By Jordan Bowman, ATC Director of Communications

Where the Appalachian Trail Began

May 26, 2021

“Life for two weeks on the mountain top would show up many things about life during the other fifty weeks down below… There would be a chance to catch a breath, to study the dynamic forces of nature and the possibilities of shifting to them the burdens now carried on the backs of men.”

-Benton MacKaye

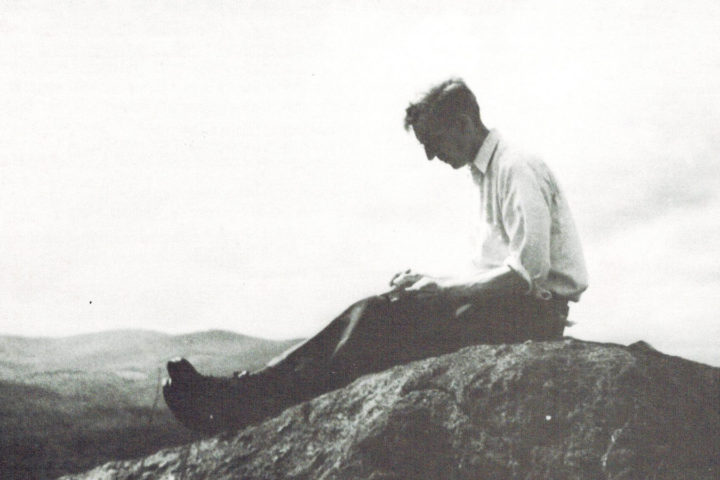

Long before Benton MacKaye wrote his landmark 1921 article, “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning” — the article that sparked the imagination of thousands and led to the construction of the A.T. — the idea for the Trail came to him in the most appropriate way possible.

The year was 1900 and, in the rolling Green Mountains of Vermont, MacKaye laced up his boots and began to hike.

A new century had begun, and the Second Industrial Revolution had transformed America. The population was booming, growing by more than 20 percent in just ten years. The expansion of factories increased the production of essential materials such as steel and provided millions of jobs, the majority focused in cities sprawling wider each year. Thousands of miles of railroads crisscrossed the nation, allowing for easier travel and material transportation and further expansion out West, eventually bringing an end to the American frontier. On the East Coast, the pace of industrialization seemed unstoppable, and the reach of urbanization began to stretch into the Appalachian Mountain range.

MacKaye had recently graduated from Harvard University and, along with a friend, set out to bushwhack through the thick Vermont backwoods. After traipsing over glacier-scraped rock and through the seemingly never-ending forests, MacKaye found himself at the peak of Stratton Mountain. There was no view from the summit, so MacKaye climbed a tree until he found one.

Even though he was already a seasoned outdoorsman who spent years of his life surveying the backwoods of New England, MacKaye was in awe of the beauty surrounding him, and a thought occurred to him that would change history.

“I felt as if atop the world, with a sort of ‘planetary feeling.’ … Would a footpath someday reach [far-southern peaks] from where I was then perched?”

In that moment, the idea for the A.T. was born.

It was another 21 years before MacKaye’s idea was revealed to the world. But from the spark of that idea — could such a trail even exist? — MacKaye began to understand the need for the Trail beyond recreation. Amid the turmoil brought about by a rapidly changing world and the long hours and dangerous conditions inherent to many of the era’s factory jobs, MacKaye was convinced that spending time in nature would provide the relief — or as he framed it, the “optimism” — needed to meet life’s challenges.

“First there would be the ‘oxygen’ that makes for a sensible optimism,” he wrote. “Two weeks spent in the real open — right now, this year and next — would be a little real living for thousands of people which they would be sure of getting before they died.”

To MacKaye, the A.T. was the solution. By providing an access point to nature within reach of America’s most dense population areas, from Boston to Atlanta, millions would be given a way to easily find the optimism only provided by nature.

Yet even then, MacKaye knew that much more than a footpath was needed — conserving the natural beauty of the lands around the Trail was essential for ensuring this natural experience would remain for the benefit of future generations.

“The Appalachian Trail indeed is conceived as the backbone of a super reservation and primeval recreation ground covering the length (and width) of the Appalachian Range itself, its ultimate purpose being to extend acquaintance with the scenery and serve as a guide to the understanding of nature.”

It is this wider goal — conserving the broader A.T. landscape so its natural beauty will continue to benefit us all — that guides the work of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) today.

Over the next several weeks, we will be exploring ideas about the natural beauty of the A.T. and its surrounding landscape, our continuing efforts to conserve these essential aspects of the A.T. experience, and the lasting impact MacKaye’s words have had in ensuring the Trail provides the optimism we need for future generations.

Through the work of the ATC and its partners (and your invaluable support), we will fulfill a goal as important today as it was more than a century ago — when a young Benton MacKaye, perched high in the Vermont treetops, understood the possibilities of a footpath following the ridgeline of the Appalachian Mountains.

Your donation supports our work to conserve the natural beauty of the Appalachian Trail, helping ensure its one-of-a-kind experience will benefit us all for generations to come.

Lead image by David Warners

Discover More

Official Blog

Preserving the “Oxygen” of the Trail

How Benton MacKaye’s call for protecting the “oxygen in the mountain air along the Appalachian skyline” guides our work in combating climate change on the A.T.

By Benton MacKaye

“An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning”

Originally published in October 1921, Benton MacKaye's article establishing the idea for the A.T. still inspires and guides the ATC's efforts today.

A.T. Footpath

Continuing the A.T. Vision

Even after 100 years, Benton MacKaye’s 1921 vision for the Appalachian Trail continues to guide the ATC in its mission.