By Larry Anderson

From Trauma to Dream

October 22, 2021

MacKaye’s Troubled Path to the Appalachian Trail

Washington went down like a tent. Everything dropped. That was the real beginning of normalcy right there.” Benton MacKaye, years later, recalled the mood and the events in the nation’s capital after the November 1918 armistice that ended World War I. By then, Washington, D.C., had been MacKaye’s home and headquarters since 1911, as he worked energetically and productively for two new federal agencies, the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of Labor.

During those postwar years, the course of MacKaye’s life and career veered sharply and erratically. This period, from late 1918 through 1921, proved truly pivotal for his personal life and public legacy.

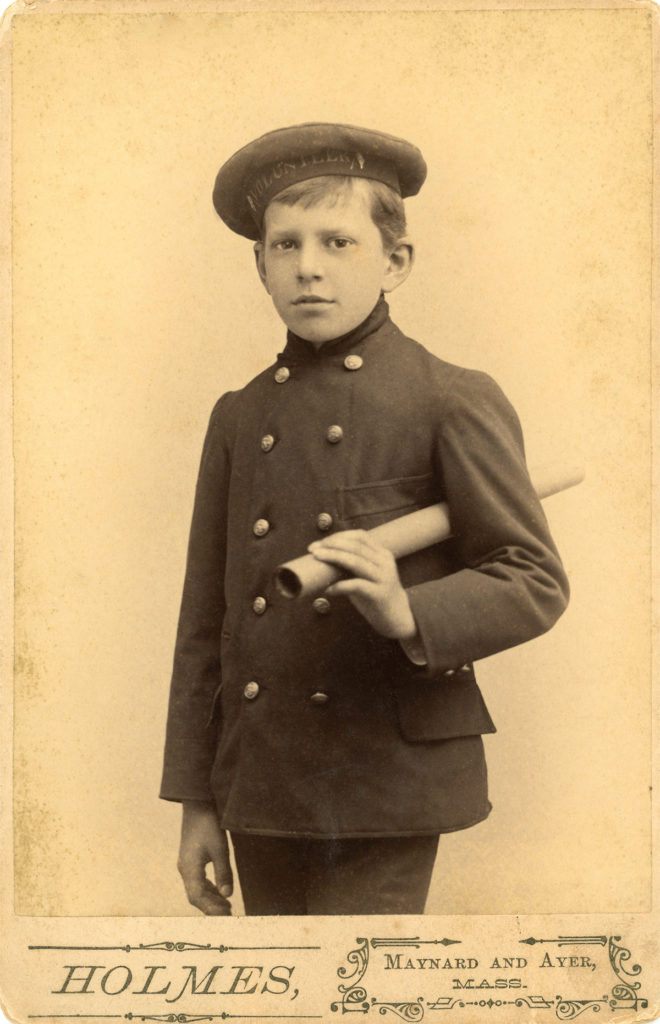

Benton MacKaye in 1889, age 10. His late-in-life admonition to “Speak softly, but carry a big map!” clearly stemmed from a very young age. Photo courtesy of the Shirley Historical Society and the A.T. Museum

His personal circumstances mirrored the tumultuous political, economic, and cultural events then roiling the nation: the Spanish influenza pandemic beginning in 1918; bitter struggles between labor and industry; racial riots, some of which led to mass killings, lynchings, and the destruction of Black neighborhoods; a roller-coaster economy, punctuated by periods of high unemployment, inflation, and housing shortages; the climax of the long crusade for women’s suffrage; a 1917 revolution in Russia and the rise of a new communist Soviet regime; and, in response, an American “Red Scare” in 1919-1920.

He quickly came under the protective wing of influential senior officials who appreciated his unique talents and perspectives and also shared some of his political inclinations. By 1915, MacKaye had begun to cooperate on projects with the recently created Department of Labor, under Assistant Secretary Louis Post; he officially transferred to that department in 1918 with the bureaucratic space to operate as essentially a freelance investigator and policy analyst.

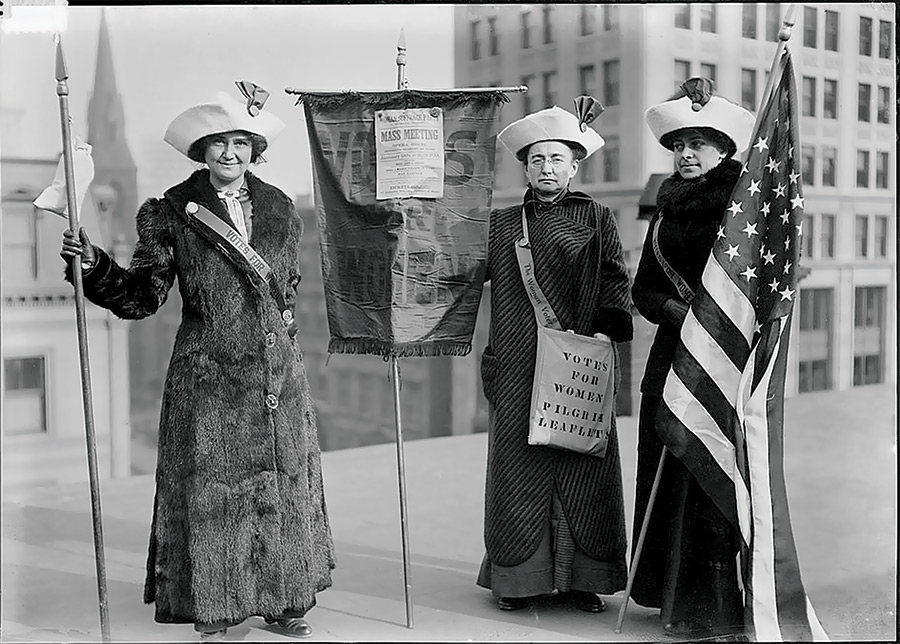

MacKaye’s personal life and activities during these years revolved around like-minded journalists, officials, lobbyists, and activists — they dubbed themselves “Hell Raisers” — who organized and propagandized for a broad variety of social and political causes. Their circle included some of the women suffragists affiliated with the militant Congressional Union (CU) led by the charismatic Alice Paul. Benton’s younger sister, Hazel, was active in the CU, which soon evolved into the National Woman’s Party.

Through Hazel, Benton in 1914 first met Jessie Hardy Stubbs, a widow and former nurse from Chicago, who had been recruited by Paul for her skills as an organizer and public speaker. In 1915, Benton and “Betty,” as she was familiarly known, were married. Both were intensely involved in their intertwined vocations and advocacy. Their respective extensive travels and busy schedules often kept them apart.

Benton and Betty joined their Hell Raising compatriots in futile opposition to American intervention in World War I. Nonetheless, when Congress in April 1917 approved a declaration of war against Germany, Benton in his official role adapted the plans and legislation he’d been developing for “colonization” to provide opportunities and employment for returning soldiers. The core of such a program called for the development of government-sponsored agricultural and forest communities on federal lands.

A young Benton MacKaye (center) hiking in New Hampshire in 1897 with Harvard friends Sturgis Pray (left) and J.W. Draper after their freshman year. Courtesy of Dartmouth College Library

The fruit of those efforts culminated in his substantial, 144-page report, Employment and Natural Resources, published in September 1919. Described by planning scholar Roy Lubove as “among the most mature and memorable fruits of the American conservation movement,” the report, illustrated with MacKaye’s stimulating maps, was a provocative work of wide range and scope. In addition to the planned farming settlements and permanent forest communities, MacKaye also described in detail ideas for a federal construction service, planned mining communities, and development of hydroelectric power and other river-development projects. The catalog of ambitious programs was ignored in the quickly changing political environment of the moment.

Publication of Employment and Natural Resources closed the first chapter of MacKaye’s career as a full-time federal employee. Funds for his position had evaporated as of the end of June, but Post helped him secure a temporary appointment with the Postal Service.

That September also marked a change in Benton and Betty’s living arrangements. They moved from their own Washington apartment to a larger rowhouse, which they shared with several of their friends and compatriots. “Hell House,” as they called their new home, was something of an experiment in cooperative living, as well as a political salon and meeting place. “The usual run of ‘reds,’ freaks, reformers, Non-Partisan Leaguers, Chinamen, et al. continue to come to us,” Benton wrote his mother, describing their lively new household.

“We are simple souls, full of busy ideas and not in a notion to fuss about the fashionables!” Betty reported to her mother-in-law from Hell House. “All of our friends are the journalist crowd who never know where the bread and butter are coming from and do not care. They are a jolly, happy group who know life and live it!” Benton looked to his friends for contacts and assistance in remaking himself as a journalist. His articles appeared in a variety of liberal and leftist magazines and newspapers.

The atmosphere at Hell House was not as carefree as Betty had portrayed it, though. Stuart Chase and another of their housemates, Aaron Kravitz, both staffers at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), were targets of a congressional investigation about their alleged socialist agenda and influence in preparing a scathing report on the price-setting practices of Chicago meatpackers. They eventually lost their FTC jobs. The specter of communist influence intensified the federal government’s efforts to root out suspected “subversives.”

Some of the Hell House residents, frustrated by national political trends and attracted to what they saw as the bright prospects of the new Soviet experiment, contemplated a more drastic response: volunteering their services to the Bolshevik government of Russia, not yet recognized by the United States. Benton, Betty, and another close Hell House habitué, journalist Herbert Brougham, met with Americans who had recently been to Russia, who introduced them to that government’s self-proclaimed American representative, Ludwig C.A.K. Martens. By late March, they had drafted a letter and accompanying résumés, which they presented to Martens. MacKaye, Brougham, and another of their acquaintances, Charles Harris Whitaker, editor of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects (JAIA), were signatories. Betty and Chase were among those who included their résumés. “Am particularly interested in the opening of new country and resources through railroad development,” Benton described his proposed work in Russia, “and in the utilization of land — farming, timber, and mineral land — so as to avoid, from the start, the needless exploitation of labor which has been the history of land concessions in America.” Martens, preoccupied with legal challenges that led to his eventual deportation, acknowledged but did not act on the proposal.

With no immediate prospects, Benton and Betty retreated to the MacKaye family refuge in Shirley Center, Massachusetts, in mid-June. For much of the previous decade, Benton had not spent much time in his beloved home territory, which he regarded as “always somewhat insulated from the dust storms of the Sahara of general life.” The rural summer interlude provided Benton an opportunity to convene with his siblings and mother to rearrange the ownership of their two modest homes, help his neighbors with haying, and, with Betty, take stock of their prospects.

Left to right: From left, the future Betty MacKaye (then Betty Stubbs), Ida Craft, and Rosalie Jones promoting a women’s suffrage mass meeting on the roof of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, thought to be taken in 1913. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On August 18, 1920, several members of the MacKaye family active in the National Women’s Party gathered at the Shirley (Massachusetts) Meeting House for a bell-ringing to mark the passage of the 19th Amendment. Mary MacKaye, Benton’s mother, is third from the right, with his sister Hazel, who worked with Alice Paul from the beginning of the movement, behind her. To Mrs. MacKaye’s right is Christy MacKaye.

In July, a new opportunity arose for Benton and Betty to reorient their lives and for Benton to reorient his career — but in new surroundings far from Washington. Herbert Brougham, whose personal relationship with both Benton and Betty was becoming closer and more complex, had recently been hired as managing editor of the Milwaukee Leader, a Socialist daily. The Leader and its long-time editor, Victor Berger, were already embroiled in controversy. Berger had served an earlier term as the first Socialist Party member of Congress, elected in 1910. He was elected again in 1918 but denied his seat by vote of the House after his 1919 conviction (later reversed) under the Espionage Act for his antiwar statements. As Benton joined the paper, Berger was once again running for Congress.

MacKaye’s personal brand of socialism, such as it was, didn’t involve him in the ideological infighting that plagued and divided the movement. He preferred to work mostly on his own or with a few trusted colleagues who understood or at least trusted his sometimes-intangible methods. Now, as a writer for a newspaper closely identified with the Socialist Party, his editorials were couched in partisan and sometimes intense rhetoric. But, Berger had a reputation as “the most conservative of all Socialists.” Benton was temperamentally attuned to the editor’s nonviolent, incremental approach to reform, based on voting, strikes, and “cooperative enterprise.” With Brougham’s guidance, Benton churned out editorials on a wide range of subjects, while hewing to the Leader’s ideological line.

Even as Benton worked long hours to find his footing as a newspaperman, his domestic circumstances remained complex and stressful. The success of the suffrage crusade represented an upheaval in the lives of the women closest to Benton — not only his wife, but also his sister Hazel and his mother, Mary. All had in some measure relied upon the National Woman’s Party (NWP) as a source of their livelihood, however meager. The NWP had also provided them a tight-knit sorority of personal support, which began to dissipate after passage of the suffrage amendment.

Hazel MacKaye, a playwright like her father and another older brother, Percy, and a women’s suffrage activist like her sister-in-law, Betty, is seen here with brother Benton during one of his visits with her at the Gould Farm sanitarium in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where she lived for nine years after a nervous breakdown in 1928. Photo courtesy of Gould Farm

In Milwaukee, Betty threw herself into the cause of global disarmament and peace. She organized a branch of the Women’s Peace Society (WPS) and demonstrated how she would exercise her newly established right to vote by declaring publicly that she had joined the Socialist Party. In October, a letter arrived from Hazel describing the plight she and her mother faced: little money, little income, no place to live for the winter. Benton, Betty, and Brougham together decided to invite Hazel and Mary to join them in Milwaukee. But, within only a few weeks, the crowded household was in crisis. Betty had alienated even some of her long-time allies in suffrage and peace activism when, at a well-attended Milwaukee rally, she had called for a “bride strike” to further the peace cause.

Betty’s provocative, elemental challenge crossed a line even for the Socialist, worker-owned Leader. Elizabeth Thomas, the paper’s president, balked at running either Benton’s editorial supporting his wife’s proposal or Brougham’s article describing the rally. Brougham promptly resigned. He and Betty were soon on a train to Chicago to promote the bride-strike campaign.

Within a few days, all five members of the unconventional household decided to return east. Betty and Brougham departed for New York City to scout for places to live and job opportunities. Benton, remaining in Milwaukee with his mother and sister, submitted his resignation from the Leader, effective at the end of December. “There is a new confident note about him nowadays,” Hazel wrote of Benton as they departed on the eve of 1921. “He frankly admits he’s found that he can write — and has a real belief in himself. That was worth coming to Milwaukee for — if for nothing else!”

Betty found the couple an apartment on West 12th Street in New York City. (Brougham now lived a block away.) She also learned of a seemingly ideal opportunity for Benton at a new nonprofit organization, the Technical Alliance, dedicated “to applying the achievements of science to social and industrial affairs.” Headed by “Chief Engineer” Howard Scott, an intense and controversial figure, the group’s small staff and organizing committee included some of Benton’s acquaintances, such as Stuart Chase and Charles Harris Whitaker. Benton immediately set to work drafting reports. In early March, he delivered his final project to Scott, who offered no additional work.

Though Benton’s prospects remained uncertain, and he was suffering from the severe intestinal symptoms that plagued him for much of his life, he immediately began, partly out of necessity, to develop some of his own proposals and ideas on his own terms. One idea in particular, which had been taking shape in his imagination since his youthful turn-of-the century hikes in the mountains of New Hampshire and Vermont, began to come into focus. “Doping out plans for Appal. trails,” he noted in his pocket diary on March 15, 1921.

The tragic events of the next months would represent the major turning point of Benton MacKaye’s lifetime. As he began sketching out plans for hiking trails and recreational communities along the Appalachian range, Betty had continued her efforts in support of world disarmament, now as legislative chairwoman of the WPS. She spoke at rallies and traveled to Washington for congressional hearings in support of a resolution calling for an international disarmament conference. The recently inaugurated President Harding met with the WPS delegation in early April, but he responded coolly. A disheartened Betty, according to her own correspondence, was considering retreating from the peace crusade.

MacKaye’s personal path to the composition and publication of his history-making, landscape-transforming article was strewn with obstacles, setbacks, and family tragedy, but that path led him to a new vocation, a new circle of friends and colleagues, and a hopeful new lease on life.

In retrospect, it is clear that the Benton and Betty MacKaye were at a personal crossroads. Rotus Eastman, a friend from the years Benton spent teaching forestry at Harvard when both he and Eastman were active in the Harvard Socialist Club, asked Benton to visit him at his Sutton, Quebec, farm, just over the border from Vermont. When he headed north on April 3, Benton was concerned enough about Betty’s state of mind to make sure that a young friend of theirs, Kathryn Lincoln, would stay with his wife.

While Benton helped Eastman gather maple sap and began his “‘larger work’ on Soc. Engin’g,” Betty, on April 6, shared the platform at a Philadelphia peace meeting with Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas. Her talk was titled “Can Women Stop War?” The weight of the world and her personal concerns were wearing her down. Upon her return to New York, she fell into deep depression.

On April 15, Benton received a letter from Betty and an urgent telegram from Lincoln and Brougham, describing her agitated state. He immediately caught a train back, arriving the next day. Two days later, April 18, Betty MacKaye was dead.

Melodramatic stories in New York newspapers recounted the moments and events preceding Betty’s death. She, Benton, and their friend, Mable Irwin, had gone to Grand Central Station to catch a train to Irwin’s home near Croton-on-Hudson, where they hoped Betty might recover. While Benton was buying tickets, Betty bolted from Irwin, reportedly exclaiming, “I’m going to kill myself” and “I’m going to end it all,” as she left the station. The accounts of what happened next, without documented witnesses, were lurid and sometimes contradictory. But, the outcome was grim and unequivocal. Betty’s body was recovered from the Brooklyn shore of the East River later that afternoon and identified the next morning by Irwin and Whitaker.

Benton would later recount her previous severe breakdown in early 1918, which might have involved a suicide attempt. “There was something wrong with her mind and that is all we know,” he wrote to one of Betty’s relatives shortly after his wife’s death.

Of all MacKaye’s unresolved emotions, his feelings about Herbert Brougham, unexpressed in any surviving records, may have been among the most confusing and troubling. In any event, except for a “good talk” a few weeks after Betty died, the two men apparently had little contact from that point on. Brougham, who later married Kathryn Lincoln, died twenty-five years to the day after Betty’s suicide.

Physically and emotionally spent himself, Benton moved in for a time with his brother Harold’s family in Yonkers. But, the direction of MacKaye’s life and career at this precarious moment was set by his friend, the generous and supportive Whitaker. Editor of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects since 1913, he and Benton came to know each other during their “Hell Raiser” and “Hell House” days in Washington. They shared a New England background as well as common political interests and aims. Whitaker was familiar with some of Benton’s specific ideas and his unique means of expressing himself.

Now Whitaker threw MacKaye a lifeline. He invited his distraught friend to spend some time at the modest farmstead he had recently acquired in the northwestern New Jersey township of Mount Olive. “Come on out and live there for a while and be my aide de camp,” he wrote. “It is grand beyond words!”

By June, Benton was spending time at Whitaker’s retreat, helping his friend with the many chores needed to make the place livable. He also plunged into an intense writing binge. A 60-page “Memo. on Regional Planning” essentially recapitulated ideas he had developed in his Employment and Natural Resources report, but with the sharper edge and rhetoric reflecting his brief stint as an editorial writer. He was using the term “regional planning” for the first time to describe his approach and what he now saw as his vocation. His vision of regional planning encompassed an alternative to the capitalist industrial system. “Given time,” he optimistically wrote, “the cooperative principle will replace the competitive one.”

MacKaye’s memo included three specific regional planning projects “with a view to securing (his) tangible employment for the regional planning in the form of a series of articles in popular magazine style.”

One project piqued the interest of Whitaker, an experienced editor, and encouraged him to take the consequential step of introducing MacKaye and his ideas to a wider circle of influential acquaintances. Benton’s proposed “Survey and Plan for an Outdoor Recreation System through the Appalachian Region” was intentionally conceived as a backdoor approach to regional planning and social reform. “In view of … the fact that outdoor recreation makes instant appeal to all classes of humans,” he wrote, “it is suggested that the most popular approach to a comprehension of regional planning might be made by presenting some big bold conception in public recreational life.”

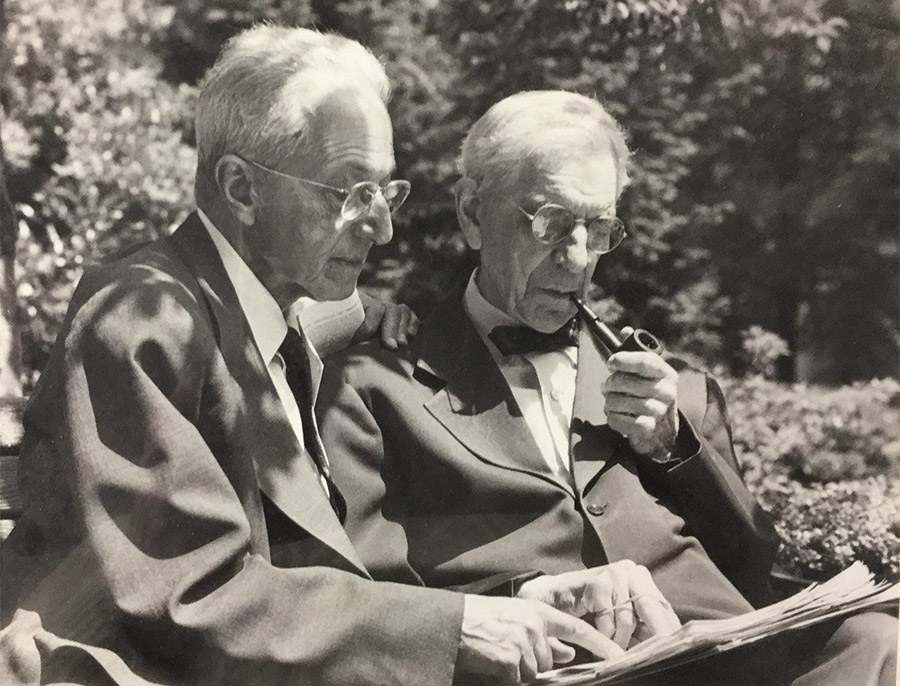

Most importantly, he described clearly and for the first time the central, connecting element of the “Outdoor Recreation System” he visualized. He proposed “the building of a ‘long trail’ over the full length of the Appalachian skyline — from the highest peak in the north to the highest peak in the south — from Mt. Washington to Mt. Mitchell.” Upon reading this memorandum on June 28, and talking it over with MacKaye, Whitaker that day wrote to another friend and colleague, Clarence Stein, about MacKaye’s work. An urbane, progressive New York City architect, Stein headed the Committee on Community Planning of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). Whitaker recognized that MacKaye’s embryonic ideas suggested a novel type of community — entirely different from anything yet conceived by urban-oriented architectural thinkers like himself and Stein.

On July 10, MacKaye accompanied Whitaker to meet Stein for the first time at the Hudson Guild Farm, on Lake Hopatcong, only a few miles from Mount Olive. Stein had designed some of the buildings at the farm, which was maintained as a retreat by New York’s Hudson Guild Settlement House. This meeting, when Whitaker offered to publish an article concerning the Appalachian recreation plan in the Journal and Stein agreed to promote it through his AIA Committee, launched the Appalachian Trail.

Clarence Stein, left, and Benton MacKaye in 1964 in the garden of Washington, D.C.’s Cosmos Club, founded by explorer John Wesley Powell, a hero of MacKaye from the time he was twelve. Appalachian Trail Conservancy Archives photo

During the next month, MacKaye adapted his memo into an article somewhat closer to the “popular magazine style” he had suggested. The JAIA, of course, was a professional journal, not a popular magazine. Nonetheless, in bringing order to Benton’s sprawling drafts, Whitaker excised words like “socialism” and “social engineering” from the published article. In that article, the forty-two-year-old author revealed an entirely original — and what has proved to be an exceptionally successful — approach to grassroots activism, conservation, and community building.

Benton MacKaye’s personal path to the composition and publication of his history-making, landscape-transforming article was strewn with obstacles, setbacks, and family tragedy, but that path led him to a new vocation, a new circle of friends and colleagues, and a hopeful new lease on life.

MacKaye never remarried. Indeed, except among his family members and oldest friends, he rarely if ever mentioned or wrote of his marriage to Betty during the rest of his long life. Not until 1981, when the archivist who catalogued MacKaye’s voluminous papers revealed that fact in a Dartmouth College Library Bulletin article, did Betty’s name and relationship to Benton become generally known.

This article was originally published in our Fall 2021 issue of A.T. Journeys, the official membership magazine of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.