Learn More

Standing Tall

“At one time I had understood as well as anyone why land trusts and conservancies need to protect the spirit of cooperation, need to keep a low profile in the face of charges of elitism and misplaced accusations of intrusions on the property rights of old-timers, or even mine owners. To fulfill their mission they buy land, and to buy land you have to be able to develop relationships based on trust. They do not shy from the big policy battles, and they enter regional and statewide debates on funding and legislation, but a Dog Town brawl having to do with acoustic and visual impacts originating on private property was a different matter altogether. But in the fight I saw coming, there was no room for collaboration. No trust. There was only us vs. them. Me vs. Charles. Ollie vs. Paul. Saving the mountain or tearing it down.”

“At one time I had understood as well as anyone why land trusts and conservancies need to protect the spirit of cooperation, need to keep a low profile in the face of charges of elitism and misplaced accusations of intrusions on the property rights of old-timers, or even mine owners. To fulfill their mission they buy land, and to buy land you have to be able to develop relationships based on trust. They do not shy from the big policy battles, and they enter regional and statewide debates on funding and legislation, but a Dog Town brawl having to do with acoustic and visual impacts originating on private property was a different matter altogether. But in the fight I saw coming, there was no room for collaboration. No trust. There was only us vs. them. Me vs. Charles. Ollie vs. Paul. Saving the mountain or tearing it down.”

Jay Erskine Leutze

Stand Up That Mountain

“David and Goliath” stories are well-worn territory in Hollywood. Every year there is a film about the underdog basketball team that fights their way to the finals and defeats their well-trained rivals; or about the down-on-his-luck detective breaking a case that exposes an entire criminal operation; or about a ragtag group of rebels who strike a crushing blow against a seemingly-unstoppable army. These stories remind us that, if enough effort is devoted to a truly worthwhile goal, even the powerless can overthrow the powerful. Good conquers evil, the celebration begins, credits roll.

Rarely do things seem this simple in real life, where shades of gray border any issue that may initially seem black-and-white. In his acclaimed nonfiction Stand Up That Mountain, Jay Leutze discusses why Paul Brown’s granite mining operation on Belview Mountain might have initially seemed like a great idea:

“I had given it little thought, but crushed stone is central to much of what we do in modern society. It is spun into asphalt for road improvements, it is used in ditching, erosion control, and parking lot construction . . . It all starts with a quarry dug out of the ground, and without it life as we know it would grind to a swift, muddy halt.”

“I had given it little thought, but crushed stone is central to much of what we do in modern society. It is spun into asphalt for road improvements, it is used in ditching, erosion control, and parking lot construction . . . It all starts with a quarry dug out of the ground, and without it life as we know it would grind to a swift, muddy halt.”

For some, looking at Belview Mountain was looking at a pile of untapped potential, a source of stone that would greatly benefit Brown’s company and its backers. Turning this mountain into a pile of rubble, and then selling that rubble to build roads and buildings, was an absolute no-brainer. Many were so convinced by the benefits of this project (including the financial gain it would bring) that they were willing to do almost anything — such as ignoring the law and preventing those who might speak against the project from being able to raise their voice — to make it happen.

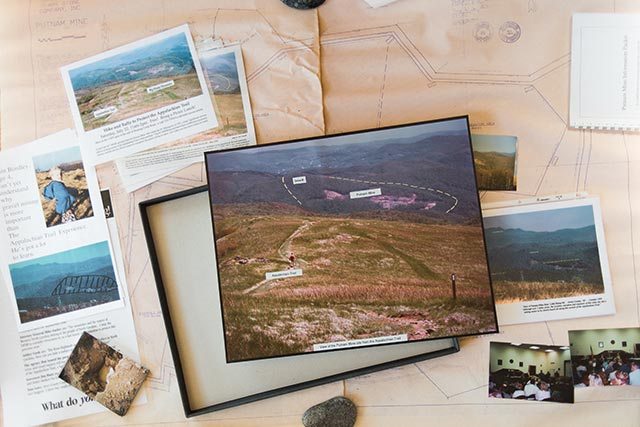

However, in the speedy pursuit of what might be gained by an unimpeded pursuit of profit — monetary or otherwise — we all-too-often overlook what may be destroyed in the process. The destruction of Belview would have also been the destruction of the irreplaceable views from the Appalachian Trail (A.T.) in the Roan Highlands. It would have been the destruction of the silence and solitude of the mountains that millions actively pursue each year, instead replaced with the constant churning of rock, the rumble of heavy-duty excavation equipment, and the deafening explosions of dynamite. It would have been the destruction of a way of life for “mountain people” like Ollie Cox, Ashley Cook, and so many others whose heritage rested on the rounded summits and time-worn valleys of the Southern Appalachians.

Perhaps worst of all, it would have contributed to the destruction of the idea that, no matter what the economical benefit may be, some places deserve to be preserved and protected from the ever-growing societal pressure to be valued only in terms of dollars.

The mountain people of Avery County, outdoor enthusiasts, and A.T. lovers across the country knew exactly what was at stake: not just a pristine view of undisturbed Appalachian mountainsides for close to 100 miles, but also the sense that any place previously thought as untouchable, as heritage — as home — could still be taken from them by the highest bidder.

“In legal terms, Paul Brown’s crusher might as well have been going in next to Yellowstone, or Yosemite,” Leutze said in regards to the proximity of the Putnam Gravel Mine to the A.T., the fact that ultimately led to the protection of Belview Mountain and its surrounding lands. However, it took years of legal work, bureaucratic maneuvering, and, most importantly, constant pressure from tens of thousands of individuals to ensure that these lands were protected.

This has become the norm in conservation issues as more and more dollars are funneled toward lessening the protection of lands and the experiences that define them in favor of development projects.

Jay Leutze In Lodge

Currently, the Trail and many small towns throughout Virginia and West Virginia are experiencing a similar plight in the form of modern energy infrastructure development, most notably the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Many of the threats this project imposes are eerily similar to those experienced by the people surrounding Belview Mountain, including decreased water safety, loss in property values and tourism dollars, and the destruction of mountain views that have represented their heritage for centuries.

Yet successes like that of Leutze and the rest of the “Dog Town Bunch” prove that these projects are not the unstoppable Goliaths that these companies so often appear to be. Through the support of thousands of dedicated A.T. lovers and citizens, as well as many other partners throughout the conservation community, we will place continual pressure on elected officials and other key players to remind them that these places are not just holding grounds for future developments. Rather, the A.T. and its kin are refuges from the signs of progress that increasingly surround us, an escape into the simple-yet-transformative beauty that nature seems to effortlessly provide just by existing.

When Jay Leutze looks at Belview Mountain, he sees the faces of Ollie Cox, Ashley Cook, and the thousands of individuals who stood their ground against a seemingly unstoppable force. When I look at the A.T., I see a similar reflection of the thousands of volunteers, members, and donors who realize that the Trail and the surrounding mountains are not untapped potential, but rather the result of a society that understands the value of a walk on an Appalachian ridge.

– by Jordan Bowman, Public Relations and Social Media Specialist at the Appalachian Trail Conservancy