by Brian King, ATC Publisher

The Last 2 Miles

August 14, 2018

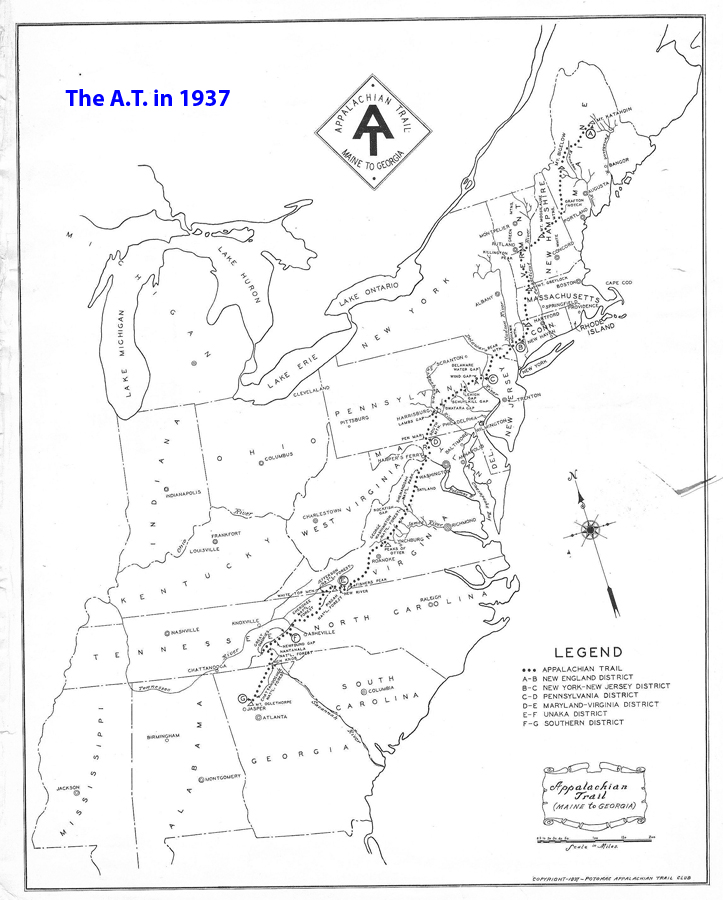

A continuous Appalachian Trail from Maine to Georgia should have been pronounced open, under ATC Chairman Myron H. Avery’s schedule, in 1936. By that time, he had walked and measured every step of the scouted or constructed route and become the first “2,000 miler” on the footpath.

One mile remained between Davenport Gap and the Big Pigeon River in Tennessee, and two miles had to be built 186 miles south of Katahdin, on a high ridge connecting Spaulding and Sugarloaf mountains in Maine.

One mile remained between Davenport Gap and the Big Pigeon River in Tennessee, and two miles had to be built 186 miles south of Katahdin, on a high ridge connecting Spaulding and Sugarloaf mountains in Maine.

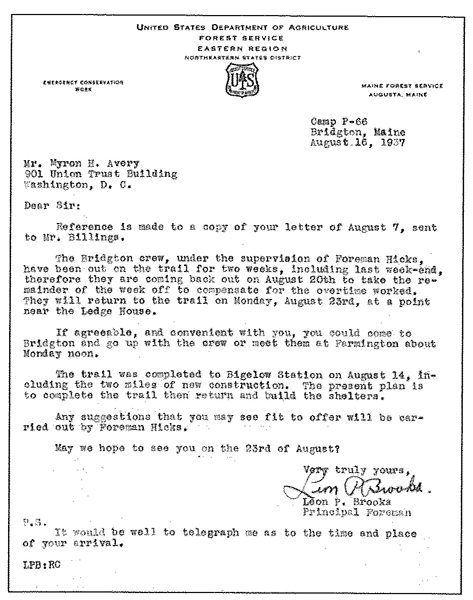

A late-summer snowstorm prevented completion of the Maine work in 1936. With the southern gap in the 2,025-mile route taken care of early the next spring, a six-man Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) “Bridgton crew” completed the final link in the Maine woods, without fanfare, on August 14, 1937. Leon P. Brooks, the principal U.S. Forest Service foreman in Maine, advised Avery by letter two days later: “The trail was completed to Bigelow Station on August 14, including the two miles of new construction.”

That section is now a side trail off the main trunk of the A.T., and one member of that CCC crew lived to join in 1987 50th-anniversary commemoration ceremonies there.

What is often overlooked in Trail histories but obvious in the story of this last leg of the original footpath is that it was not an all-volunteer effort, although volunteers were the driving force. Avery and other volunteers early on only had time to scout, flag, and often blaze the route, maintaining it across private lands, but crews in national forest and parks and Depression-era federal and state entities primarily handled trail construction and maintenance on public lands within their jurisdictions.

Two months earlier, Avery had quietly saluted the imminent completion of the Trail-construction era — saluting the Southern “conquerors” for beating his alliance in his home state of Maine — but immediately challenged ATC members, meeting in Gatlinburg, Tennessee:

Rather than a sense of exultation, this situation brings a fuller realization of our responsibilities. To say that the Trail is completed would be a complete misnomer. Those of us, who have physically worked on the Trail, know that the Trail, as such, will never be completed. As long as the project exists, there will be ever present, in increasing seriousness, the problems of maintenance and of developing a greater utilization of the Trail’s attractions. On this score, the Appalachian Trail will always be unfinished.

Although Trail-building had been nominally completed after fifteen years, Avery and his allies before the meeting was over would set the Conference on its next major course, which would dominate the Trail story for more than the next sixty.

They knew the fragility of that first route across the lands of amenable private owners in Maine and across the mid-Atlantic from New York to central Virginia. Even the public lands it crossed were subject to sudden political decisions to favor a jobs-producing road or highway instead, and even those old carriage roads were inevitably going to become automobile byways.

The era of seeking federal protection of the footpath and acquisition of lands — to become public lands — to buffer it had begun.

—Adapted from The Appalachian Trail: Celebrating America’s Hiking Trail

Copyright 2018, Appalachian Trail Conservancy