By Caitlin Miller, ATC Information Services Manager

It’s a Dirty Job: Partnering for Privy Construction

March 11, 2022

The Replacement of Moose Mountain Privy in 2021 Provides a Study in Cooperative Trail Management

Save for tales of a few urgent experiences, many Appalachian Trail (A.T.) hikers often overlook some of the most important structures on the entire footpath: privies.

Privies don’t just provide a convenient place to answer nature’s call: they are a critical part of Trail infrastructure that protects the surrounding landscape and other visitors from raw sewage. Many places along the A.T. see so much use that there is simply not enough space for even the best-dug cat holes to work effectively, or for visitors to find unused space (or because soils are shallow/water tables are high). Concentrating human waste in one place helps prevent the area around shelters and campsites from turning into a giant camper litterbox.

Yet as with most structures along the A.T., continual maintenance and, occasionally, a complete replacement is essential to ensure the privies are functioning properly. This was the case with the Moose Mountain Privy in New Hampshire (NOBO mile 1,763.1). Originally built in 2003, this privy was showing its age after 17 years of use: the floor was beginning to deteriorate, the base logs were rotting, and the seat was broken. More importantly, the single crib* it was built on for containing human waste was full, defeating the purpose of a moldering privy (and leading to the litterbox scenario described above). The old Moose Mountain privy was also built in an “open-air” style, meaning it had no walls. Hikers shared their visit to the privy with the wind, rain, and whoever happened to be around.

After five years of planning and coordination, Moose Mountain Privy was replaced by the Dartmouth Outing Club (DOC) in 2021. The process for completing this single, essential project helps highlight what it takes to maintain a 2,190-mile footpath and how the Trail’s unique Cooperative Management System works on the ground.

What are the different types of privies?

Just like the hundreds of shelters along the Trail, not all privies are built the same. Over the years, Trail maintainers have devised different privy models to compost waste in the backcountry and keep up with increasing use.

Pit Privies

Pit privies are the simplest and oldest privy design and are a large hole in the ground with a seat overtop.

Pros:

• Require little maintenance until the pit is full.

• Simplest design.

Cons:

• Human waste goes right into the soil.

• Full pits can take decades to fully decompose.

• Once full, the entire privy structure must be moved to a new hole, creating a larger impact.

• It takes a crew of at least four people to move a pit privy — they are heavy.

Moldering Privies

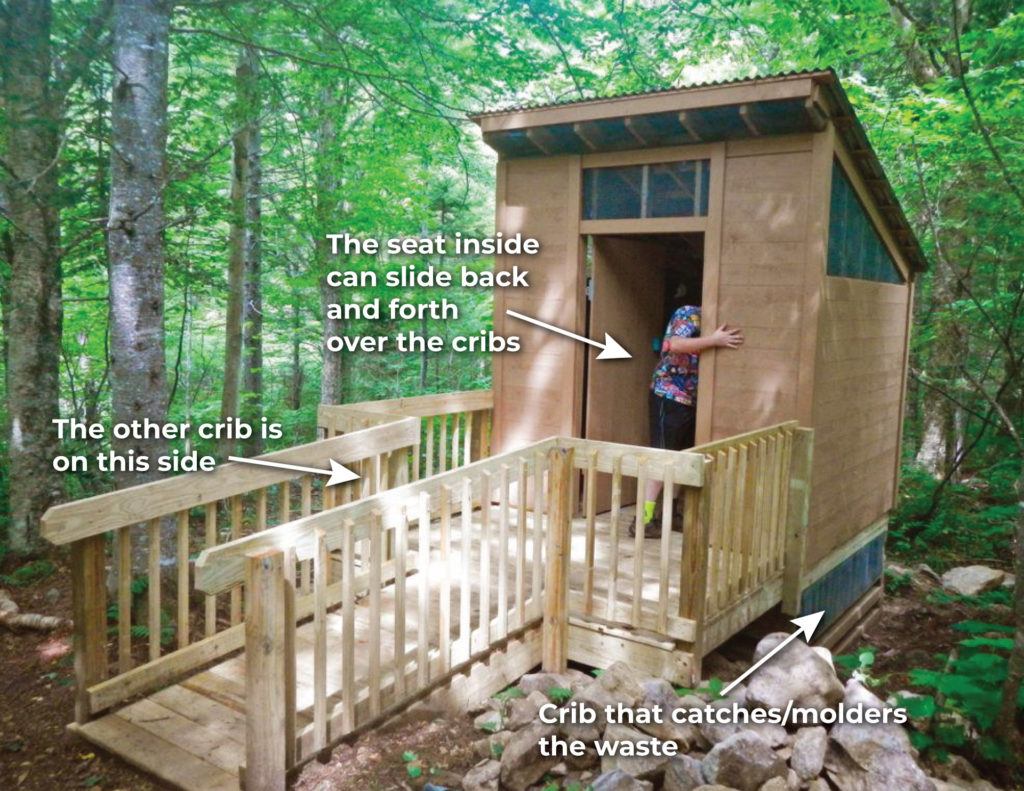

Moldering privies sit atop two or three above-ground cribs that catch waste. *Cribs provide the base of the privy and are large, slatted wooden boxes that the seat sits on and into which the poop goes. The cribs are often lined with chicken wire or hardware cloth to keep critters out while allowing the airflow needed for the waste to decompose.

Once finished, hikers throw in wood shavings or leaf litter to help speed up decomposition. Once the active crib is full, the seat is moved over an empty crib and the full crib is allowed to decompose or “molder.” The contents of the full crib take one or two hiking seasons to molder, composting the waste and reducing in volume. The seat can then be moved back and forth between the cribs as they fill. This allows maintainers to have access to the cribs to turn the waste, add wood shavings, etc. And is much easier than moving the entire structure to a new site.

Pros:

• Compost waste more efficiently than pit privies.

• Keep waste above ground, which lowers the risk of groundwater contamination.

• Relatively easy to slide the seat back and forth from the active to moldering crib.

• Smaller overall footprint than a pit privy.

Cons:

• More expensive to build than a pit privy

• Needs semi-regular maintenance, including resupplies of wood shavings.

• Might not be suitable for extremely popular sites where use may cause the cribs to fill faster than they can molder.

Batch Bin Composting Privies

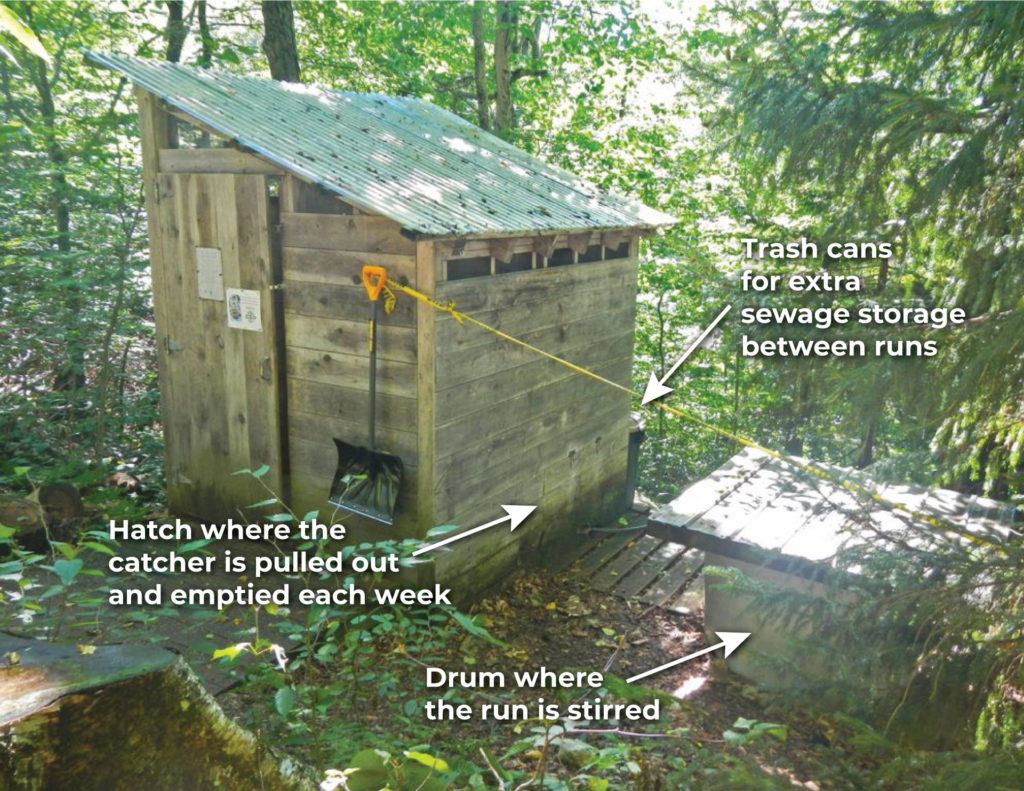

Batch Bin Composting privies sit, appropriately, atop a bin or “catcher.” Behind the privy sits a large drum where the raw sewage from the catcher is mixed with bark mulch into a composting “run.” Each run takes four to six weeks and is stirred weekly to speed up the composting process. Once a run is finished, the material is moved from the stirring drum to a drying rack, where it will stay for a year or two before being scattered nearby, packed out, or added to a new run.

Composting privies have a store of bark mulch for hikers to throw in between uses to soak up the excess moisture, which can slow the composting process. For this reason, composting privies will often have signs asking you not to pee in them.

Pros:

• Capable of composting large volumes in one season, making it suitable for high use sites.

• Keep raw sewage out of the ground. Once the final material has dried long enough, it should be rid of all pathogens and have the look and smell of topsoil.

Cons:

• More expensive to build than a pit privy.

• Require weekly maintenance during the hiking season.

• Require packing in bark mulch or airlifting by helicopter.

No matter the type of privy, none of them compost trash including feminine hygiene products, biodegradable wipes, food wrappers, socks, etc. In the case of moldering and composting privies, volunteers and ridgerunners are left with the dirty job of packing out privy trash that’s been through the composting process — it’s as gross as it sounds, so always pack out your trash.

Who Maintains and Replaces Privies?

Many privies are maintained through the hard work of dedicated volunteers (particularly the work of packing in bark mulch or collecting leaf litter), sweeping out privies, and “knocking the cone” — flattening waste that naturally tends to mound in the center. Privies that require more frequent attention like batch-bin composters tend to be maintained by paid staff who are trained to handle raw sewage and properly stir runs. Because of this, batch-bin composters are largely found along the northern section of the Trail. (Note: don’t touch any shovels or pitchforks you may see near a privy — those are used for stirring the runs.)

Behind the Scenes: Moose Mountain Privy

Replacing a privy is a huge undertaking that requires planning, funding, and collaboration. Once a privy is flagged by a Trail Club for replacement, the Club then works with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) and land manager to review the project. While the level of ATC involvement varies from Club to Club, this collaborative step is important to ensure that the project will meet requirements such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), and local management plans.

After flagging the Moose Mountain privy for replacement, the DOC submitted the project to the ATC for funding in 2017. For many Trail projects completed by Trail Clubs, the ATC acts as a pass-through for the funding process: the ATC receives funding from the National Park Service (NPS), private donors, and other sources in large chunks, which are then split up and passed to Trail Clubs. The pass-through funding model allows ATC to handle most of the administrative requirements that Trail Clubs might not be equipped to navigate on their own.

Once the funding was secured, the DOC, the ATC, and White Mountain National Forest (the land managing agency for most of the New Hampshire section of the Trail) worked together to finalize the rebuild plans. The funding for the Moose Mountain privy covered the cost of supplies and paid for the DOC trail crew that completed the project. The DOC trail crews are full-time, season-long paid crews that perform large-scale trail rehabilitation projects while providing professional development for students and future Trail stewards. The DOC has been maintaining its the 50-mile stretch of the A.T. between Hanover, New Hampshire, and Kinsman Notch since the Trail was laid out in that area, and has fostered many generations of Trail maintainers. This project was a great fit for their paid crew and in 2021 they constructed a beautiful new, double-crib molderer — this time complete with walls!

Beyond Moose Mountain Privy

I love talking about privies because, as the Moose Mountain privy rebuild illustrates, they are perfect examples of how much work happens behind the scenes to preserve the A.T. As the number of visitors to the Trail continues to rise, Trail maintainers will continue working hard to keep up with use and working together to protect the A.T. experience.

And you can help — regardless of the type, all privies rely on responsible use to function properly. Be sure to read the signs in privies, follow the instructions, pack out your trash, and treat each visit as an opportunity to contribute to an important but often overlooked part of maintaining the Trail.

Interested in taking a deeper (metaphorical) dive into backcountry privies? Check out the Backcountry Sanitation Manual.

Information about the Moose Mountain privy rebuild provided by Ilana Copel, New England Regional Office Administrator and Outreach Coordinator. The Dartmouth Outing Club Trail Crew program is coordinated by Willow Nilsen.

Discover More

Official Blog

An Act of Love

Love for a place, such as Max Patch on the Appalachian Trail, can have many origins. It can also manifest in the care we return to those cherished places.

Official Blog

Campsite Selection: The Secret to Happy Campers

Preparing your camping and sleeping setup is super important for maximizing your enjoyment and safety, and for reducing your impacts to the Appalachian Trail.

Take a walk with the ATC's official blog!

A.T. Footpath

Learn more about our work and the community of doers and dreamers that help protect and celebrate the A.T.