by David B. Field

From Benton to Myron

October 29, 2021

The Dreamer, the Driver

Chapter twelve of Benton MacKaye’s 1928 book, The New Exploration, is entitled, “Controlling the Metropolitan Invasion.” He viewed uncontrolled expansion of development from urban centers along motorways — analogous to a flow of water from an improperly controlled reservoir — as a threat to the countryside. He envisioned a series of “open areas” along the Appalachian mountain range as a “dam across the metropolitan flood.” Motorways could still pass through, but the preserved open areas would thwart development along those routes. He felt that the developing Appalachian Trail (A.T. or Trail) “marked the main open way across the metropolitan deluge issuing from the ports of the Atlantic seaboard.” It would “form the base…for controlling the metropolitan invasion.”

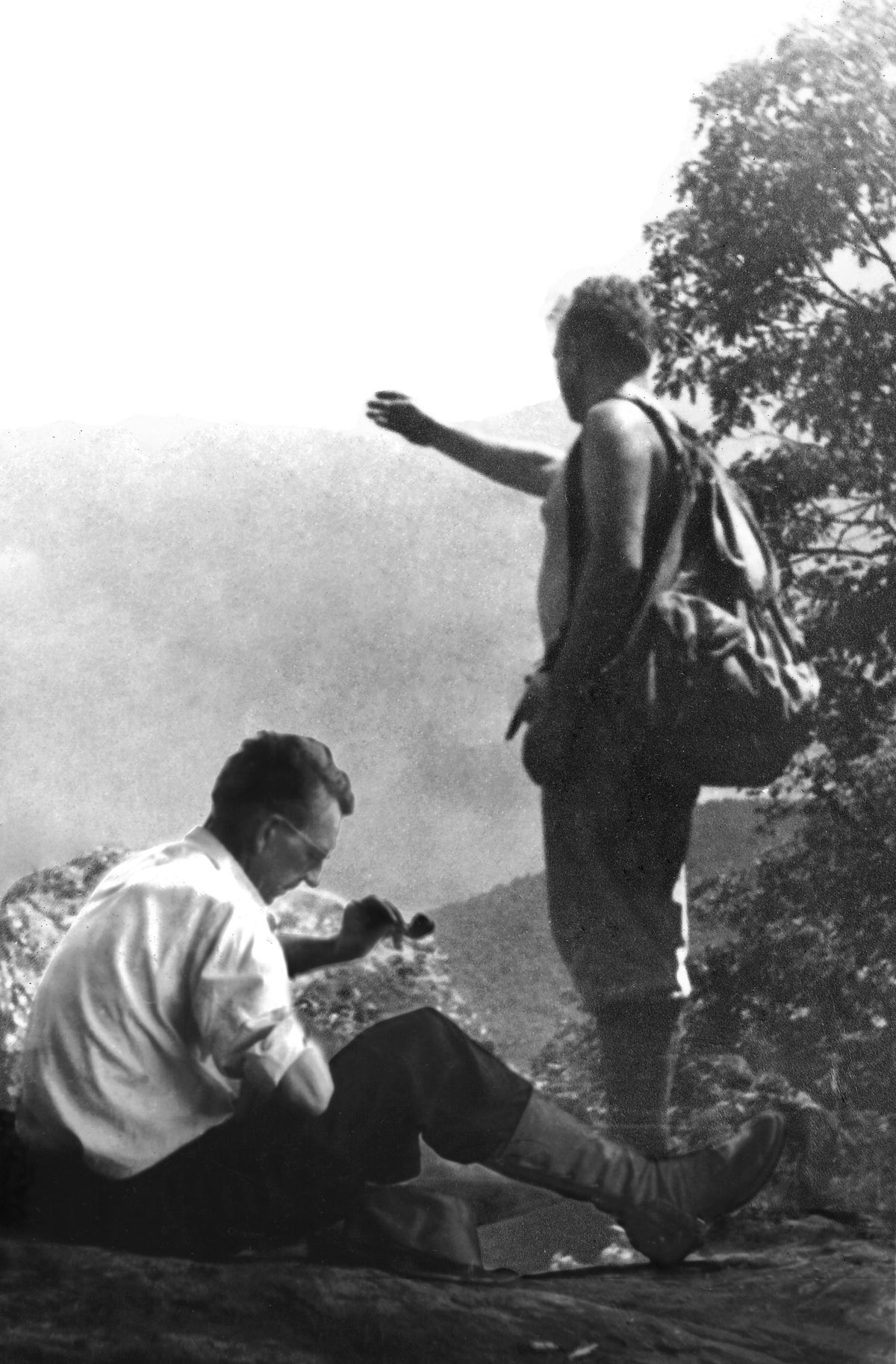

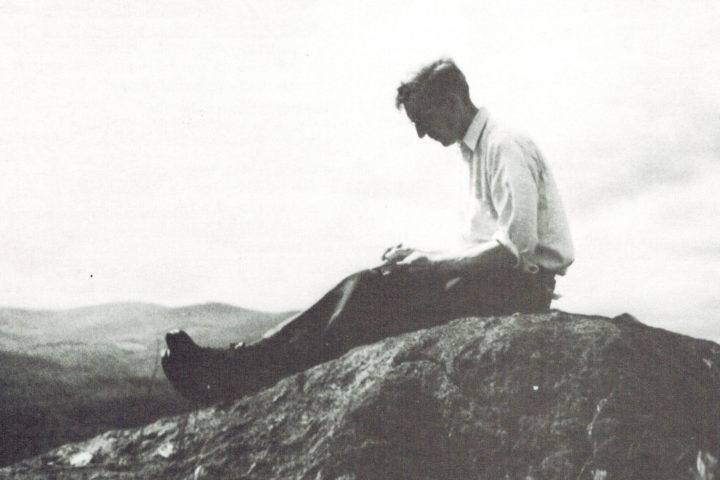

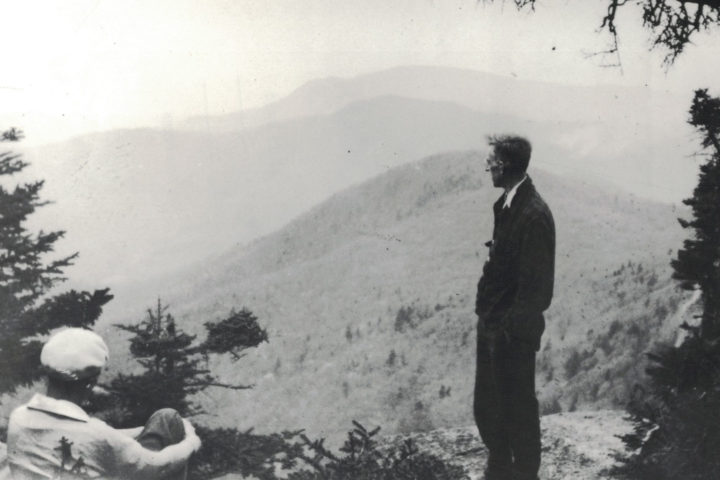

A two-photo composite. Left: Benton MacKaye reads while sitting on Eagle Rock near Jacksboro, Tennessee; Right: Myron Avery points to the horizon from Shenandoah National Park in 1938. Appalachian Trail Conservancy Archives photos

In a March 15, 1936, lecture about the A.T., Myron H. Avery stated, “A project of such magnitude, as this 2,043-mile trail, might seem to have been the result of many suggestions. It can, however, be traced very directly to one man — Benton MacKaye of Shirley Center, Massachusetts. Forester, philosopher and dreamer, MacKaye from his wanderings in the New England forests had conceived the plan of a trail which, for all practical purposes, should be endless. MacKaye also regarded the Trail as the backbone of a primeval environment, a sort of retreat or refuge from a civilization which was becoming too rapidly mechanized and developing into a machine existence.”

At that time, Avery, a founder of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), had been chairman of the Appalachian Trail Conference for five years and just become the first “2,000-Miler,” having measured all the footpath as he blazed it, persuaded others to form clubs and do the same, and then checked on them.

What did it take to translate MacKaye’s dream into reality? MacKaye was a woodsman, but Avery criticized him for focusing on the philosophy of the Trail project while seldom doing what needed to be done to bring it to fruition. Avery saw the need, not only for lobbying and building support from public agencies and private trail organizations, but also for the hard physical work of designing and scouting, marking, clearing, and then ensuring the existence and perpetuation of the volunteer groups that would maintain the Trail. Referring to Avery in a 1935 letter to MacKaye, H.C. “Andy” Anderson, a PATC cofounder and MacKaye ally who tried unsuccessfully to bring Avery and MacKaye together, wrote, “You are a dreamer and a philosopher, inclined to be fanatical, while he is a practical man, getting things done.”

MacKaye promoted the “wilderness” aspect of his dream, to the extent that he was willing to see the Trail footpath broken in places where that standard could not be achieved. Avery held to the goal of an unbroken, continuous footpath, even through surroundings that clearly bore the mark of human intrusion. The two clashed over the creation of the Skyline Drive in Virginia and its impacts on the Trail — MacKaye adamant that ridgecrest roads would destroy the “footpath of the wilderness” and Avery equally adamant that putting a complete Trail on the ground was the primary need, whatever compromises might be needed.

In his eloquent new book, From Dream to Reality: History of the Appalachian Trail, the late Tom Johnson notes, “The South was Avery’s territory.” Much of the route followed by the A.T. in the North (except for Maine) was already well-developed, but “south of the Delaware Water Gap, Avery was, alone, the undisputed leader.” Although not always the original scout, he walked every foot in the South and made routing decisions himself. After founding the PATC, “Trail scouting and marking trips began immediately that winter of 1927-1928.” With little experience in trail technique, Avery, Frank Schairer, and Andy Anderson learned as they went along how to lay out a trail from Harpers Ferry to Linden (45 miles).

Avery began a solo hike from Rockfish Gap in Virginia on June 9, 1930, carrying a heavy pack and pushing his measuring wheel. “On the evening of the third day, he walked into Camp Kewanzee on Apple Orchard Mountain, having walked and measured seventy trail miles in three days.” “In 1931, Avery travelled almost constantly.” Just before the Gatlinburg conference, he hiked the entire proposed route from Oglethorpe to Gatlinburg.

“Avery and [Paul] Fink worked together, long distance, to plan the trail route in the Smokies and, to a lesser extent, in the Nantahala, Pisgah, and Unaka forests,” Johnson wrote. Fink, an original member of the ATC board, was a pioneer backpacker of eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina and early backer of a Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Myron Avery (left), Walter Greene (in hat), Jack Dyer (back), and Frank Schairer ride the waves and dry laundry en route to the next section to flag in 1933, after installing the first Appalachian Trail sign atop Katahdin’s summit. Appalachian Trail Conservancy Archives photo

The legacy created by MacKaye and Avery combined a vision of a way to retreat from the excesses of civilization to a pragmatic goal of completing an unprecedented recreational asset that achieves that vision, in part.

Johnson notes that, in 1930, Avery observed that much of the Trail was located on private land “with the permission of the owners” — “an exaggeration because, in most cases, trail enthusiasts chose not to inform the owners.” Avery knew this but “felt it prudent to avoid the issue at the time.” He regarded formal, deeded permission to cross the many private landowner-ships crossed by the Trail as too time-consuming, opting for “handshake agreements” in most cases.

Ever the pragmatist, Avery wrote countless letters to persons who could provide him advice on routing the Trail. In Maine and some other areas, he followed four criteria: (1.) Minimize the need for cutting new trail, due to lack of volunteers and scarcity of funds for hired work. (2.) Include paths that were likely to be kept maintained for reasons other than the A.T. (3.) Involve public agency personnel in trail marking to give the Trail quasigovernment status. (4.) Locate near public accommodations.

Even the single route was not sacred. In 1935, Avery wrote to Maine’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Director James Sewall: “So, under the circumstances, I concluded that the most desirable procedure here — although we are reluctant to do it as a general matter — would be to have 2 alternative routes — both white-blazed.” Dealing with vandalism, he wrote, “It is inevitable that people should take the Trail markers as souvenirs. It simply means we have to keep replacing them. Sometimes I think it would be a good idea to put a supply at some place that is frequented on the Trail and tell people to help themselves and not have to go to the trouble of pulling them off the trees.”

Yet, in 1945, he had second thoughts about “easy” routing: “If I were locating the Trail again, I think I would keep clear of all such roads [old tote-roads], although they offer the temptation of an easy route.” “I never saw an old road grow shut the way that has in the past three years. Bushes in the road, on the side, and everywhere…To make it worse, the road is badly gullied and washed.”

Avery differed strongly with some who believed that sections of the A.T. could not be created until a local organization or organizations could be created to build and take care of it. Avery’s approach was that the Trail should first be marked on the ground and only then should its perpetuation be assured by the creation of new clubs or recruitment of existing clubs. The “Driver” focused, first and foremost, on placing the Trail on the ground.

The legacy created by MacKaye and Avery combined a vision of a way to retreat from the excesses of civilization to a pragmatic goal of completing an unprecedented recreational asset that achieves that vision, in part.

In a reverse of the original logic, MacKaye’s open-areas “dam” against the flood of civilization has become a corridor of land designed to protect the environment of the Appalachian Trail itself. The future of the Trail and the corridor will depend on sustaining the “soul of the Trail,” the volunteers who maintain and protect it, and the relationship between those volunteers and the agencies that make the Trail one of the most significant cooperative recreational projects in the history of the United States.

Going Forward

I used to ask my forestry students to imagine standing 100 years in the past and trying to predict the way things were in the present. I then asked them to look ahead 100 years and try to imagine what the world and their professional interests would be like then. There is a spruce tree behind our house that I used to decorate with lights at Christmas, without using a ladder. After 44 years, the tree is now 60 feet tall.

One thing that my students could count on was that trees would grow. But, could the trees survive climate change? Would human values for them change? Would the technologies for managing them change? Only 60 years ago, my generation of foresters saw no sign that computers, GPS, machinery, and changes in demands (such as substitution of electronic news for newspapers and magazines) would appear. When I began working on the Trail, light-weight chainsaws were unheard of. When corridor monitoring first became a regular volunteer chore, the idea of an “app” on a hand-held smartphone (to say nothing of the smartphone itself) that could show you exactly where you stood, in relation to a survey monument, would have seemed fantasy.

What do we need to think about for the future of the Trail? Let’s consider four issues:

Use: Will the future bring levels of use that the Trail cannot sustain? Social carrying capacity is often reached before physical carrying capacity. Will rationing be needed? Can rationing be done? We spend a great deal of time working on and “hardening” the Trail footpath to better withstand its physical use. Just what the tread should be is a more complex question than it used to be. Would it make a difference if the tread were “hardened” over most of its length, so long as the lands over which, and the fields and forests through which, it passes remain primitive? How much change can be tolerated before the effects are unacceptable? How much deterioration of the tread can be tolerated before the impacts are unacceptable? The trick will be finding the best balance between inadequate care and complete taming.

Volunteer Support: The United States faces an unimaginable level of public debt and a seemingly bipartisan unwillingness to pay for it. Over the years, I’ve preached that the surest guarantor of the future of the Appalachian Trail is the dedication of volunteer Trail workers — a source of productive energy and ideas that is independent of public budget fluctuations.

At the same time, the playing field has changed a great deal since the (only comparatively) simple days when Myron Avery cajoled individuals and clubs into agreeing to take care of keeping sections of the Trail clear. A well-meaning bureaucratic sense of responsibility for the welfare of Trail volunteers is leading to rules and requirements that may stifle both initiative and enthusiasm for Trail work. In all the years that I’ve been involved with the A.T., the one constant focus of volunteer distaste, if not hatred, has been paperwork. Individuals who will contribute a week of physical labor under the harshest conditions quail at the thought of having to summarize that effort in a one-page report. One of the great challenges of volunteer cultivation is the increase in paperwork that seems to be an inevitable part of the Trail’s increasing prominence.

Technology: Benton MacKaye has often been quoted as urging hikers to not simply observe what meets the eye along the Appalachian Trail but to really see what is there. “Seeing,” to this conservation pioneer, meant savoring, perceiving, understanding, appreciating, learning. This kind of Trail experience tends to vary inversely with the speed at which a hiker passes from one landmark to another. What is lost to the hiker fixated on the sounds coming from his or her ear buds?

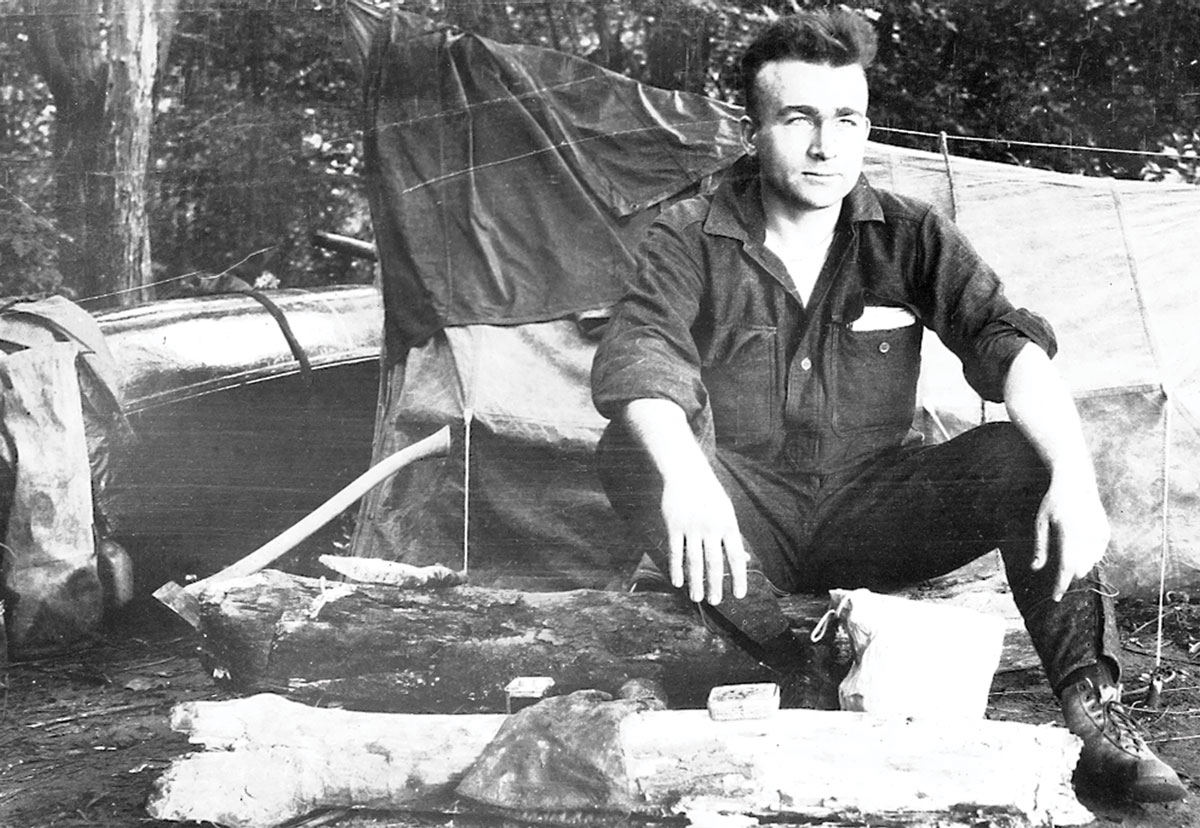

Myron Avery at camp in northern Virginia in 1927 during his first forays into blazing an Appalachian Trail. Photo from an Avery family album, courtesy of David B. Field

As he worried about controlling the physical “metropolitan invasion,” Benton MacKaye did not envision, could not have envisioned, the invasion of personal space and minds by electronic devices. Dependence on “instant communication” increasingly leads hikers to take chances on the assumption of “instant rescue.” What has the Trail experience become when those who are social-media-addicted experience anxiety when the electronic signal is not available? Will the next 100 years find a miraculous discovery that provides an electronic-free “corridor” along the Trail? I don’t see how, but I can envision a hiker ethic that encourages minimal use of such communication. Perhaps another geomagnetic storm (Google “Carrington Event”) will be needed to provide some realism and humility in this electronic realm.

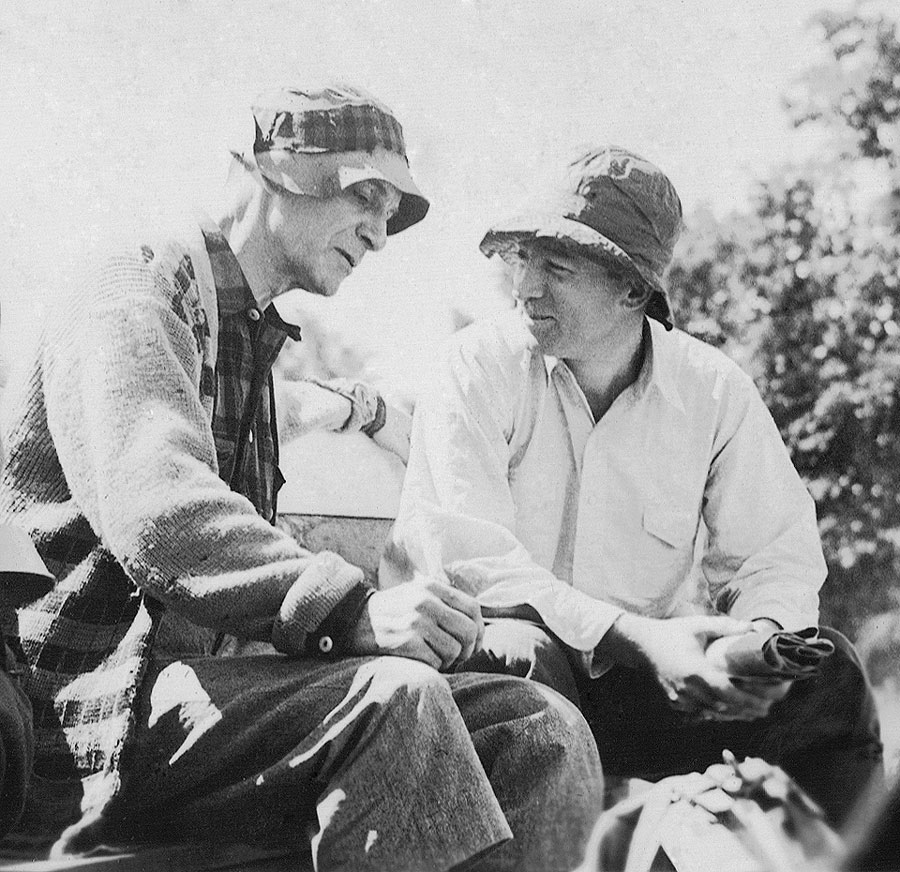

Walter Greene (left), and Myron Avery during one of their scouting and building trips in Maine. In 1933, Greene single-handedly built the Trail over Chairback, Columbus, Third, Fourth, and Barren mountains, considered by many the most rugged chain traversed by the A.T. in Maine. An article in the Appalachian Trailway News stated, “The fact that Walter Greene was 61 when he performed this herculean feat makes the project one of the great accomplishments in the annals of trail-blazing.” Appalachian Trail Conservancy Archives photo

The Trail’s Purpose: For those who will build, manage, and protect the future of the A.T., it will be important to continually remind ourselves of what the Trail is for, what it is supposed to be. “The Appalachian Trail is a way, continuous from Katahdin in Maine to Springer Mountain in Georgia, for travel on foot through the wild, scenic, pastoral, and culturally significant lands of the Appalachian Mountains. It is a means of sojourning among these lands such that the visitors may experience them by their own unaided efforts.” (Appalachian Trail Management Principles.)

In 1997, the ATC Board of Managers defined “the Appalachian Trail experience” in terms of opportunities for Trail users to interact personally with the natural and cultural elements of the Trail and the corridor. During the next 100 years, volunteers will continue to wrestle with the challenges of maintaining this experience while keeping that delicate balance between wild and safe, natural and usable, solitude and companionship, the personal Trail and the social Trail.

What is the Appalachian Trail supposed to be? “Visions of earthly beauty, the joy of contemplation in lonely grandeur and the sense of physical well-being and mental relaxation which grow out of exertion are the lot of those who follow this shining path through its somber setting,” wrote Myron Avery in January 1937. Three-and-a half years earlier, Maine pioneer Walter Greene wrote simply, “I tell you, Myron, it’s magnificent.”

Discover More

A Century of Inspiration

Benton MacKaye: Celebrating a Vision

2021 marks the 100-year anniversary of the publication of Benton MacKaye’s groundbreaking article proposing the Appalachian Trail. Even after a century, MacKaye’s original vision continues to inspire and guide us.

BY DANIEL ANTHONY HOWE

The A.T. in Its Second Century

As we celebrate 100 years since the Appalachian Trail was proposed, what will it take to conserve the Trail for another century (and beyond)?

Official Blog

From Trauma to Dream

Author Larry Anderson explores Benton MacKaye’s troubled path to the Appalachian Trail.