Learn More

Health

Hiking the Appalachian Trail (A.T.) can do wonders for your overall health. But spending time in nature requires special preparations to stay healthy when you’re away from civilization.

Tick-Borne Diseases

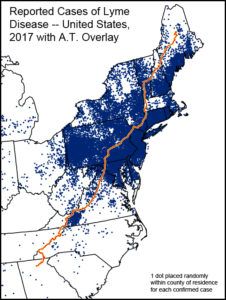

The greatest risk to your health and safety while hiking the Appalachian Trail is contracting a tick-borne disease.

The greatest risk to your health and safety while hiking the Appalachian Trail is contracting a tick-borne disease.

As of 2019, multiple species of ticks can be found in every one of the 14 states that the A.T. passes through.

Although Lyme disease, carried by the deer tick (also known as the black-legged tick) is the most common, there are several tick-borne illnesses present on the A.T. Combinations of diseases may occur from a single tick bite. Although tick-borne illnesses are usually quite treatable, symptoms can be severe and long-lasting, and a few of the less common ones can be life threatening, especially for those with compromised immune systems if not treated promptly.

For comprehensive information about tick-borne illnesses and symptoms, click here.

The characteristic “bulls-eye” rash sometimes occurs with Lyme disease, but not always. Symptoms that may indicate tick-borne illnesses and a need for medical attention include flu-like symptoms such as fever, chills, headache, joint pain, muscle aches and fatigue. For many tick-borne illnesses, symptoms may continue for months or even years and treatment may be difficult. Treatment is most effective immediately after a tick bite.

Most humans are infected by nymphs, which are about the size of a poppy seed and difficult to see. The most common time of year to be bitten by a tick is from May through July, but you can potentially be bitten by a tick any time of year, even in cold temperatures.

Most humans are infected by nymphs, which are about the size of a poppy seed and difficult to see. The most common time of year to be bitten by a tick is from May through July, but you can potentially be bitten by a tick any time of year, even in cold temperatures.

Prevention is the best strategy! Your chances of being bitten by a tick can be greatly reduced by taking these precautions:

- Wear clothing treated with permethrin (kills or repels ticks on contact). At InsectShield.com, you can purchase pre-treated clothing, buy spray to apply to clothing yourself, and/or send in your own clothing to be factory-treated. Use promo code “ATC” for a 15% discount on your first purchase. In addition, 10% off all sales purchased through these links will be donated back to ATC.

- Treated trousers or bug-net pants over shorts are very effective and the bug-net pants allow for ventilation on warm, humid days. Wear long pants tucked into socks, and shirt tucked into pants (ticks crawl up); long-sleeved shirts, especially when treated with permethrin, offer more protection than short sleeves.

- Spray-on permethrin can also be used to treat your pack and outer tent floor.

- Wear light-colored clothing; ticks can most easily be spotted against a lighter color.

- Use insect repellent that contains 20 to 30 percent DEET or picaridin on exposed skin.

- Check for ticks frequently. Removing an embedded tick as soon as possible reduces risk of illness.

- Use fine-tipped tweezers or a tick key to lift under the mouthparts in a slow, steady pull.

- Choose areas and times of lowest risk. Ticks are generally found in areas under 2000-2500′ elevation, and most cases are reported from May through July, when nymphs are active. States from Virginia through Vermont have the highest incidence of Lyme disease. However, Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses can be contracted in any A.T. state at any time of year.

- Avoid sitting directly on the ground or logs; sit on a pad treated with permethrin instead.

- Once inside, put clothes in the dryer on high heat for 60 minutes to kill any remaining ticks.

- Check your body for ticks after being outdoors. Conduct a full body check upon return from hiking. Use a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body. Check these parts of your body and your child’s body for ticks:

- Under the arms

- In and around the ears

- Inside belly button

- Back of the knees

- In and around the hair

- Between the legs

- Around the waist

- Shower as soon as possible after being exposed to ticks; showering within two hours of coming indoors has been shown to reduce your risk of getting Lyme disease and may be effective in reducing the risk of other tickborne diseases. Showering may help wash off unattached ticks and it is a good opportunity to do a tick check.

- Consider leaving your dog at home. If you are hiking with a dog, keep in mind they will attract ticks and can put you at a higher risk for coming in contact with them. Be sure to check your pup as often, if not more often, than you check yourself.

For an in-depth article about Lyme disease on the A.T., click here.

Bit by a tick on the Appalachian Trail?

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has an interactive Tick Bite Bot that can guide you on removing attached ticks and help you determine when to seek health care, if appropriate, after a tick bite.

Sanitation

Although you will get dirty backpacking, it shouldn’t be an unsanitary experience. Flush toilets and showers don’t exist on the A.T., but you can still prevent the spread of norovirus and treat blisters to prevent infection.

Restrooms

Don’t expect flush toilets on the A.T. Most A.T. shelters have privies, but often you will need to do your business in the woods. Proper disposal of human (and pet) waste is not only a courtesy to other hikers, but is a vital Leave No Trace practice for maintaining healthy water supplies in the backcountry and an enjoyable hiking experience for others.

Don’t expect flush toilets on the A.T. Most A.T. shelters have privies, but often you will need to do your business in the woods. Proper disposal of human (and pet) waste is not only a courtesy to other hikers, but is a vital Leave No Trace practice for maintaining healthy water supplies in the backcountry and an enjoyable hiking experience for others.

No one should venture onto the A.T. without a trowel or a wide tent stake, used for digging a 6- to 8-inch deep “cathole” to bury waste. Keep in mind the following guidelines when pooping in the woods:

- Bury feces at least 200 feet or 70 paces away from water, trails, or shelters.

- Use a stick to mix dirt with your waste, which hastens decomposition and discourages animals from digging it up.

- Used toilet paper should either be buried in your cathole or carried out in a sealed plastic bag.

- Carry out all trash such as pads, tampons, and wipes (even those marked as biodegradable or compostable) – they do not decompose in cat holes or privies.

- Use soap and water to wash your hands well away from water sources; hand sanitizers kill some germs but are not as effective against norovirus.

Pooping Like a Pro on the A.T.

Learn more about properly disposing of human waste on the A.T., which will help protect the Trail, volunteers, other hikers, and wildlife.

Showers

Showers are rarely available right on the A.T. Hikers usually shower while at hostels or hotels in towns; less common are campgrounds with shower facilities.

Showers are rarely available right on the A.T. Hikers usually shower while at hostels or hotels in towns; less common are campgrounds with shower facilities.

To bathe in the backcountry, carry water 200 feet from the water source in a container and rinse or wash yourself away from streams, springs and ponds.

Blisters

Blisters are one of the most common ailments suffered by hikers. Not only can they be painful and take the fun out of hiking, but they can be an entry point for infections, which can be serious.

Blisters are one of the most common ailments suffered by hikers. Not only can they be painful and take the fun out of hiking, but they can be an entry point for infections, which can be serious.

To help prevent blisters, break in new shoes or boots gradually before you begin your hike. As soon as you feel any discomfort or “hot spot” developing, stop hiking and place moleskin or duct tape over areas developing soreness.

- Keep your feet as dry as possible while hiking.

- When you stop for breaks, take your shoes and socks off to air out your feet or change socks.

- Don’t wait for a blister to develop before treating.

If a blister does develop and breaks, or is painful enough that it needs to be popped to reduce pressure, use a sterilized needle to puncture the blister. Clean and disinfect the area, apply antibiotic ointment, and cover with an adhesive bandage or blister care product. A couple layers of moleskin with a circle cut out just larger than the blister, or donut-shaped adhesive-backed callous cushion can relieve pressure.

Remember this advice: keep blisters “CDC,” or Clean, Dry, and Covered. Click here for a poster!

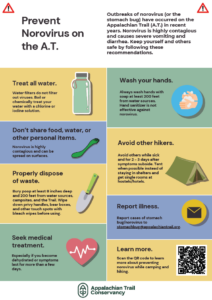

Norovirus

Norovirus, a highly contagious stomach virus, is transmitted by contact with an infected person, contaminated food or water, or contaminated surfaces, and it is easily spread on parts of the A.T. that experience crowded conditions. Norovirus causes your stomach and/or intestines to become inflamed, which leads to stomach pain, nausea, and diarrhea.

The virus has a 12- to 48-hour incubation period and lasts 24 to 60 hours. Infected hikers may be contagious for three days to two weeks after recovery. Outbreaks occur more often where people share facilities for sleeping, dining, showering, and toileting; the virus can spread rapidly in crowded shelters and hostels; and sanitation is key for avoiding and spreading norovirus.

Take the following steps to prevent contracting and spreading the illness:

- Do not eat out of the same food bag, share utensils, or drink from other hikers’ water bottles.

- Wash your hands with biodegradable soap (200 feet from water sources) before eating or preparing food and after toileting.

- Be aware that alcohol-based sanitizer may be ineffective against norovirus.

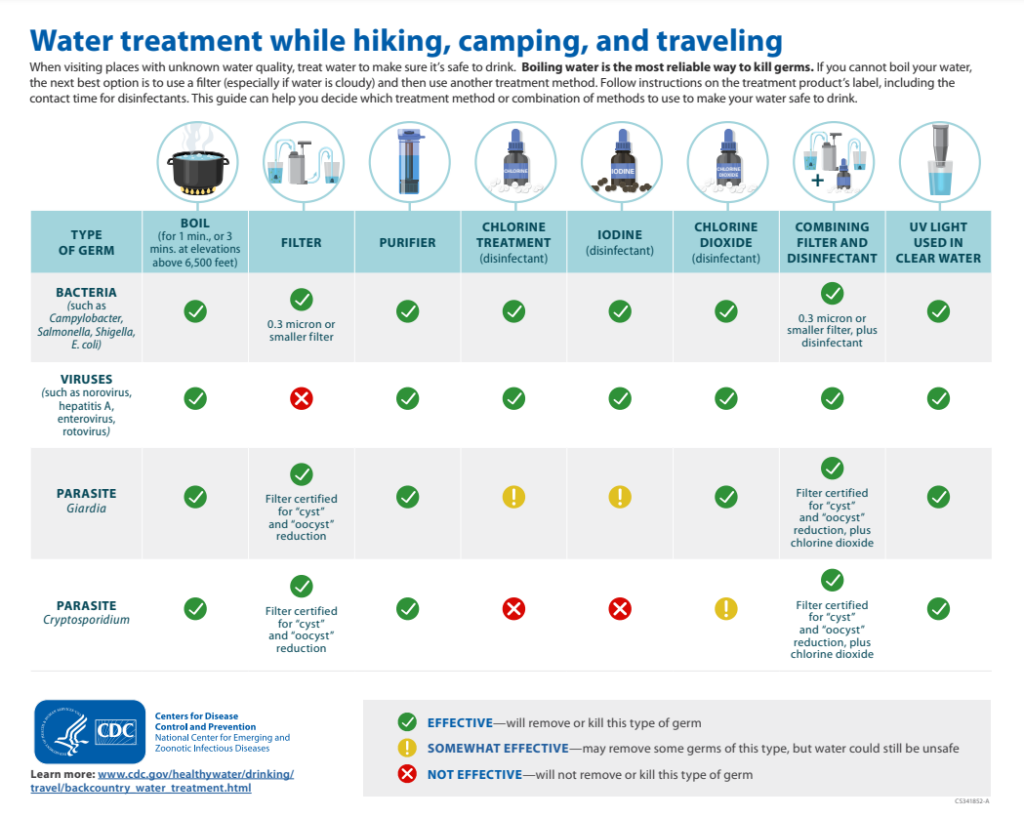

- Treat all water. Filters do not get rid of viruses. To learn best how to treat your water, click here for information from the CDC.

- Follow Leave No Trace guidelines for disposing of human waste.

Learn important prevention tips and information about how to report norovirus on the Appalachian Trail and download this Prevent Norovirus Poster.

-

- For more information:

Please keep us informed of any stomach bug or norovirus cases by sending an email to stomachbug@appalachiantrail.org with the date and location of the outbreak.

Other diseases transmitted by animals

Some critters on the A.T. are capable of transmitting disease. Learn about these diseases and how to minimize your risk before setting off on your hike!

Rabies

Cases of rabies have been reported in foxes, raccoons, and other small animals.

Bats can carry rabies and bites from bats may be so small that you may not notice the bite when you are sleeping.

Although instances of hikers being bitten by rabid animals are rare, any animal bite is a serious concern. If you are bitten by an animal, wash the wound thoroughly with soap and water and seek medical assistance.

More information is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS)

One case of the rare but dangerous rodent-borne disease hantavirus pulmonary syndrome has been reported on the Trail. In 1993, an A.T. thru-hiker contracted hantavirus as he hiked through Virginia. He recovered and completed his hike the next year. Investigators were unable to pinpoint the exact location of infection.

Precautionary measures to avoid exposure to HPS:

- Air out a closed, mice-infested structure for an hour before occupying it.

- Avoid sleeping on mouse droppings (use a mat or tent) or handling mice.

- Treat your water, and wash hands.

- More information is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Park Service Public Health Program.

COVID-19

Help prevent spreading COVID-19 on the A.T. and other illness by following these guidelines:

Do:

- Leave the A.T. if you experience COVID-19 symptoms.

- Wear a mask when near others if you are experiencing COVID-19 symptoms.

- Cover your mouth when coughing or sneezing.

- Stay 6 feet from others if you are experiencing COVID-19 symptoms.

- Clean your hands regularly with soap and water (at least 200 feet from water sources).

- If you are experiencing COVID-19 symptoms, tent and use a bear canister instead of staying in shelters and using shared food storage devices.

- Be respectful of individual business masking protocols during A.T. community visits.

Don’t:

- Visit the A.T. when experiencing symptoms of COVID-19.

- Share gear or food.

- Touch your eyes, mouth or nose without washing your hands.

Discover More

Plan and Prepare

Hiker Resource Library

A collection of resources for hikers to stay safe, healthy, and responsible on the Appalachian Trail.

COVID-19 Hiking Tips

Staying Safe on the A.T.

Health and safety guidelines for A.T. hikers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

BY CAITLIN MILLER

11 Easy Ways to Improve Your Leave No Trace Footprint

A collection of simple and seemingly small ways you can practice Leave No Trace and help protect the A.T. experience.