By Brian King, ATC Publisher

The Appalachian Trail Bill of 1978

March 18, 2018

“Protection necessary to preserve.”

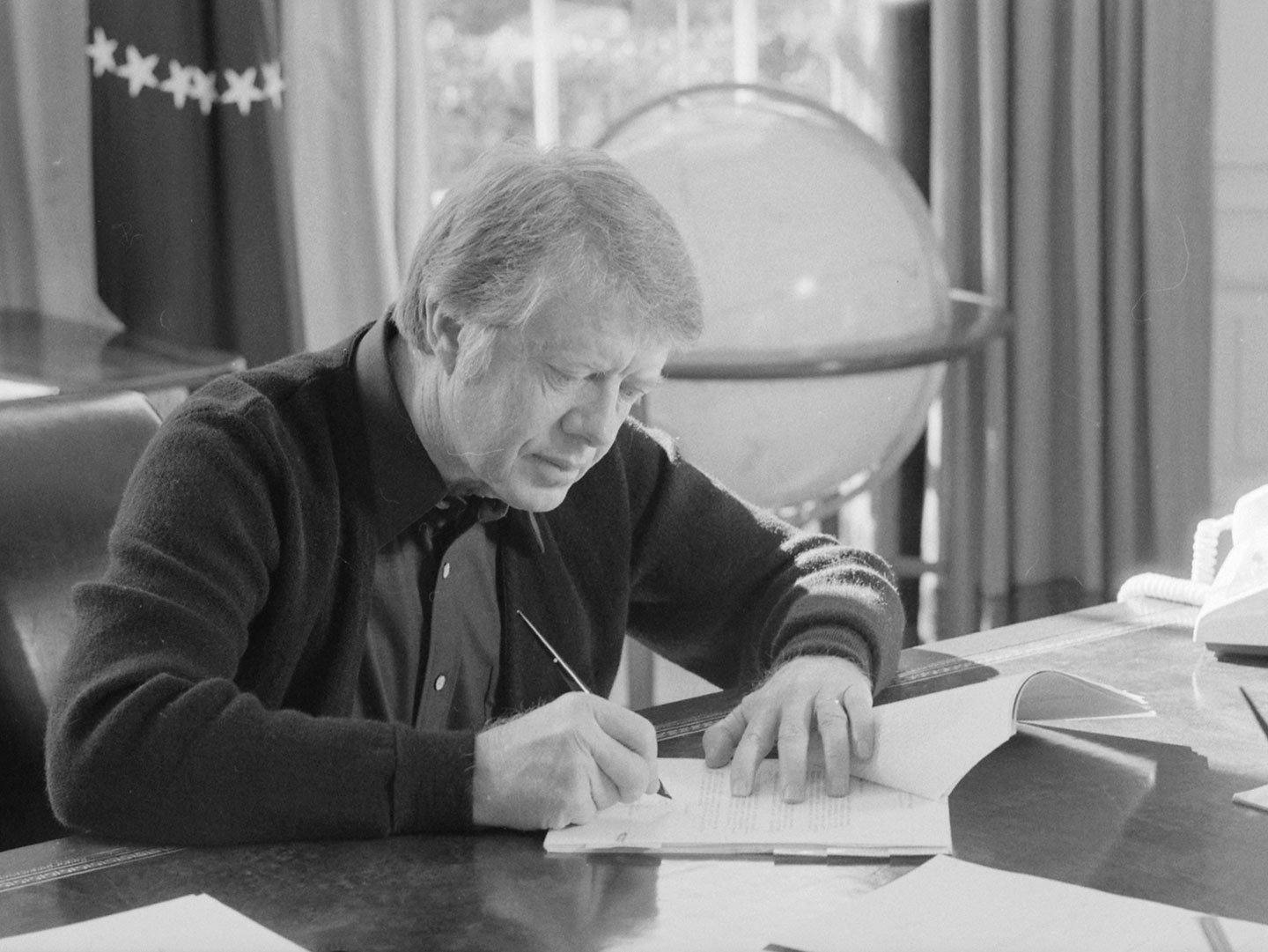

We are celebrating this year more than the arrival of spring (finally!). Every March 21, we celebrate the anniversary of a pivotal moment in the history of the Appalachian Trail (A.T.) and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC): the signing by President Jimmy Carter of H.R. 8803, “An Act to amend the National Trails System Act,” known throughout its overwhelmingly favorable legislative passage as the “Appalachian Trail Bill.”

That law, Carter said when signing it, “means that the federal government can now work more effectively with the states and citizens to provide the protection necessary to preserve — and ultimately enhance — this important part of our American heritage.” For the A.T., it put teeth in the 1968 act and pushed ATC into a new era.

In a note to ATC, Carter recalled that the A.T.’s future was “a constant concern as governor” and he made “frequent visits to the area.” As president, “I was eager to address the issue [and am] proud of the results.”

The A.T. bill:

- Told the Interior Department to move immediately on acquiring the lands necessary to provide a protective corridor for the footpath, after a decade when none of the acquisitions were authorized under the original act. Almost 60 percent of the footpath was still on private lands.

- Authorized the funds necessary to acquire those lands, which became closer to $200 million across more than 20 years than the $90 million in 3 years envisioned then.

- Required a comprehensive plan “for the management, acquisition, development, and use of the Appalachian Trail” — a “comp plan” still in effect.

- Allowed, as a last resort, the use of eminent domain for up to 125 acres per mile — which in practice meant buying a corridor averaging 1,000 feet wide, at a time when some states had acquired a mere 25-foot strip.

- Directed the ATC — a private nonprofit — to report annually to the appropriate committees on the progress of acquisitions by the National Park Service (NPS) and USDA Forest Service (USFS). The reports were to include notes on neighboring landowners’ “attitudes.”

- Led to arguably the most ambitious, complicated land-acquisition project in the history of NPS — weaving together upwards of 3,500 little strips into a linear national park when its culture was used to buying large tracts within a “square.” The chief of all NPS land acquisition quit that job to open a new office focused entirely on A.T. lands.

- Explicitly recognized the role of ATC volunteers and instructed the agencies to maintain close working partnerships with volunteer-based organizations.

Within ATC, having made the commitments implied within the legislative history, it meant a rebirth of sorts and new, focused energies and restructuring:

- Regional field offices were established as a first step in turning the ATC–club skeleton into a true, synergetic network managing the Trail, instead of just a fulcrum for occasional meetings.

- New pacts among the various state and federal partners were written. The key cooperative agreement between NPS and ATC not only governs their partnership today, but also would become the conduit for federal funds to cover about one-third of ATC’s Trail work.

- A high-ranking career USFS official was assigned full-time to help get all this on the ground and centrally cement that agency’s relationship with ATC.

- Just a few weeks into one job, new employee David N. Startzell would embark on a 34-year ATC career (ultimately more than 25 of them as CEO) focused on keeping Congress informed, keeping those appropriations coming and unifying the Trail-maintaining community.

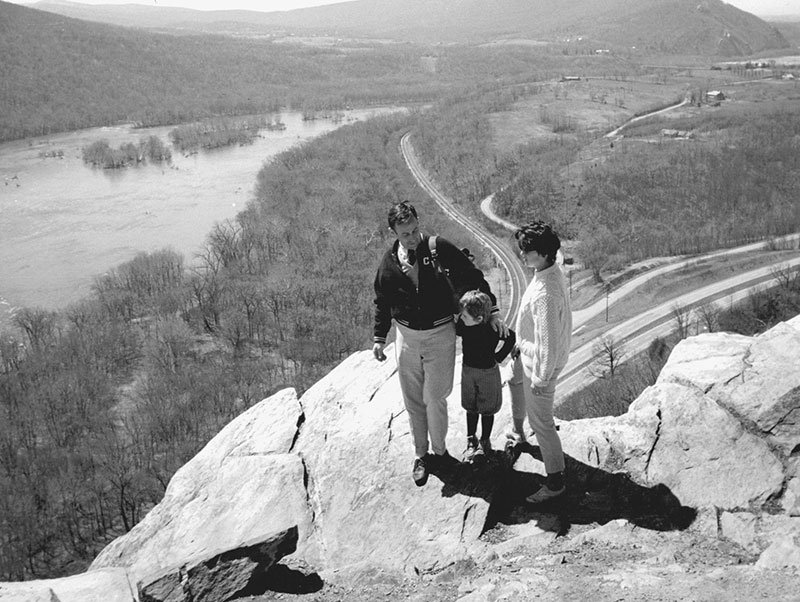

The chief sponsor of the bill was backpacking Rep. Goodloe E. Byron of Frederick, Maryland, just north of ATC’s headquarters in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The A.T. footbridge north out of Harpers Ferry across the Potomac River is named for him. Only 49 and a marathon runner, Byron died not quite seven months after the bill’s enactment — he suffered a heart attack while jogging on the C&O Canal along the Potomac.

Rep. Goodloe E. Byron and his family at Weverton Cliffs near Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

Rep. Goodloe E. Byron and his family at Weverton Cliffs near Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

Yet the force behind the bill Byron carried forward was strong, varied and persistent from 1974 on. The ATC membership meeting in Boone, North Carolina, that year nearly turned into a rage against Park Service inaction until the leader of the protest, author and Potomac A.T. Club leader Ed Garvey, was persuaded not to take it to a vote, to let the momentum gather in the shadows.

The sole NPS official assigned to the A.T. — and effectively the first NPS superintendent for the A.T. as a scenic trail — was Dave Richie, staff to an Interior advisory council that would be strengthened by the amendments. He started drafting plans and detailing the resources needed. The council, dominated by state-agency officials, energized itself and its home-state partners, such as Tom Deans of the Appalachian Mountain Club. Deans had a connection to New Hampshire Sen. John Durkin, who in 1977 called in a favor to get full Senate committee consideration and then took the bill to the Senate floor.

Just before the Carter administration took office in 1977, ATC Executive Director Paul Pritchard went over to the transition team and then to a job at Interior. His successor, Hank Lautz, developed key relationships with two congressional staffers who became lifelong assets to the A.T. project and came out for hikes between legislative tasks. Within a month, top officials began signaling their affection for the A.T.

Then, in March 1977, Carter appointed Robert L. Herbst assistant interior secretary for fish, wildlife and parks. Herbst almost immediately took up the A.T. cause with the fervor, and leadership skills, of a born-again true believer. Two months later, Herbst addressed the next ATC membership meeting with a “We will do this” stump speech. The next month, the bill was introduced by Byron.

The House overwhelmingly approved the A.T. bill with a vote of 409-12. Two months later — without objection — the bill passed the Senate in February 1978, ensuring protections for the Appalachian Trail that are clearly seen by visitors today.

For more history on the A.T., check out these books from the Ultimate A.T. Store®: