By Marina Richie

Wild East Time Travel

U.S. history and culture resonate throughout the Appalachian Trail and the Wild East.

Article originally published in the Summer 2019 issue of A.T. Journeys Magazine. Top image by Buddy Johnson.

Thunder reverberates. Winds gust. Ahead lies a stone shelter built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. To your right, century-old tree roots tangle among rock walls of a long-forgotten farm. Underfoot, the soils may hide an arrowhead chiseled by a hunter 9,000 years ago, or a stray bullet from the Civil War. The boulder you touch to steady yourself could well be a billion years old. You quicken your step with the urgency of all who have come before you to find refuge in a storm.

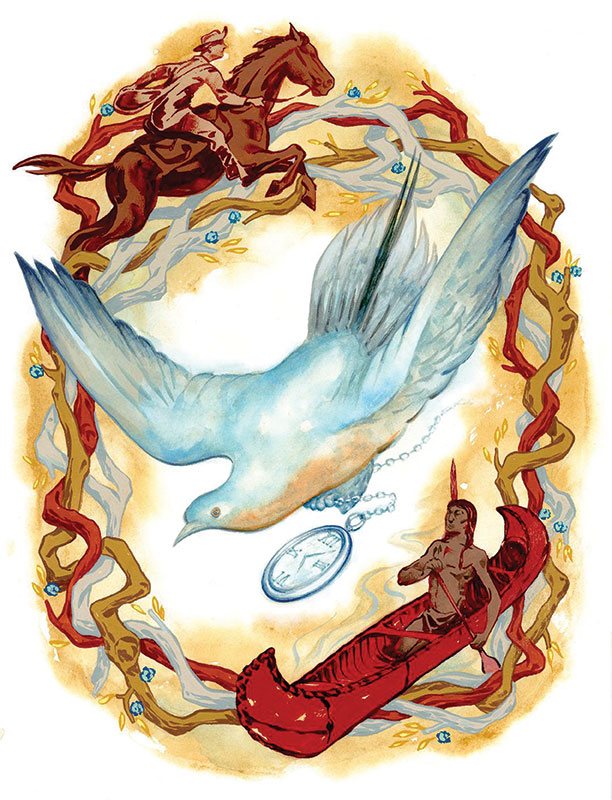

Illustration by Tim Bower

Every footfall on the Appalachian National Scenic Trail connects to the flow of human history that is anchored in geology and influenced by the north-south mountains and gaps. It is here in the Wild East when outdoors, and within the largest natural corridor east of the Mississippi River, that time travel feels possible.

As I prepare for a backpack trek across several magnificent balds this summer, I’m studying up on more than the thrushes, warblers, and vireos I hope to hear and see. I’m willing to add the extra weight of relevant history pages from the A.T. Guide to Tennessee-North Carolina, along with the A.T. Thru-Hikers’ Companion. The trick is to grasp the big picture beforehand and then study the clues and stories for each day. At the Clyde Smith Shelter, I’ll look for two rows of maple trees that signal an old driveway to a vanished homestead. Near the junction with Highway 19E, I’ll scan for black magnetic iron, leftovers from the long-closed Wilder Mine, where ten railroad cars hauled the last ore away in 1918.

When I hike over Jane Bald Summit, I’ll think of the two North Carolina sisters, Jane and Harriet Cook, and their ill-fated 1870 trek home from visiting relatives in Tennessee. Harriet fell ill with milk sickness (from cows eating a kind of snakeroot and poisoning the milk) and was too weak to walk. They spent a freezing November night on this ridge. Jane hurried for help in the morning. Rescuers brought Harriet out by wagon, but she died the next day. She was 24. Stories are sprinkled throughout the Trail. They link hikers to poignant dramas and significant historical events.

The Big Picture

Without the Appalachian Mountains, the history and culture of North America would be far different. The definitive ranges have long served as barrier, passage, and life source. Headwaters of rivers spring from cracks. Ancient rocks expose iron, coal, and quartzite. Every change in elevation hosts plant and animal life intimately tied to the mountains and in turn to the livelihoods of people. The rigor of mountain life fostered music in Appalachia, inspired poetry, myth, and fueled the indomitable human spirit seeking the solace of, and the sacred in, high places.

Some 480 million years ago, the buckling, folding, and faulting of colliding continental plates defined violent beginnings, perhaps a prelude to what would come much later in human conflicts. Once, the Appalachians jutted skyward as high as the Himalayas. Over the millennia, a series of mountain building events shaped the ranges of today. Erosion gentled and lowered the summits, yet there are no shortage of steep ascents, rocks, and roots interspersed with the bliss of ice-cold springs, waterfalls, sheltering forests, wildflower meadows, and the gaps between high points that played a vital role in human history.

Each December, the Annual Antietam National Battlefield Memorial Illumination in Maryland takes place to honor those soldiers who fell during the Battle of Antietam with 23,000 candles — one for each soldier killed, wounded, or missing at the Battle of Antietam. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

From Georgia to Maine, the A.T. traverses history — not in straight lines, but more like skipping stones. In New York, cross the Bear Mountain Bridge on the Hudson River and feel the icy retreat of glaciers that carved the valley. Listen for the ghostly echoes of gunshots fired by Revolutionary soldiers from hillsides, the splash of oars a century earlier when Dutch settlers headed to the interior to farm the highlands, and the almost silent paddles of Native Americans slipping up and down the river as they had for thousands of years before European arrival.

Barrier

For the tribes that flourished before European arrival, the Appalachians were not a barrier, but part of the seasonal round that offered good hunting and gathering. However, they concentrated their villages and agriculture in the fertile valleys and at the confluences of rivers. Hikers on the A.T. can cross homelands of first nations that include the Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Abenaki of New England. The Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Mohawk and Tuscarora all united as the Iroquois confederacy in New York. Pennsylvania is home to the Lenape and Susquehannock, and to the south, the Cherokee formed the largest of the Appalachian tribes.

For white settlers from the sixteenth to seventeenth centuries, the daunting march of Appalachian Mountains formed a physical obstacle, and then a mystical frontier between the Atlantic and the wonders of the West. The arrival of some 200,000 Scotch-Irish from 1710 to 1775 marked a push into the spine of the Appalachians. Initially, they sought cheap land and a new life in New Hampshire and Maine. Many moved on to Pennsylvania and others to the southern mountains, giving rise to the music and culture of Appalachia. Another barrier appeared in the clash of cultures as the Scotch-Irish intruded upon the tribal homelands, contributing to tragic episodes in mountain history. None are more infamous than the Cherokee Trail of Tears that followed the 1830s Indian Removal Act.

In 2016, seven African Americans re-traced the historical route of the Underground Railroad along a 40-mile stretch of the A.T., from the Mason-Dixon line south to Harpers Ferry. Equipped with high-tech backpack gear, the hikers still shivered in torrential downpours as they envisioned the hardships and life-threatening dangers of fugitives from slavery. Outdoor Afro, the oldest black-led conservation group, organized the trip. Photo courtesy of Outdoor Afro.

By the twentieth century, the high peaks and ridges would pose a literal barrier for pilots in bad weather. German balloonists crashed in high winds on Thunder Hill on Virginia’s Blue Ridge during a 1928 race, and survived. In New Hampshire, a Northeast Airlines plane struck a ridge below Moose Mountain, killing 32 of 40 on board. Audie Murphy, World War II hero and actor, died when the small plane smashed into Brush Mountain near New Castle, Virginia in 1971, marked by a trailside monument. Since 1920, more than 55 planes have crashed in what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, including an Air Force Phantom jet that slammed into Inadu Knob in 1984. Fragments are still visible from the Trail.

Passage

Every gap, notch, or valley between mountain ranges signals a passage for animals and people alike. Once plentiful until the mid-1700s era of plunder, eastern buffalo funneled through the Blue Ridge’s Bearwallow Gap, also an ancient Native American route. Can you hear their ghostly snorts and pawing hooves in the winds? The major gaps funneled transportation routes, from trails to railroads to highways.

In times of war, the gaps proved strategic places to defend. During the Civil War, Confederates and Union forces sought to control access to the Shenandoah Valley — both for its resources and as a thoroughfare for supplies and regiments. Three gaps on the A.T. in the Shenandoah National Park section proved pivotal for the Confederates in 1862 — Browns, Rockfish, and Swift Run Gaps.

In that same era, beginning in 1851, slaves seeking freedom navigated a mountainous route near or on today’s A.T. to cross the Mason-Dixon line into Pennsylvania. Most of the Underground Railroad routes likely followed the more forgiving mountain flanks.

Where the Cherokee Trail of Tears Intersects the A.T.

A sign marks the intersection of the Trail of Tears historic route and the A.T. at Nantahala Outdoor Center. Photo by Kristina Moe.Where A.T. hikers and paddlers converge at the Nantahala Outdoor Center, only 181 years ago Cherokee families hid in laurel thickets to evade captors. The U.S. military forced most of the 17,000 Cherokees and four other tribes to march to Oklahoma reservations in 1838-39. At least 4,000 died of hunger, cold, and disease. Today, the Trail of Tears is a national historic trail covering 5,000 miles of routes west.

A sign marks the intersection of the Trail of Tears historic route and the A.T. at Nantahala Outdoor Center. Photo by Kristina Moe.Where A.T. hikers and paddlers converge at the Nantahala Outdoor Center, only 181 years ago Cherokee families hid in laurel thickets to evade captors. The U.S. military forced most of the 17,000 Cherokees and four other tribes to march to Oklahoma reservations in 1838-39. At least 4,000 died of hunger, cold, and disease. Today, the Trail of Tears is a national historic trail covering 5,000 miles of routes west.

In October of 2018, members of the Eastern Band of Cherokees gathered with partners from the Trail of Tears Association, and NPS staff from that national historic trail, and the ATC to dedicate North Carolina’s first Trail of Tears historic marker at the Nantahala Outdoor Center’s junction with the A.T. One arrow points five miles to Fort Lindsay, where soldiers rounded up the mountain Cherokees, and the other arrow points 895 miles to Woodhole’s Depot in Oklahoma. The Museum of the Cherokee Indian, in nearby Cherokee, North Carolina, is dedicated to “preserve and perpetuate the history, culture, and stories of the Cherokee people.”

Life Source

The Appalachians have long sustained life, from rivers and forests to wildlife, plants, soils, and arguably the human soul as well. The thirst-quenching springs are natural places for camps dating back thousands of years. A flat spot nearby to sleep, shelter from wind, and southern exposure would add even more attractive qualities. Later, moonshiners would build whiskey stills by certain springs, especially if not far from corn, rye, and wheat ingredients.

Trickling springs converge into streams and then mighty rivers. The New River, coursing 320 miles from the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina is one of the world’s oldest. About 300 to 270 million years ago, continental collisions formed the supercontinent Pangea and, as they shoved masses of rock into mountains, the river system lifted with them.

The high elevations in turn offered a corridor for northern forests to expand far southward, and for the great migrations of birds catching updrafts and finding shelter. Those natural qualities persist in the Wild East, along with the relics of logging, clearing the woods for farms, fuel, and war. Awe-inspiring primeval forests remain in pockets and within the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, saved from the saw by the rugged terrain and the foresight of early conservationists. There’s a renewal story, too, in the returning forests and in our evolving relationship with trees, valuing them for storing carbon, anchoring watersheds, hosting wildlife, and nurturing the human spirit.

National Historic Treasure

Step back and consider the sheer quantity of history and culture resonating along the 2,191 miles of Appalachian Trail. The National Park Service-led surveys in 2002 and 2009 listed shelters, Civilian Conservation Corp camps, viewpoints, roads, bridges, buildings, monuments, fire towers, railroad grades, and moonshine stills to tally more than 1,200 features. The list goes on from prehistoric sites to quarries, kilns, and mines of early industry that gave way to richer prospects west.

A marble slab monument on the A.T. in Massachusetts marks the last battle of Shay’s Rebellion. Photograph courtesy of Jordan Bowman.

Why does the A.T. harbor so many clues to our past, and so many opportunities for time travel? Volunteer Trail clubs deserve immense credit for maintaining Civilian Conservation Corps-era rock walls, steps, cabins, shelters, and fire towers. Hikers contribute by practicing Leave No Trace ethics to prevent vandalism, litter, and removal of historic artifacts. The more than 40 recognized Appalachian Trail Communities are leaders in geotourism that sustains our natural and cultural heritage. They support museums, exhibits, and culture that in turn enrich the hiking experience.

Ultimately, we owe the plethora of historical treasures to Benton MacKaye and his 1921 vision for the creation of a footpath along the eastern U.S. We also owe those gifts to Arthur Perkins and Myron Avery whose early efforts led to the completion of a marked A.T. in the 1930s. Skip ahead to the National Trails System Act of 1968 that designated the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, creating a holistic park and jump-starting an ambitious project to acquire and preserve the Trail within a publicly-owned corridor. That effort is 99 percent complete. This is the “People’s Trail,” where volunteers make the difference, everyone shares credit, and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy leads with the National Park Service as partner, along with other agencies like the U.S. Forest Service and local community members in the 14 states. The journey of protection is far from over, as new threats emerge along with a recognition of the need to expand conservation efforts for a wider and more buffered Wild East.

The next step? Historians hope to see the entire A.T. added to the National Register of Historic Places, offering more protection from development, funding for restoration, and greater public appreciation.

For my own small journey on the A.T. this summer, I’m feeling inspired to hike with greater attentiveness to layers of history and the stories floating on the breeze, conveyed in the bird songs, shining down from brilliant stars, and stirring among untended apple orchards merging with wild forests. I believe if you want to time travel, you need to remove yourself from the hustle, noise, and technology of our modern society. There’s no better place than within the Wild East and the lifeline of the Appalachian Trail.

After a deep dive into history, Marina Richie has a piece of advice for fellow hikers: If you want to time travel, pause to touch a boulder and feel the passage of human history grounded in geology and shaped by the north-south mountain range.Marina often writes about the confluence of nature and culture, and authored the winter 2019 feature, Wild Skyway.

“Researching this piece offered new and often emotional insights into the Cherokee Trail of Tears, and those who traversed the Underground Railroad, as well as stories from the Revolutionary and Civil wars, and the CCC-era,” she says. “The sheer magnitude of historical events converging with the A.T. challenged me to find the common thread of the mountains and gaps as barrier, passage, and life source.”

Discover More

By Marina Ritchie

Wild Skyway

Wherever you are on the Appalachian Trail, birds offer sweet companionship. Yet, as hiker numbers soar, bird populations tumble.

By Jennifer Pharr Davis

Scenic Views

Wide-open vistas beyond the footpath offer respite and are essential to the Wild East.

Roan Highlands Haven

Appalachian Balds are for the Birds

The iconic bald mountains along the Appalachian Trail in North Carolina and Tennessee are significant to the future of migratory and resident birds.