By Kim O’Connell

A Catalyst for Conservation

September 11, 2024

Sometimes a mountain is so familiar and so beloved that locals have their own name for it. Such is the case with Mount Abraham, one of the tallest peaks in Maine, which locals fondly call Mount Abram. At 4,050 feet, Mount Abraham is a familiar sight to Appalachian Trail hikers, with a rocky treeless summit that offers unending mountain views in all directions. What is harder to discern from the summit, however, is that the Mount Abraham viewshed represents a jigsaw puzzle of public and private land, which poses challenges to habitat connectivity, viewshed protection, and long-term conservation.

The view from Mount Abraham. Photo courtesy of Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust.

Thanks to a nimble new scorecard system, however, conservationists are hopeful that the land puzzle around Mount Abraham will soon become clearer. With support from the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s Wild East Action Fund (WEAF) and other sources, the Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust has developed a tool called MATGIC — Maine Appalachian Trail Geospatial Information for Conservation — which aggregates publicly available GIS data to help prioritize conservation projects.

MATGIC is a data scientist’s dream — including information on parcel size, ownership, and ecological values such as wetlands, high-elevation acreage, rare species habitat, and climate resilience, presented in a way that is easy to understand. Already, the ATC and other conservation groups both within and outside Maine are looking to use or replicate the tool to help them prioritize their own conservation efforts.

“MATGIC gives conservationists insight into a property that they might not have known about,” says Simon Rucker, executive director of the Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust. “The tool uses plain language, and it’s vetted data. We’ve had people tell us it’s very understandable.”

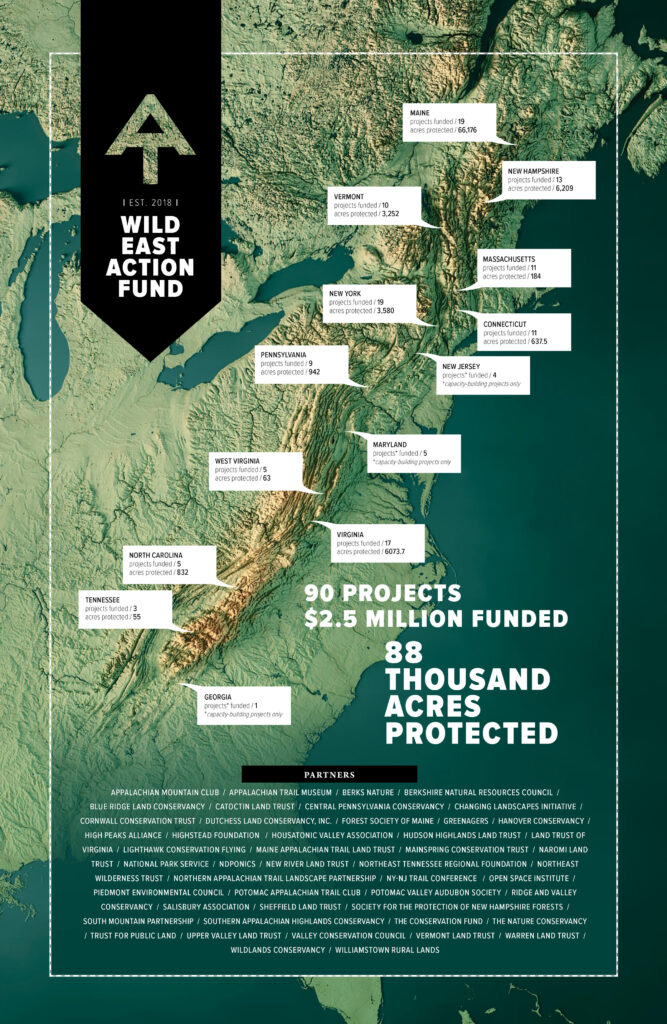

MATGIC is just one example of how the WEAF fosters partnerships and projects throughout the Appalachian Trail landscape. In the grant program’s first five years, it provided more than $2.5 million toward land protection, capacity building, and conservation planning — leading to the direct protection of more than 88,000 acres across the landscape. Funded projects range from a 10-acre plot at Calf Mountain in Virginia to 21,300 acres of forest in Grafton Township, Maine.

In the Blue Ridge region of Virginia, a Wild East Action Fund grant enabled an indigenous-led nonprofit, NDPonics, to protect a mountain peak that has been used in traditional ceremonies for generations. Photo by Lucas “Swampdog” Tyree.

“The A.T. experience is more than the treadway and the immediate corridor, and it’s impacted by a much larger landscape that the Wild East Action Fund supports,” says Max Olsen, landscape program assistant for the ATC. “The more our partners protect and manage the lands surrounding the A.T., the more we safeguard the Trail’s scenic views.”

By supporting local conservation partners doing work on-the-ground, the ATC can ensure that local conservation values and needs are met and the A.T. landscape and experience is protected. “Every community along the Trail knows what conservation means to them and how important it is,” Olsen says. “Through WEAF we can support the projects that overlap with the needs of the Trail and its greater landscape.”

In Maine, the MATGIC tool has already allowed the land trust to widen its focus to two miles beyond the federal A.T. corridor, providing a vastly broader and deeper understanding of topography, species, ownership, and more. Usually, Rucker says, conservation groups target larger parcels of land for protection — whether through outright acquisition, conservation easement, or other means — because information about them is often more readily available. But that often leaves smaller parcels out of the picture. Now, in an effort known as the Keystone project, the land trust is using MATGIC data to stitch together a collective picture of 25 smaller parcels near Mount Abraham, most just 100 or 200 acres each, that might otherwise escape notice.

By supporting local conservation partners doing work on-the-ground, the ATC can ensure that local conservation values and needs are met and the A.T. landscape and experience is protected.

“MATGIC marries this big data that is available A.T.-wide with information at the local level,” Rucker says. “With Keystone, we were able to look at all of these small parcels, and we realized that, if we add up the acreage, it’s basically a big project with high ecological value. Without this tool, nobody would be able to see that.”

A Unifying Asset

Farther south, in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, the A.T. overlooks a rich mountain and valley landscape where agriculture and development have deep impacts on the land, but also provide opportunities for creative partnerships. In this patchwork of farms and forests, WEAF grants have now funded two organizations working to conserve parcels that hold profound value both for their ecological assets and as places of traditional Indigenous knowledge.

The headwaters of Cedar Creek, well-known in Virginia as the waterway that formed the 215-foot-high Natural Bridge formation, is a province of deep forests and sheer cliffs with abiding meaning for the Yessah People. This is country that Lucas “Swampdog” Tyree, a member of the Monacan Nation, knows well: As the founder and managing director of NDPonics, an Indigenous-led organization dedicated to purchasing, preserving, and restoring lands of spiritual and ecological significance, Tyree brings multigenerational knowledge of the Blue Ridge to this work. In this landscape, his father and grandfather passed down stories about farming and foraging in the forest in ways that did not cause harm.

Now, with the support of WEAF, NDPonics owns 800 acres of this landscape. The parcel contains a key area for native brook trout and some 60 acres of wetlands, which support a critical population of glade spurge, a delicate woodland plant that is classified as vulnerable in Virginia and endangered in other parts of its mid-Atlantic range.

NDPonics is now seeking additional funding to secure an easement on the property, as well as a scholarship fund and grants to support organizations working in conservation. Supporting the site as a place of Indigenous science is especially important to Tyree. “When you say Indigenous science, it means long-term observation over generations,” he says. “Indigenous science comes from living within the landscape. It comes from patience, humility, and a lack of the illusion of dominion over the world.”

Not far away, the Valley Conservation Council (VCC) is a land trust that has both facilitated conservation easements for others and holds easements itself. VCC is now engaged in the development of its own regional data gathering and analysis tool, which allows it and its partner groups in the Shenandoah Valley Conservation Collaborative, a partnership of about 20 land trusts, nonprofits, and state and federal conservation agencies, to have a more granular landscape understanding and to prioritize conservation efforts.

The A.T. landscape is one of the most biodiverse regions of North America. The glade spurge, a delicate woodland plant is classified as vulnerable in Virginia and endangered in other parts of its mid-Atlantic range. Photo courtesy of ©Jim Stasz.

“I’m always appreciative when someone says, ‘This is a good idea; here’s some money to do it,’” says Taylor Evans, director of land protection for VCC. “The fact that the ATC recognizes that the Trail is a corridor for wildlife and people, and it’s an economic resource, really gives organizations like VCC and other conservation groups a lot of leeway to find their place in relationship to the Trail.”

Before this effort, Evans says, VCC worked to secure easements basically on a first-come, first-served basis. But now conservationists can not only take a hard look at more than one parcel at a time, they can also aggregate parcels by ownership so they can determine key individuals who might become conservation partners down the line.

“Land on the East Coast is so parcelized, with dozens and dozens of parcels sometimes owned by a single person,” Evans says. “If you know what that common ownership is, you can make huge strides towards developing those necessary relationships.”

The Appalachian Trail landscape, he adds, “is a unifying asset for so many user groups and so many conservation organizations. The WEAF is a great resource [for groups] to consider their place in this regional connection and not be afraid to pitch why their work is relevant.”

“Indigenous science comes from living within the landscape. It comes from patience, humility, and a lack of the illusion of dominion over the world.” —Lucas “Swampdog” Tyree

Fostering Partnerships

In the southern Appalachians, the Cherokee National Forest, already the largest tract of public land in Tennessee, just got a little bigger, thanks in part to a WEAF grant in 2022. In March 2024, The Nature Conservancy and The Conservation Fund (TCF) jointly announced the transfer of 54.5 acres of land in Butler, Tennessee, to Cherokee, a highly significant section of the A.T. landscape. Financial support for the project also came from the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) and other sources.

Known as the Cress Branch tract, the parcel was surrounded by national forestland on three sides and was in a pristine state, says Zachary Lesch-Huie, the Tennessee state director for TCF. “It’s probable that well over 50 years ago, it might have been logged, but it hadn’t been logged or otherwise developed in a long time,” he says. “Now this acquisition just fills the hole in this otherwise protected public landscape.”

This is critical in places like the Southern Appalachians, an area of globally recognized biodiversity that requires high levels of landscape connectivity to buffer climate change impacts as well as create corridors for plant and animal migration. Cherokee National Forest is home to several vulnerable and endangered species including the peregrine falcon, eastern hellbender, and Carolina northern flying squirrel. “It’s great if you can do one big project that protects a lot in one fell swoop,” Lesch-Huie says, “but sometimes there are small but very important pieces to protect and add.”

Funding sources like the WEAF foster not just land acquisition, conservation easements, and data collection, but partnerships throughout the A.T. corridor. “I think of it as a great big family of conservation groups that recognize each other’s strengths and interests and, when they overlap, everyone’s ready to come together and make good work happen,” Lesch-Huie says. “The private landowners should be recognized, too. Yes, they are paid, but these projects don’t happen without them. They are part of the partnership.”

Funding sources like the Wild East Action Fund foster not just land acquisition, conservation easements, and data collection, but partnerships throughout the A.T. corridor.

Funding conservation will always be a challenge, but WEAF and other sources make it easier for a broad spectrum of organizations to do their work in the Wild East. “We often can’t activate a particular project without funds like WEAF,” Lesch-Huie says. “They’re just critical for making projects happen.”

The Cress Branch project was one of the last land protection projects to be funded by the Wild East Action Fund. The grant program has been paused since 2022 due to a lack of ATC funding. In each of the five years the WEAF operated, the ATC received applications that averaged a cumulative request of over $1 million. This request far exceeded the amount of funds available and demonstrates what is needed to protect the A.T. landscape. The inspiring projects of the 47 grantees point to the creativity, commitment, and passion that partners bring to helping ensure this globally significant landscape remains connected and conserved.

“Land protection and conservation is playing a long game with a lot of hurry up and wait,” says the ATC’s Max Olsen. “Having a reliable source of private funding is essential for our partners to be efficient in the land protection game. It allows them to plan and not just react.”

In many cases, the Wild East Action Fund provided the initial funding that gave a conservation project credibility, or it gave the last critical dollars needed to bring a project to completion. “It was a true catalyst for advancing conservation priorities across the A.T. landscape,” notes Olsen, “and its absence over the past year is being felt.”

To learn more about how you can support the Wild East Action Fund, contact philanthropy@appalachiantrail.org.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2024 edition of A.T. Journeys magazine. Become a member today to help fund great storytelling about the Appalachian Trail and the community of doers and dreamers that ensure the Trail is protected forever, for all.