough Trail design challenge, cutting a key shelter beam six inches too short, stuffing thousands of guidebooks and maps into little plastic bags, learning that folks from a different region can really handle a saw, as they try out each other’s techniques, philosophies, and food; and sitting together under a full moon, reminiscing and anticipating. This is how a deep love of the Trail reveals itself and then comes around full circle.

Find your opportunity to help protect and maintain the Appalachian Trail for the next generation of adventurers.

This article was first published in our Winter 2022 issue of A.T. Journeys, the official membership magazine of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

Discover More

BY SANDI MARRA, PRESIDENT & CEO OF THE ATC

A Love Letter to the Trail

ATC President & CEO Sandra Marra discusses how the relationship with her husband, Chris, was nurtured on and by the Appalachian Trail.

BY DAVID BRILL

Trail Family

David Brill shares how his Trail family merged and melded together throughout the experience of an Appalachian Trail thru-hike in 1979.

THE GREAT OUTDOORS

The Right Foundation

Derrick Z. Jackson and Michelle Holmes share how the outdoors are at the center of family, friendship, volunteering, and life well lived.